by Chris Stringer

- Hardback: 352 pages

- Publisher: Allen Lane

- ISBN-10: 1846141400

- ISBN-13: 978-1846141409

- Dimensions: 23.6 x 16 x 3.6 cm

Review:

"If there has been no spiritual change of kind / Within our species since Cro-Magnon Man . . ." The poet Louis MacNeice was voicing a commonplace that was accepted by most experts on human evolution until very recently - in fact still is by some. The evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould put it like this: "There's been no biological change in humans in 40,000 or 50,000 years. Everything we call culture and civilisation we've built with the same body and brain."

The Cro-Magnons were the creators of the cave paintings at Lascaux and Altamira – the ice age hunter gatherers whose art astounds us ("We have learned nothing," said Picasso, after seeing Lascaux). They were modern humans who entered Europe only about 40,000 years ago, and there, despite the hostile ice age environment, created the first artistically sophisticated culture. But that wasn't the end of human evolution. Modern genomics has now shown us that biological evolution actually accelerated from this point on, especially since the beginning of farming 10,000 years ago.

The wealth of cross-referring evidence now available from fossils, archaeology and genomics has made the study of human evolution itself a rapidly evolving topic, and Chris Stringer is in the thick of this ferment. He is Britain's foremost expert on human evolution and, as a palaeontologist at the Natural History Museum, has been involved in much of the crucial research. This probably accounts for the fact that in writing this popular account he cannot altogether wrench himself away from the academic arena in which one authority is forever contesting the findings of another. Such wrangling is unfortunately necessary because if recorded history has, as Eliot wrote, "many cunning passages", that's as nothing compared to the waxing and waning of human fortunes, battling with ice ages and natural catastrophes over hundreds of thousands of years of evolution. And the evidence, of course, is indirect and has to be pieced together from analyses of mineralised fragments of the past.

Stringer is most concerned with the period from the emergence of Homo sapiens in Africa, around 195,000 years ago, to their arrival in Europe and the subsequent demise of the Neanderthals (who had left Africa hundreds of thousands of years before). The archaeological record shows Homo sapiens in Africa several times on the verge of a cultural breakthrough, but this is not consolidated until their arrival in Europe. Stringer writes: "It is as though the candle glow of modernity was intermittent, repeatedly flickering on and off again."

The introduction of farming, first in Iraq and Turkey, was the single greatest event in the evolution of Homo sapiens since its emergence. From farming flowed, in an incredibly short time, population growth, craft, art, religion and technology. New cultural practices led to radical genetic changes, the ability of northern Europeans to digest cow's milk being the most dramatic. This followed the adoption of cattle rearing and reverses the idea that genetic mutations have initiated innovation. Just as often, it seems, it has been culture that has led, genes that have followed.

Although new fossil and archaeological evidence continues to mount, the driving force in understanding human evolution today, as Chris Stringer emphasises, is genomic. It is now possible to compare the genomes of Neanderthals with modern humans and with chimpanzees. This work will go on for many years – the genome consists of 3bn letters, any one of which might mutate – but already dramatic results are emerging.

Stringer has been a strong advocate of the dominant Out-of-Africa theory that modern humans emerged from that continent and entirely replaced earlier human types such as Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis and the Neanderthals. But while Out-of-Africa still holds sway, the picture is losing some of its classical simplicity. Last year, the Neanderthal Genome Project, led by the Swedish biologist Svante Pääbo, finally established that modern humans in Europe and Asia (but not Africa) have some admixture of Neanderthal genes, thus ending decades of speculation. And in December last year the same team produced a total surprise: a genomic analysis of human remains from a cave in Denisova, southern Siberia, which proved to be genetically distinct from all known human types. The team declined at this stage to give the find a Linnean species name, but, by analogy with the Neanderthals, named it Denisovan after the location. The actual Denisovan specimens in Siberia were 30-50,000 years old, and the type predated both modern humans and Neanderthals.

Apart from having what is probably a new species to fit into the pattern of human evolution, the big shock of the Denisovans is that they also have contributed something to the modern human stock in Melanesia (the islands north of Australia that include Papua New Guinea). We now see a pattern emerging of interbreeding between modern humans and earlier types: Neanderthals in Europe and Asia and Denisovans in Melanesia. There will surely be further finds. Especially interesting is East Asia, first peopled by Homo erectus as long as 1.7m years ago.

Stringer's book does not quite live up to its magisterial title; the story is still too much in flux for that. But to follow the dramatic announcements that will be appearing in the media pretty regularly from now on concerning new fossil finds and detailed genetic knowledge on the mutations that distinguish us from Neanderthals, other hominins, and apes, you will need a primer to make sense of the story so far. Here is that book.

Chris Stringer:

Chris Stringer is one of the leading proponents of the recent single-origin hypothesis or 'Out of Africa' theory, which hypothesizes that modern humans originated in Africa over 100,000 years ago and replaced the world's archaic human species, such as Homo Erectus and Neanderthals, after migrating within and then out of Africa to the non-African world within the last 50,000 to 100,000 years.

He studied anthropology at University College London and holds a PhD in Anatomical Science, and a DSc in Anatomical Science both from Bristol University. He is a Research Leader in Human Origins at the Natural History Museum. He is director of the Ancient Human Occupation of Britain project. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Society. He won the 2008 Frink Medal of the Zoological Society of London.

→ Bradshaw Foundation - Book Review

→ Origins - Exploring the Fossil Record

by Kate Winter

13 November 2025 Book Review Archive

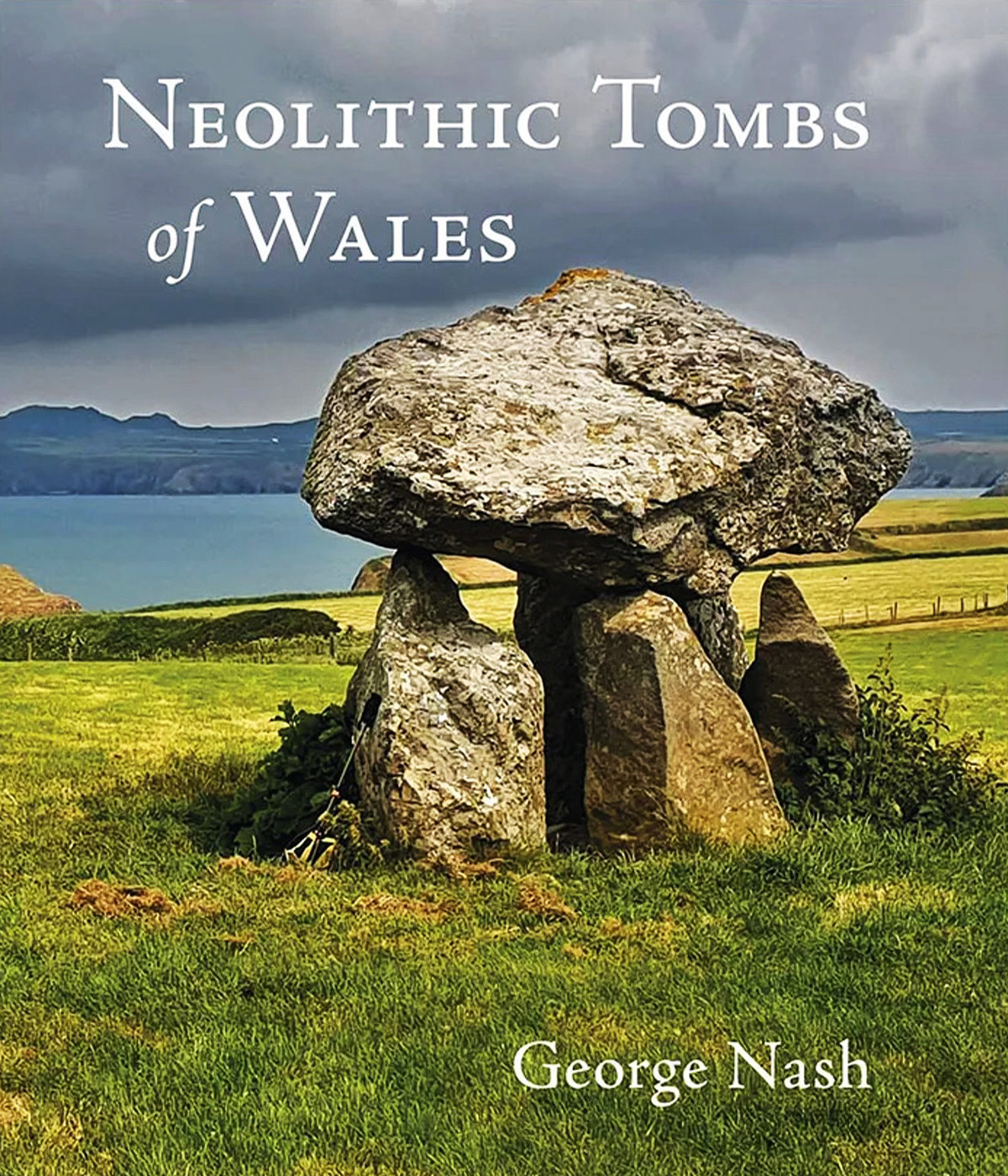

→ Neolithic Tombs of Wales

by George Nash

19 November 2024

by Simon Radchenko

22 May 2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak and Jean Clottes

10 November 2023

by Paola Demattè

12 January 2023

by Paul Pettitt

10 November 2022

by George Nash

19 November 2024

by Simon Radchenko

22 May 2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak and Jean Clottes

10 November 2023

by Paola Demattè

12 January 2023

by Paul Pettitt

10 November 2022

Friend of the Foundation

by George Nash

19 November 2024

by Simon Radchenko

22 May 2024

by Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak and Jean Clottes

10 November 2023

by Paola Demattè

12 January 2023

by Paul Pettitt

10 November 2022