Rock art theories: a brief overview of the salient theories concerning Palaeolithic rock art in Europe and around the world.

Acoustics

A relatively new approach to rock art involves the relation between sound and art.

Researchers, by focussing on acoustics, are finding correlations between the locations of decorations and the areas of resonance for voices or instruments. Areas of great resonance are often related to the depiction of horses; the sounds of herds of horses on the move. Alternatively, areas of low resonance are often related to the depiction of felines; the quiet stealth of cats.

Palaeolithic artists would certainly have noticed the acoustical properties of the caves, and they may have been influenced them in the choice of locations to paint, draw or engrave. Indeed, the locations may well have been chosen for ceremonial or ritual purposes due to the acoustics, and the art was secondary.

Researchers, such as Iegor Reznikoff, Michel Dauvois and Chris Scarre among others, have compared maps of the most resonant locations in caves with maps of the locations of the paintings. Correlations appear to be 'positive'; the more resonant the location, the more paintings or signs are situated in this location. Moreover, some researchers are exploring whether rock petroglyphs and megalithic structures, such as Stonehenge, may have been inspired by sound waves.

Just as light can be reflected, so too can sound, perhaps from a reflecting plane such as a large cliff face. This can result in an auditory illusion of somebody answering you from within the rock. This was certainly the case at the Huashan rock art sites in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in southern China; the symbols of drums depicted in the rock art were not accidental. Large bronze drums, intricately cast, would have been part of the prehistoric ceremony of the local ethnic culture, played from the land across the river towards the cliffs adorned with rock art. And in terms of great resonance, we have already looked at the stunning acoustics in the Salon Noir of Niaux cave in France in Rock art theories VI Observing not Interpreting.

The implication of this research, and of archaeoacoustics - the use of acoustical study as a methodological approach within archaeology - in general, is that it demonstrates that acoustical phenomena were culturally significant to prehistoric populations. Indeed, natural soundscapes of archaeological sites should be preserved for further study.

Sound was a primary focus for accumulating knowledge, culture and information in prehistory, as a great deal of transmission happened using language (the acoustic), rather than writing (the visual). Therefore we can expect to find as much out about a rock art site or a megalithic site by investigating its acoustic properties. This is perhaps especially the case in a site that does not seem to be designed for strictly functional purposes such as accommodation or defence, as music and sound are often to be found at the core of cultural, communal and ritual activities.

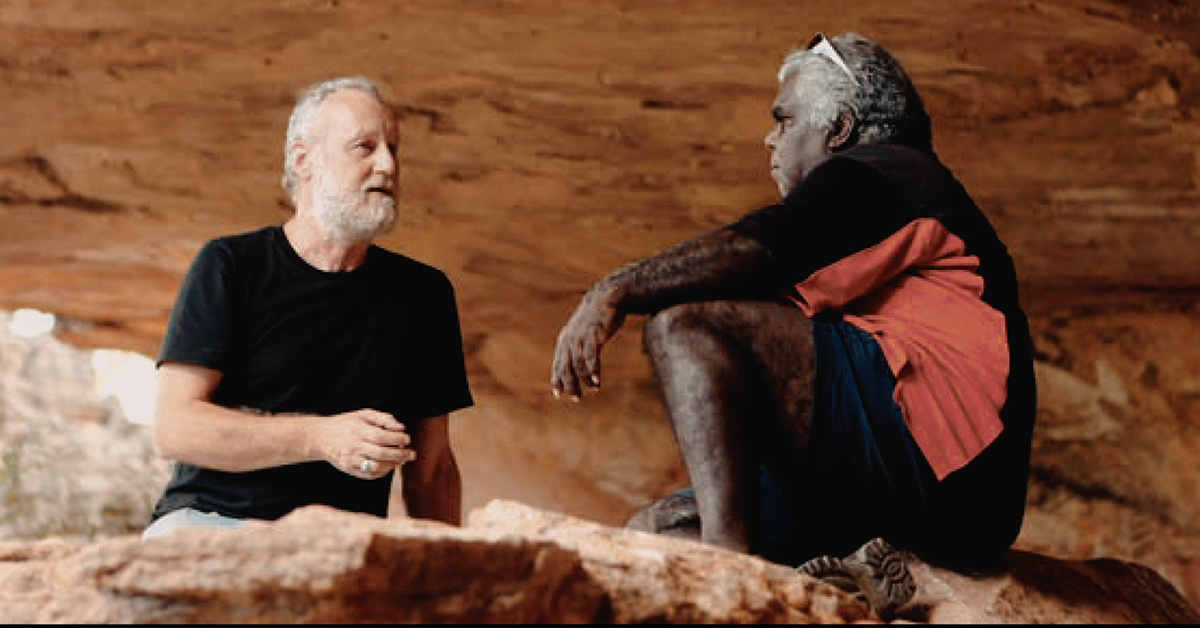

In 2014 Dr. Rupert Till, Director of the European Music Archaeology Project at the University of Huddersfield, and colleagues carried out the Songs of the Caves Research Project (pictured above). This aimed to explore the sounds of 5 caves that are part of the Cave of Altamira and Palaeolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain World Heritage Site. In the caves of La Garma, El Castillo, Las Chimineas, El Pasiega and Tito Bustillo the team explored the acoustics of the caves and their relationships with the cave art present. The art in the caves is up to 40,000 years old, and the team tested whether there was any evidence that sound played a part in where these visual motifs were placed. In addition various instruments were played and recorded in the caves, to demonstrate their acoustics and see what the caves might sound like with different sound sources. Many of the instruments were reconstructions of archaeological finds, including bone flutes which were made up to 30 or 40,000 years ago.

Results published soon.

The study of acoustics in relation to rock art, again in its infancy, may well go on to demonstrate the planning that occurred in prehistoric sites, which may in turn help the interpretation of the art.

Critics to this approach argue that Palaeolithic artists would have chosen nonporous rather than porous rocks to conserve pigment. Nonporous rocks are highly sound-reflective, and therefore highly resonant, whilst porous rocks absorb sound, and are therefore less resonant. This may mean that a highly decorated area of a cave did not necessarily reflect the artists' preference for resonance as opposed to a suitable canvas.

Read more at the Sounds of Stonehenge:

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/stonehenge/stonehenge_sounds/index.php

Comment

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 24 November 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 27 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 08 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 July 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 06 June 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 11 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 02 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 16 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 06 July 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 16 March 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 24 November 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 27 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 08 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 July 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 06 June 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 11 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 02 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 16 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 06 July 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 16 March 2021

Friend of the Foundation