| ||||||||||||||||||||

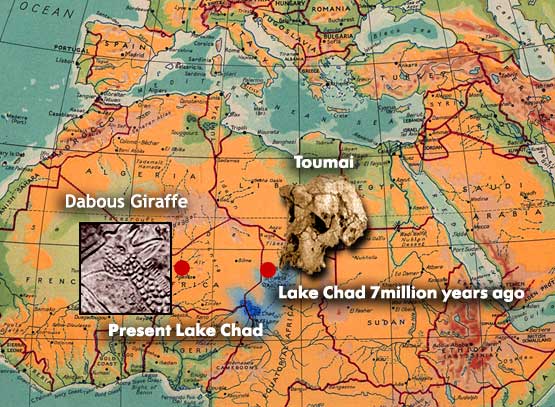

| A skull discovered in the deserts of Central Africa belongs to our earliest known human ancestor. Our scientists hope that it will supply a missing link in evolution. The fossil, unearthed in Chad, is between six and seven million years old, pushing back the roots of the human family tree by up to one million years, shedding light on mankind's divergence from chimpanzees. The specimen, a new species of archaic human being, or hominid, has been nicknamed Toumai, a local name meaning "hope of life", which is normally given to children born shortly before the dry season. Its scientific name is Sahelanthropus tchadensis, after the Sahel region and the country in which it was found. Toumai is the most important fossil discovery to date, rivalling the discovery of the first 'ape-man', Australopithecus africanus, which founded the science of paleoanthropology. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| The find is significant because it falls in the "fossil gap", the time between the common ancestor of modern apes and human beings, about nine million years ago, and the first hominid remains of between four and six million years ago. The entire record of primate evolution during this crucial era, in which the human and chimpanzee branches of evolution divided, is minimal. It has generally been thought that the last common ancestor of both human beings and chimpanzees lived between about six and seven million years ago, but Toumai's date suggests that the evolutionary divide must in fact have happened much earlier. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| The fossil is up to a million years older than the earliest previously known hominids, Orrorin tugenensis, or Millennium Man, which lived six million years ago in Kenya, and Ardipithecus ramidus kaddaba, an Ethiopian specimen dated to between 5.2 and 5.8 million years ago. The skull is three million years older than the next earliest, and indicates that early hominids were widespread throughout Africa. The vast majority of previous finds have been in the East or South of the continent. Dr Michel Brunet, of the University of Poitiers in France, who led the research team, said; "This is the oldest hominid. It's seven million years old, so the divergence between chimp and human must be even older than we thought before. Here we are not far from the divergence between chimp and human". Toumai, who was almost certainly male, had a brain about the size of a modem chimpanzee and could have walked on two legs in an upright posture, according to analysis of the point at which his spine joined his skull. The find consists of an intact skull, two fragments of jawbone and 3 teeth from 5 individuals. No parts of the lower skeleton have been found, making it impossible to reconstruct how he would have looked or walked. Several of Toumai's characteristics mark him out as a hominid rather than an ape: particularly short canine teeth and a thick and continuous brow ridge. The latter feature even suggests that he may be a direct ancestor of modern man, Homo sapiens, rather than just a relative: it is only seen elsewhere in the genus Homo, and not in other types of ape-men. If this is correct it will particularly please Australia's Dr. Alan Thorne who has advanced the Regional Continuity theory against the generally accepted Out of Africa theory. Toumai has proved to be a greater prize, and the find is already starting to recast standard ideas about the distribution of the first hominids. Although the region where he was found is now desert, Toumai's habitat would have been very different. Evidence from other animal fossils in the same rock strata show that it would have been wooded grassland or savannah in a belt between a large Lake Chad and the Sahara Desert to the north. Fossils belonging to 42 vertebrate species have been unearthed close to Toumai's remains, including primitive versions of elephants, giraffes, horses, rodents and monkeys. It is these specimens that have provided scientists with Toumai's date. Local rock sediments cannot be dated using radioactive isotopes, the standard method, because there are no layers of volcanic ash, which normally provide the necessary argon and potassium. Instead, the researchers have dated the hominid by reference to the evolutionary level of the other fossils that were laid down at the same date. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| | ||||||||||||||||||||