The Huashan rock art site of China is located in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, neighbouring with Vietnam. It is generally believed that the rock art at the Huashan site was created between the Warring States Period (403–221 BCE) and Eastern Han dynasty (26–220 CE), by an ethnic group named Luo Yue. This article goes beyond the conventional Chinese perspective, and tries to explore the possible connection between the landscape of the Huashan rock art site and the cosmological beliefs of the Luo Yue people.

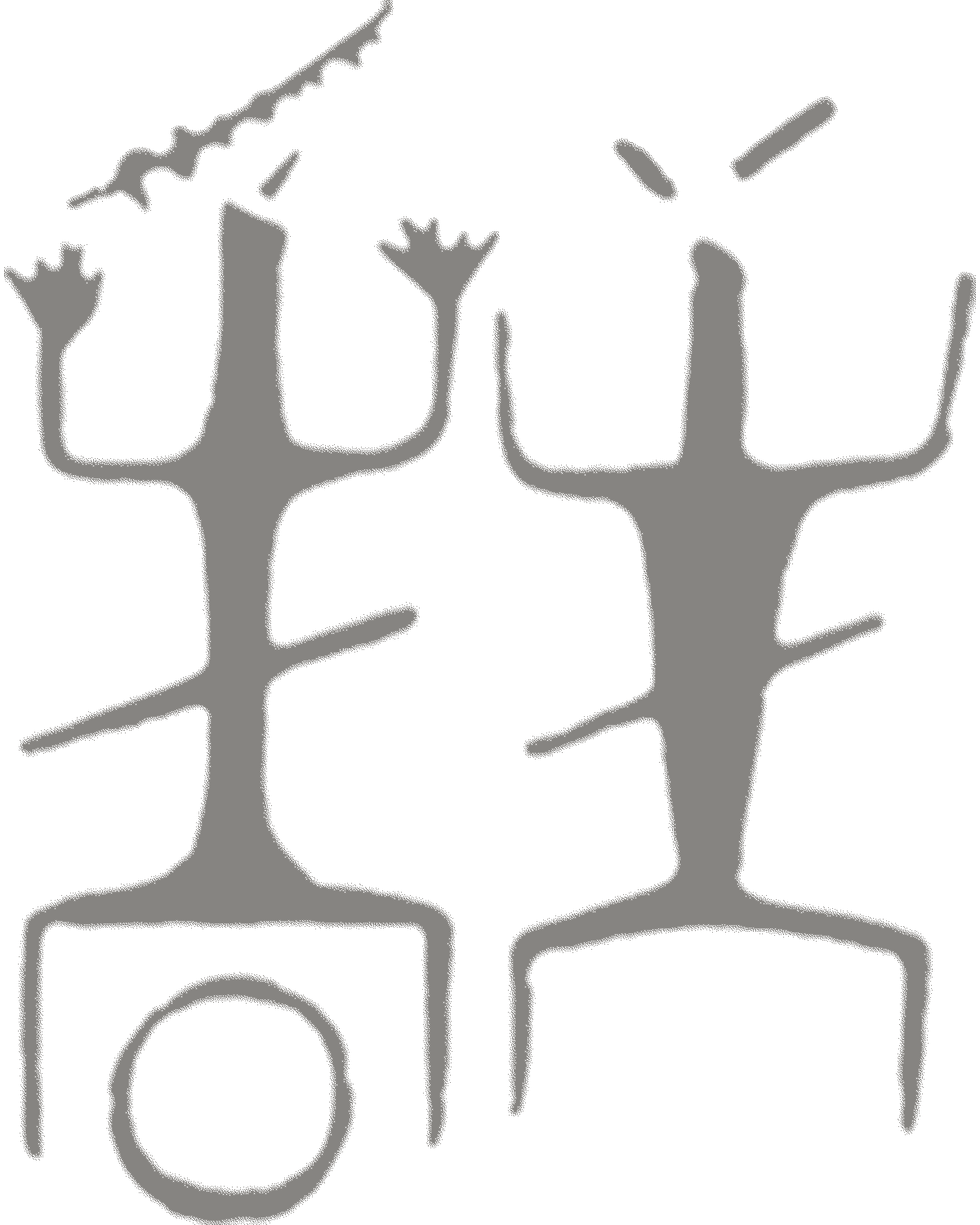

In contrast to other rock art of south-western China, and other rock art traditions from greater China and elsewhere in the world, ‘scenes’ of daily-life activities, such as those described as ‘hunting’, ‘herding’, ‘gathering’ and ‘battling’, are not found in the Huashan panel. Only a few motif types are depicted; these are mainly anthropomorphs, zoomorphs and figures supposedly depicting implements, such as ‘swords’, ‘daggers’, ‘drums’ and ‘bells’. More than 85% of the motifs are anthropomorphous (Qin et al. 1987: 158). These figures are represented either in frontal view or in profile, all with the same posture: arms stretched up at the elbow and legs semi-squatting. With a strong sense of uniformity, the typical composition of the images is one of a large frontal view of a distinctly ‘human’ figure that dominates the centre, mostly with a ‘sword’ hanging at the waist or held in hand, a ‘dog’ under the feet, and a bronze drum-like object nearby, surrounded by lines of smaller profile ‘human’ figures without ‘weapons’.

Over the past few decades, many Chinese scholars (e.g. Qin et al. 1987) have been trying to decipher the meaning of Huashan rock art motifs, with many explanations proposed but no unanimous conclusion drawn so far. As well, anthropologists and ethnographers have documented the accomplishments of the culture and traditions of the local ethnic minorities, whose ancestry is generally considered to have produced the rock art of the Huashan site. This paper will assess the interpretations proposed by Chinese scholars relating the Huashan rock art motifs with the local ethnic culture, and take into consideration the significance of the location of the site itself to provide a novel perspective to understand the production of this extraordinary site.

| Table of Dynasties in Chinese History | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynasty Duration | Major facts | Major facts related to the Huashan area | |

| Xia c.2000-c.1600 BCE | • Mainland China entered the Bronze Age. • The dynasty was founded by the tribe named Huaxia, the ancestral people of the Han Chinese. | • The people loosely belonging to one group, the Yue, who inhabited in the Chinese south-eastern coastal area, founded the Yue state in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River. • It is unclear when was the Yue state first founded. Some argue that the state was established in as early as the Xia period. | |

| Shang c.1600-c1046 BCE | • The Shang Dynasty had a fully developed writing system, preserved on bronze inscriptions and most prolifically on oracle bones. • The large-scale production of bronze-ware vessels and weapons started in early Shang Dynasty. | ||

| Western Zhou 1046-771 BCE | • After its establishment, the Zhou dynasty divided the former Shang lands into hereditary fiefdoms, which later became increasingly independent. • After the Zhou capital Haojing was sacked by the Marquess of Shen and the Quanrong, the Zhou moved its capital eastward to Chengzhou in 771 BCE, which marked the end of the Western Zhou period. | ||

| Eastern Zhou | Spring & Autumn 771-403 BCE | • The Zhou territory was broken up into a multitude of small states that were essentially independent. • As the period unfolded, larger and more powerful states annexed or claimed suzerainty over smaller ones. • A few non-Han states, such as Chu, Shu, and Yue, grew in power in southern China. | • The Yue state had not been mentioned in historical texts until it began a series of wars against its neighbor Wu state in the late 6th century BC. • The Yue state grew in power and expanded its territory after the Yue King Goujian destroyed and annexed the Wu state in 473 BCE. |

| Warring States 403-221 BCE | • It was an era of intensive warfare, and eventually seven major states emerged as the dominant powers. • The Warring States period witnessed the introduction of many innovations to the art of warfare in China, such as the use of iron and of cavalry. • This period is also famous for the development of many philosophical doctrines, the establishment of complex bureaucracies, and a clearly established legal system. | • The Yue state was defeated and annexed by the Chu state in 334 BCE. • After the Yue state was destroyed, the Yue people expanded south-westwards along the coast. • By the late Warring States Period, the Yue people’s expansion covered the whole Chinese southern coastal area and reached northern Vietnam. • Along with the expansion, a number of small kingdoms and principalities emerged. The ancient Han Chinese historians referred to them as ‘Bai Yue’ (literally ‘hundreds of Yue’). • The Luo Yue people was one group of the “Bai Yue”. They were probably a mixture of both the indigenous people and the immigrant Yue people. • It is widely believed that the Luo Yue people, whose territory included the Huashan area, painted the Huashan rock art. | |

| Qin 221-206 BCE | • The Qin state conquered all the other states and established the Qin Empire. • China entered the Imperial Era. • The creation of the Great Wall and the Terracotta Army. • Emperor Qin Shi Huang conquered the southern China. | • Facing with the Qin troops’ invasion, the Luo Yue people, along with other local groups, put up a fierce resistance. • Qin finally conquered south-western China and northern Vietnam in 215 BCE. • Qin divided the new southern conquest into three commanderies: Nanhai, Guilin and Xiang. • In 204 BCE, Zhao Tuo, a military commander of Qin, took control of the three commanderies, and founded the kingdom of Nanyue (‘Southern Yue’). | |

| Western Han 206 BCE - 9CE | • The establishment of the vast trade network known as the Silk Road. • Confucianism became the official state ideology of the Han Empire. • Iron-smelting techniques were greatly improved. | • The Nanyue Kingdom was annexed by the Han Empire in 111 BCE. • The Han Empire incorporated the Nanyue territory into its administrative structure, terming it a Zhou (district), and further sub-divided it into nine Jun (county). | |

| Xin 9-23 CE | • Wang Mang, a powerful relative of the grand empress dowager of Han Empire, seized the throne and established his own dynasty, but was overthrown by rebellions not long after. | ||

| Eastern Han 25-220 CE | • The Silk Road was further developed. • Buddhism was introduced into mainland China from India. | • The Trung sisters, two aristocratic women from the region of Me Linh in current northern Vietnam, rebelled against Han in 40 CE. • The Han general Ma Yuan suppressed the rebellion in 43 CE. • It is believed that the production of rock art in Huashan area most likely ceased in the time of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 CE), when the Han Chinese culture prevailed in this region. | |

| Table of Dynasties in Chinese History 22222 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynasty Duration | |||

| Xia c.2000-c.1600 BCE | |||

| Major facts | |||

| • Mainland China entered the Bronze Age. • The dynasty was founded by the tribe named Huaxia, the ancestral people of the Han Chinese. | |||

| Major facts related to the Huashan area | |||

| • The people loosely belonging to one group, the Yue, who inhabited in the Chinese south-eastern coastal area, founded the Yue state in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River. • It is unclear when was the Yue state first founded. Some argue that the state was established in as early as the Xia period. | |||

| Dynasty Duration | |||

| Shang c.1600-c1046 BCE | |||

| Major facts | |||

| • The Shang Dynasty had a fully developed writing system, preserved on bronze inscriptions and most prolifically on oracle bones. • The large-scale production of bronze-ware vessels and weapons started in early Shang Dynasty. | |||

| Dynasty Duration | |||

| Western Zhou 1046-771 BCE | |||

| Major facts | |||

| • After its establishment, the Zhou dynasty divided the former Shang lands into hereditary fiefdoms, which later became increasingly independent. • After the Zhou capital Haojing was sacked by the Marquess of Shen and the Quanrong, the Zhou moved its capital eastward to Chengzhou in 771 BCE, which marked the end of the Western Zhou period. | |||

| Dynasty Duration | |||

| Eastern Zhou Spring & Autumn 771-403 BCE | |||

| Major facts | |||

| • The Zhou territory was broken up into a multitude of small states that were essentially independent. • As the period unfolded, larger and more powerful states annexed or claimed suzerainty over smaller ones. • A few non-Han states, such as Chu, Shu, and Yue, grew in power in southern China. | |||

| Major facts related to the Huashan area | |||

| • The Yue state had not been mentioned in historical texts until it began a series of wars against its neighbor Wu state in the late 6th century BC. • The Yue state grew in power and expanded its territory after the Yue King Goujian destroyed and annexed the Wu state in 473 BCE. | |||

| Dynasty Duration | |||

| Eastern Zhou Warring States 403-221 BCE | |||

| Major facts | |||

| • It was an era of intensive warfare, and eventually seven major states emerged as the dominant powers. • The Warring States period witnessed the introduction of many innovations to the art of warfare in China, such as the use of iron and of cavalry. • This period is also famous for the development of many philosophical doctrines, the establishment of complex bureaucracies, and a clearly established legal system. | |||

| Major facts related to the Huashan area | |||

| • The Yue state was defeated and annexed by the Chu state in 334 BCE. • After the Yue state was destroyed, the Yue people expanded south-westwards along the coast. • By the late Warring States Period, the Yue people’s expansion covered the whole Chinese southern coastal area and reached northern Vietnam. • Along with the expansion, a number of small kingdoms and principalities emerged. The ancient Han Chinese historians referred to them as ‘Bai Yue’ (literally ‘hundreds of Yue’). • The Luo Yue people was one group of the “Bai Yue”. They were probably a mixture of both the indigenous people and the immigrant Yue people. • It is widely believed that the Luo Yue people, whose territory included the Huashan area, painted the Huashan rock art. | |||

| Dynasty Duration | |||

| Qin 221-206 BCE | |||

| Major facts | |||

| • The Qin state conquered all the other states and established the Qin Empire. • China entered the Imperial Era. • The creation of the Great Wall and the Terracotta Army. • Emperor Qin Shi Huang conquered the southern China. | |||

| Major facts related to the Huashan area | |||

| • Facing with the Qin troops’ invasion, the Luo Yue people, along with other local groups, put up a fierce resistance. • Qin finally conquered south-western China and northern Vietnam in 215 BCE. • Qin divided the new southern conquest into three commanderies: Nanhai, Guilin and Xiang. • In 204 BCE, Zhao Tuo, a military commander of Qin, took control of the three commanderies, and founded the kingdom of Nanyue (‘Southern Yue’). | |||

| Dynasty Duration | |||

| Western Han 206 BCE - 9CE | |||

| Major facts | |||

| • The establishment of the vast trade network known as the Silk Road. • Confucianism became the official state ideology of the Han Empire. • Iron-smelting techniques were greatly improved. | |||

| Major facts related to the Huashan area | |||

| • The Nanyue Kingdom was annexed by the Han Empire in 111 BCE.. • The Han Empire incorporated the Nanyue territory into its administrative structure, terming it a Zhou (district), and further sub-divided it into nine Jun (county). | |||

| Dynasty Duration | |||

| Xin 9-23 CEE | |||

| Major facts | |||

| • Wang Mang, a powerful relative of the grand empress dowager of Han Empire, seized the throne and established his own dynasty, but was overthrown by rebellions not long after. | |||

| Dynasty Duration | |||

| Eastern Han 25-220 CE | |||

| Major facts | |||

| • The Silk Road was further developed. • Buddhism was introduced into mainland China from India. | |||

| Major facts related to the Huashan area | |||

| • The Trung sisters, two aristocratic women from the region of Me Linh in current northern Vietnam, rebelled against Han in 40 CE. • The Han general Ma Yuan suppressed the rebellion in 43 CE. • It is believed that the production of rock art in Huashan area most likely ceased in the time of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 CE), when the Han Chinese culture prevailed in this region. | |||

I undertook this Huashan rock art site research during my MA in archaeology study in Durham University (United Kingdom) and the article has been completed during my doctoral research at the University of Barcelona. I have been very fortunate in my choice of supervisor in Durham University and so would like to especially thank Professor Margarita Díaz-Andreu (now University of Barcelona), for her continued guidance, great patience, invaluable support and constant inspiration. I would also like to express my gratitude to Professor Magnus Fiskesjö (Cornell University) and Professor Paul Taçon (Griffith University), for their kind help, great support and precious advices. The four anonymous referees of Rock Art Research are also thanked for comments that improved this paper.

Qian Gao

Departament de Prehistòria, H. Antiga i Arqueologia

Facultat de Geografia i Història

Universitat de Barcelona

Carrer de Montalegre, 6.

08001 Barcelona

Spain

sarahqiangao@gmail.com

Qian Gao is a member of the Rock Art Network

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ The Huashan Rock Art Site

→ Sacred Meeting Place for Sky, Water and Earth

→ Introduction to the Huashan Rock Art Site

→ UNESCO World Heritage Site

→ Huashan Rock Art Gallery

→ Huashan Local Ethnic Culture

→ Huashan Historical Background

→ Religious Beliefs of the Luo Yue

→ Cosmology of Huashan Rock Art

→ 38 Huashan Rock Art Sites

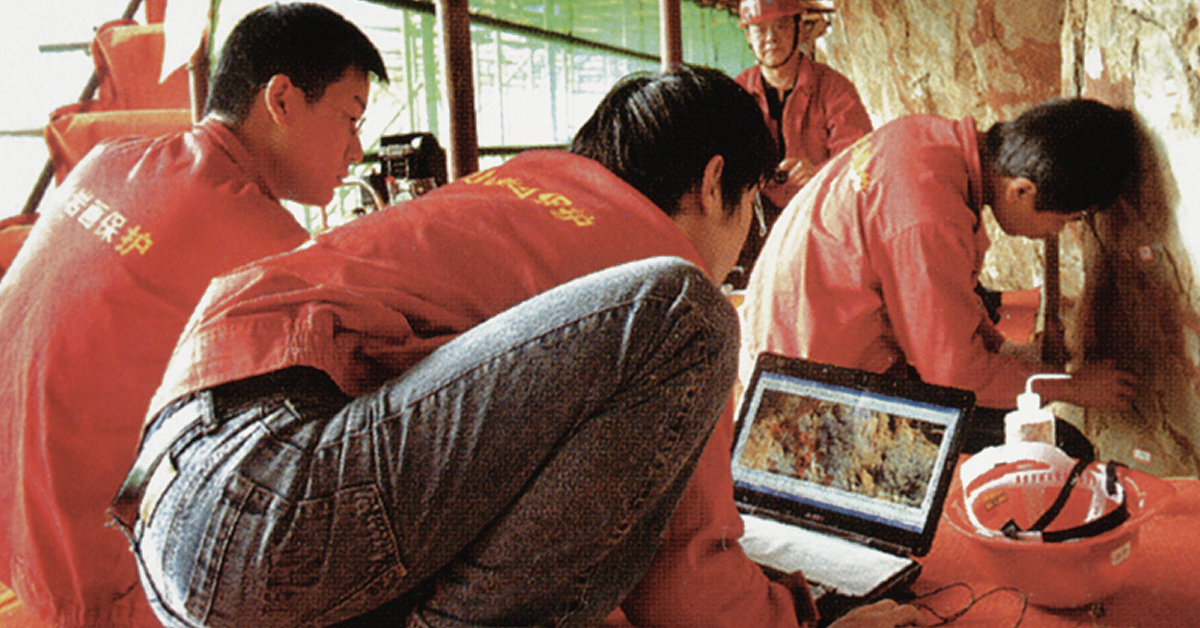

→ Protection of Zuojiang Huashan

→ Wushan Rock Art

→ China Rock Art Archive

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network