Date of Construction: Between 2450 & 2350 BC

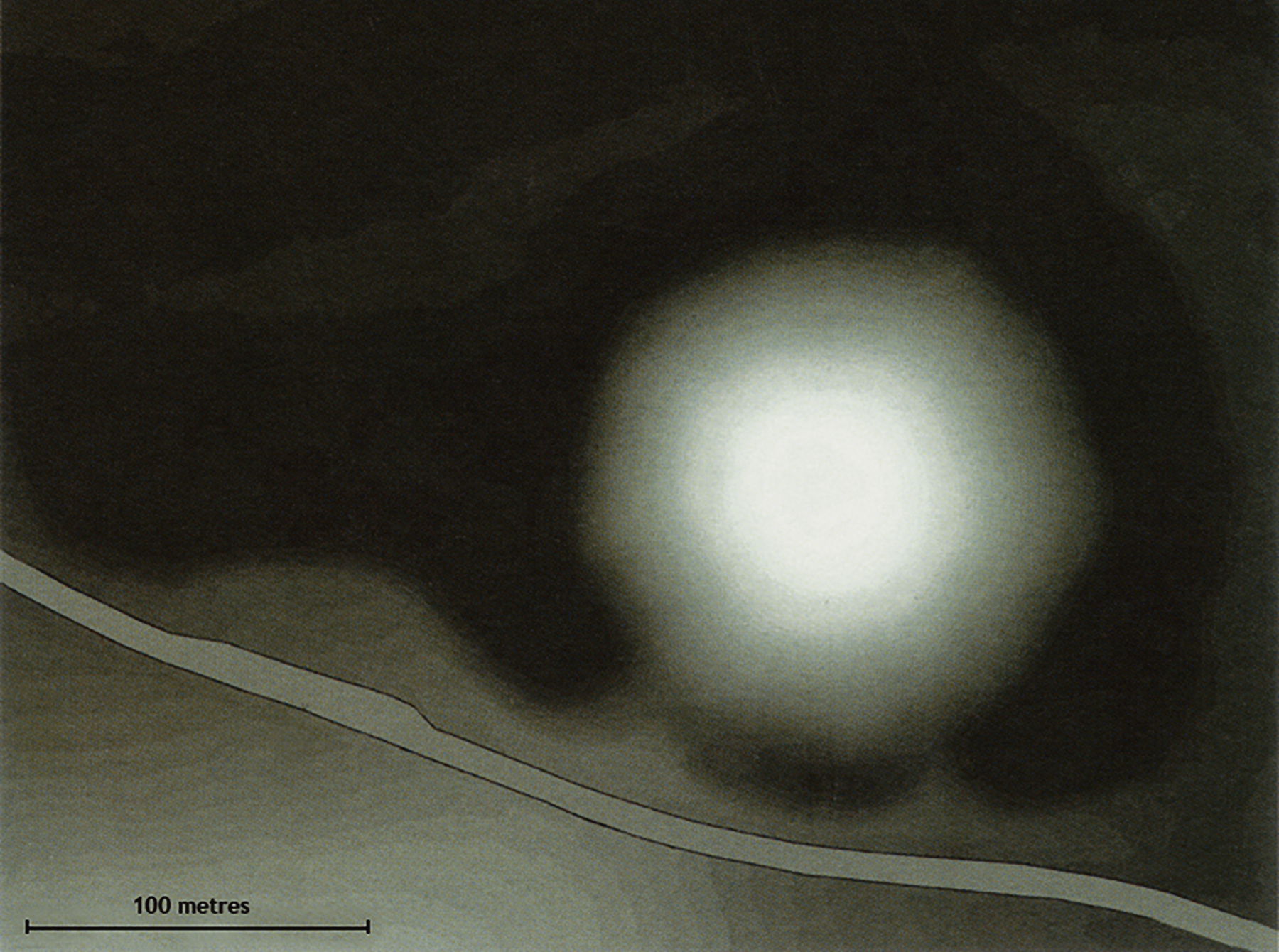

Almost a mile south of the Avebury Henge is Silbury Hill, an immense artificial mound built mostly of chalk rubble, now naturally covered with turf. Surrounding the mound is the Silbury Ditch. Cut deeply into the chalk bedrock, the ditch is quite circular on its eastern and northern sides, but to the west it extends to become almost rectangular. On the south side two causeways run from the roadside footpath to the mound, with only a short section of ditch between them. Silbury is built on the end of a spur reaching northeast from Thorn Hill; part of the spur can still be seen, just beyond the ditch.

When the water table is high, usually in the winter, the ditch fills with water. Silbury Hill is intimately connected with water. To the east of Silbury the river Kennet flows south along the base of Waden Hill but it currently plays no part in filling Silbury's ditch; the ditch's water is supplied by the Beckhampton Stream flowing from several areas of springs to the west, and springs that flow from the edges of the ditch itself.

Silbury's construction required enormous communal effort, yet we can only guess at its original purpose. It was long-assumed to be military, or later, the burial mound of some great king; but despite many excavations, no trace of a burial has been found inside. In fact, nothing at all has been found that gives any indication of Silbury's purpose, though it is generally thought to have had some religious meaning or function.Perhaps Silbury represents the axis mundi - the centre, or navel, of the world. It may be the embodiment of a creation myth, perhaps like the 'earth-diver myth' of native North Americans, in which all the world is water until some animal dives to the bottom of the sea and returns with a mouthful of mud to create the first land. Most of the world's creation myths begin with the forming of waters from chaos; this is often followed by a sexual union of the gods of earth and sky, from which all life descends. The building of a huge mound, watered by springs and rivers, could be seen as a material expression of this concept - a creation myth monumentalised in chalk; a meeting of earth and sky, surrounded by the swirling and bubbling primordial waters of creation.

Silbury has suffered from much excavation over the centuries, since it was long assumed to contain some great secret. Several tunnels were dug into the mound's centre, notably in 1776, 1849 and 1968. Inadequately back-filled, the resulting voids caused a partial collapse of the mound after heavy rains in 2000. Silbury was finally stabilised in 2007-8, with all of its tunnels filled with chalk. Working alongside the engineers who carried out the repair work was a team of archaeologists; the enormous quantity of data they gathered has led to a new understanding of how Silbury was constructed. It was previously assumed that the mound had been 'designed' to be a certain shape and size, then constructed to a fixed plan. The latest evidence, however, suggests that there was no plan: the mound evolved.

The original ground surface on which Silbury was built is chalk bedrock, overlain with clay-with-flints; the soil would be expected to be 20 to 30 cm (up to a foot) thick. Instead, the chalk beneath the mound was covered with just a few millimetres of smooth, grey, silty clay, and was virtually free of stones. This indicates preparation of the site: it seems the topsoil had been stripped away and the subsoil compressed by human and possibly animal feet. If the site was already special, the ground may have taken many years to compress. Had the missing stones been picked out of the clay by hand? In the centre was a hearth - a small scorched area with some charcoal, two burnt pig teeth and a few burnt hazelnut shells.

On top of this thin layer of clay was a pile of gravel almost a metre high and ten metres in diameter. Why was gravel used? It may be that gravel had some ritual significance; it may also be because springwater was flowing up out of the ground. When the Silbury Springs flowed in 2013 they turned some flat areas of ground to a jelly-like consistency as underground springwater flowed directly up to the surface. It is likely that the Silbury site was similarly populated with springs. If so, then covering the saturated ground with gravel would be a practical first step if the area was to be used for any kind of activity.

At some unknown later time the site was enlarged, with a ring of stakes placed around the gravel mound to mark a new perimeter. A waist-high mound of soil, mud and turf was formed. Nearby were two smaller mud mounds, each less than half a metre high - one was like a model of Silbury with a ditch around it. The two mounds that were found just happened to be in an open tunnel: there may well have been others.

The mound was made bigger by piling on more soil; most of it was of a different type, brought in from outside the immediate area. With this were basket-loads of clay, chalk and gravel, and yet more turf. The turves were now from many different locations: it has been suggested that people were travelling from afar to visit Silbury, adding a piece, literally, of their home turf. This complex layer cake of material was seeded throughout with round sarsen boulders. Inside the tunnel, archaeologists saw the many layers in cross section, as interweaving stripes of varying thickness and colour. At this stage the mound was an estimated 35 m across and 5 or 6 m high.

A mighty ditch was dug into the chalk encircling the mound: about 100 m in diameter, it was an impressive 6 m wide and 6.5 m deep. Around two thirds of its present size, the ditch was likely a later feature but it may have been there since work began. Within the ditch, concentric banks, each a few metres apart, surrounded the central organic mound, suggesting that one original bank grew outwards over time. All these features are now buried beneath the mound.

From this point on, it appears that all the material added to the mound was chalk dug from around the mound, creating the ditch. This raises several questions. What was the reason for cutting the ditch? Was the intention to surround the mound with water, or was this an accidental result of excavating material for the mound? Most experts agree that the water table was higher at the time of Silbury's construction, but was this all year round or just in the winter, as it is now? It is hard to imagine that any excavation was possible if the chalk bedrock was underwater, as wet chalk is extremely slippery and the workers would have used antler picks, which are also slippery. The rivers may still have been flowing when the work was done, as they could be dammed or diverted; however it would be well-nigh impossible to stop the springs flowing northeast from Thorn Hill. So it seems highly likely that the Silbury Springs were seasonal, just as they are today, and that they usually dried up in the summer.

After Silbury's initial building stages using several using different materials, all were eventually incorporated into one mound about 5 or 6 m high and 35 m across. From there on, by the addition of successive layers of chalk only, Silbury grew to its present size as a white, chalk mound. Could it be that Silbury continued to grow because of a desire to maintain the whiteness and preserve its presence?

Britain has other more recent chalk monuments, in the form of 'hill figures' such as the famous White Horses of Wiltshire. Every few years the figures must be 'scoured' to preserve their whiteness: this involves more than just removing invasive weeds. All hill figures are on steep hillsides to allow them to be seen from a distance, so winter rain tends to wash any loose chalk downhill. White Horses can turn an unpleasant puce colour in times of high rainfall, as chalk loses its whiteness when saturated. The solution is to apply a top dressing of fresh, white chalk.

Brian Edwards suggests that this may account for Silbury's many successive layers of chalk: a need to whiten and renew the mound resulted in its great size. There are instances around the world of holy places being regularly purified with whitewash; The Bible refers to "whited sepulchres, which indeed appear beautiful outward, but are within full of dead men's bones, and of all uncleanness." (Matthew 23:27).

After its uncertain beginnings, with several small mounds and ditches, Silbury eventually became one single mound, about the size of the Marlborough Mound. From that point on, layer after layer of material was added, mostly chalk. Around 250 of these layers have been recorded, suggesting a regular, possibly annual, ritual or festival that involved covering the mound with fresh chalk dug from the surrounding ditch. Not all the layers are of pure chalk, so was it the whiteness of the material that mattered, or the fact that it was excavated from the ditch? If springs and water were what drew attention to the area originally, it is possible that any material dug from around the mound may have been revered, white or not.

Significantly, Silbury's final, outer layers are quite different, suggesting that the builders attempted to make a final casement - a white coating that was more permanent. Maybe they eventually tired of regularly dressing the mound? Perhaps after so many layers Silbury simply became too large, and adding any more chalk was no longer practical or necessary? For whatever reasons, Silbury's outermost coating is made of horizontal layers of loose crushed chalk, held in place by shallow revetment walls that encircle the mound. Skilfully built from chalk rubble boulders, the walls are angled in towards the mound, making them extremely stable. The loosely-formed rubble walls have voids allowing rainwater to drain away freely, which may be one reason why Silbury has survived for so long.

Why people felt driven to create huge earthen mounds is still a mystery and we can only guess at what the mounds' true purpose may have been. There is though, a definite connection to moving water, as all known examples were built close to rivers and springs.

Also known as Merlin's Mount the Marlborough Mound is now surrounded by buildings, in the grounds of Marlborough College. Rising above the school buildings that closely surround it, the mound is more than 18 m high with a diameter of 83 m at the base. Its dimensions are approximately half those of Silbury Hill, which it closely resembles. Only five miles apart, both monuments are known to date from the Late Neolithic, around 2500 BC.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ British Isles Prehistory Archive

→ British Isles Introduction

→ Stonehenge

→ Avebury

→ Kilmartin Valley

→ The Rock Art of Northumberland

→ Rock Art on the Gower Peninsula

→ Painting the Past

→ Church Hole - Creswell Crags

→ Signalling and Performance

→ Cups and Cairns

→ Ynys Môn, North Wales

→ Bryn Celli Ddu

→ The Prehistory of the Mendip Hills

→ The Red Lady of Paviland

→ Megaliths of the British Isles

→ Stone Age Mammoth Abattoir

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network