Rock art theories V

|

Rock art theories: a brief overview of the salient theories concerning Palaeolithic rock art in Europe and around the world.

Shamanism

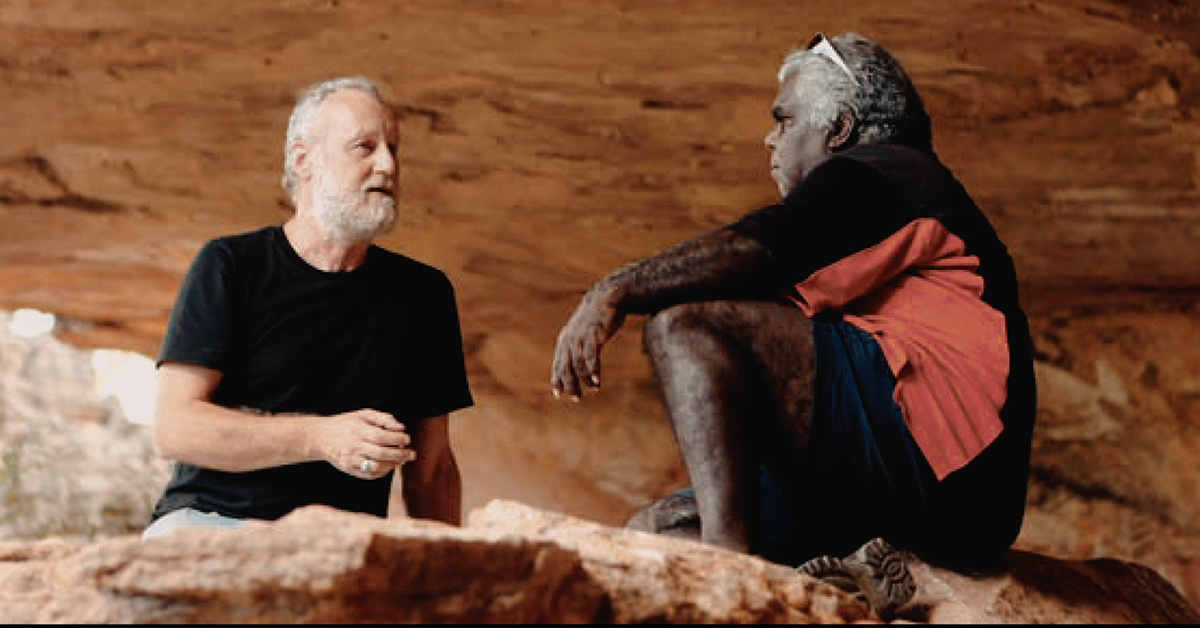

In a hunter-gatherer society, the shaman was a very important figure; priest, magician, healer, artist. As a messenger, medium or emissary, the shaman's role was to make the 'extraordinary' ordinary. The shaman could liaise between this world - the natural world - and the spirit world.

It has been argued that in hunter-gatherer societies, the rock face itself was believed to be the interface - the veil - between these two worlds. However, the worlds themselves were not separate entities; the shaman would derive the life-force from the animals in the spirit world, and redirect that life-force onto the people in the natural world. This theory of rock art proposes that Palaeolithic images are spirit animals not real animals, and the composite figures represent shamans or sorcerers with masks.

This is described in 'The Shamans of Prehistory: Trance & Magic in the Painted Caves' by Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams:

When travellers from western Europe began to explore distant parts of the world, they encountered religious beliefs and practices that were, for them, strange, bizarre and sometimes terrifying. The explorers came from a social and intellectual background that was in large measure determined by strict religious dogma, and their confidence in the truth of their own religious beliefs led them to regard the beliefs of others as degenerate, evil and satanic.

Marco Polo for instance, together with subsequent generations of travellers in Siberia, found religious practitioners who donned elaborately decorated garments, including, sometimes, towering antlers. Thus attired, they danced and beat drums until they entered a frenzy. In this 'wild' state, so the explorers were informed, they foretold the future, and conversed with spirits and spirit animals.

The term shaman is now used in western languages applied to similar ritual specialists around the world who go into a trance - frenzied or passive - to heal the sick, change the weather, foretell the future, control the movements of animals and converse with spirits and spirit-animals.

The shamans journey to the spirit realm varied - protracted dancing and hyperventilation, the consumption of intoxicating beverages - but in the widely separated regions of Siberia, the Americas and southern Africa, these particular people, by various means, went into a state of ecstacy. Virtually without exception, early western explorers considered this sort of behaviour highly distasteful and primitive. There is a great irony here; ecstatic revelations and visions are also an integral part of the Judeo-Christian tradition that stretches back to Old Testament times. It can be argued that the tradition still goes further back, even to the first emergence of fully modern human beings. At all times and in all places people have entered ecstatic or frenzied altered states of consciousness and experienced hallucinations. The big jump that came with Homo Sapiens was the awareness of being. Then different levels of being, in other words, different states of consciousness - from alert consciousness to deep trance.

In pre-Columbian America, Algonquians - the tribes who occupied land from what is now known as North Carolina and Virginia up to Newfoundland - viewed the natural world and the spirit world as one entity; a concept known as 'manitou'. Edward J. Lenik describes how spirits and places of spiritual power were associated with special topographical features. The people were intimately connected with the landscape. A major component of Manitou was the vision quest, sought by all individuals. This trance-like state was achieved on perhaps a greater and more frequent scale by the shaman, or medicine man, for the sake of healing, predicting, altering phenomena, and receiving spiritual power. Rock art was the result of this contact with the spirits. The rock art recorded the success of that contact.

In Palaeolithic Europe, the themes depicted in the rock art suggest that the paintings were not the expression of material, utilitarian or purely artistic preoccupations. Instead, the symbols and the animals represented expressions of a spiritual conception of existence. In Lascaux, the 'shaft scene' (above) may depict a shamanic interaction between the bird-headed man, the bird on a stick and the animal spirit of the wounded bison. The geometric symbols found in rock art are interpretted as phosphene forms; subconscious images and shapes in the neural system and visual cortex of human beings.

The fact that these paintings and engravings were made deep inside caves where nobody lived suggests they were endowed with spiritual significance. At this time, Palaeolithic humankind was surrounded by animals, and therefore part of this faunal matrix, not above it. Passing through the veil, the spirit animals appear to emerge from the rock face (below). Animals appear to float in space, as the lines of the ground are never depicted. Within the caves, images of all periods make use of natural features of the rock - cracks, hollows, bulges and ledges are incorporated into the images. The caves themselves were important; our Palaeolithic ancestors may have been believed that they represented the lower tier of the shamanic cosmos.

Not all palaeolithic rock art can be ascribed to shamanic practices, but this concept does help us take a step toward understanding our ancestors' attitude to the supernatural and their ways of approaching their own gods.

Critics of this theory question the value of it being based so heavily on ethnographic accounts. And whilst accepting shamanism within hunter-gatherer societies, they ask how it relates to rock art; was it tied to art? Were the shamans the artists? Were they painting whilst in a trance? Ultimately, the critics feel that as a hypothesis it cannot be tested or falsified.

Visit the Book Review to read more about 'The Shamans of Prehistory: Trance & Magic in the Painted Caves' by Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams:

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/books/shamans_of_prehistory.php

COMMENTS |

|