The article 'Walking with cavemen', written by Christopher Ken in NewScientist, describes a novel approach to interpreting and understanding prehistoric evidence

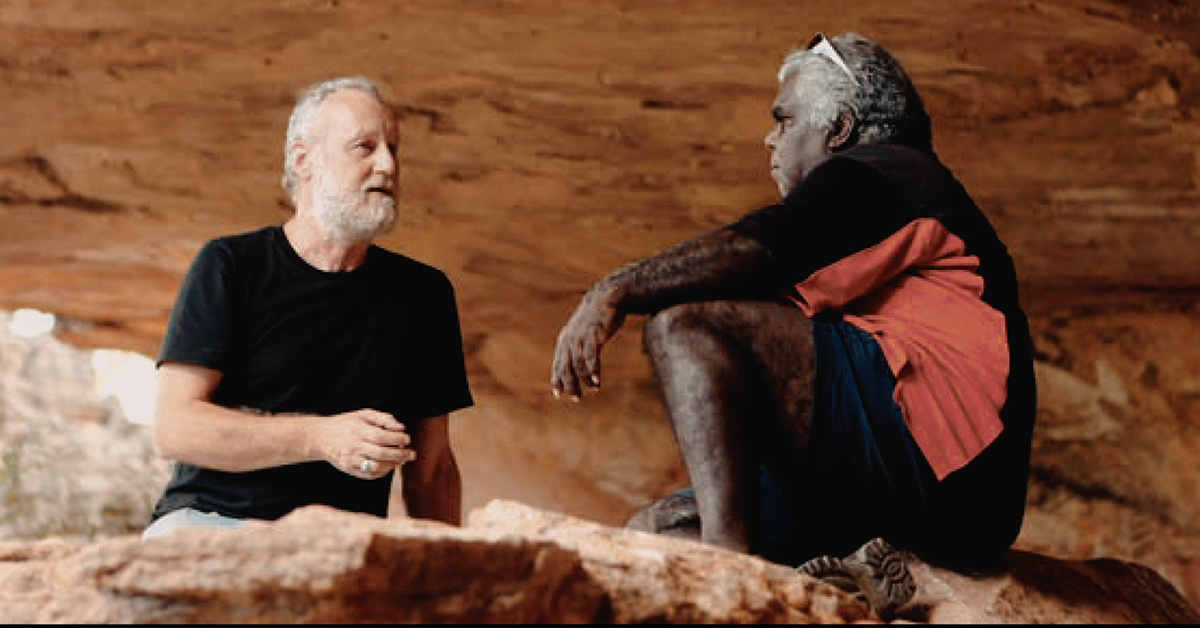

'In the darkened recesses of a remote cave in the Pyrenees, three Namibians crouch over something in the ground. They have travelled to France from the Kalahari desert, more than 7,000 kilometres away. The cave is cold and wet, and they are wearing waterproofs, hard hats and headlamps. Each holds a laser pointer. As they huddle together, talking in Ju/'hoan- their native dialect - red points of light bounce around the cave floor, finally settling on a semicircular depression. It is a print made by a human heel.

The footprint dates from the Magdalenian period of the European Upper Palaeolithic - about 17,000 years ago. The Namibians are San bushmen who were brought here by archaeologist Tilman Lenssen-Erz of the University of Cologne in Germany. He and Andreas Pastoors from the Neanderthal Museum in Mettmann, Germany, believe these three men can read the contours of the footprint with greater insight and accuracy than anyone else in the world.

Scattered across the south-west of Europe are approximately 350 caves decorated with vivid Palaeolithic art. A handful of lesser-known ones also contain something just as spectacular: ice-age human footprints, preserved by a thin crust of calcite.

Three of these caves - Les Trois Freres, Tuc d'Audoubert and Enlene, collectively known as the Cavernes du Volp - are hidden in the Pyrenean foothills. Owned for generations by the aristocratic Begouen family and closed to the public, they form a series of limestone chambers twisting and corkscrewing underground, carved by a subterranean stream.

The caves are like windows on life during the last ice age. But only to those who can read what was left behind.

Seventeen thousand years ago, southern France was a cold, treeless landscape sparsely populated by semi-nomadic people. They hunted bison, reindeer and wild horses using spears and traps. They made tools and clothing. And they filled the caves with art, including paintings, figurines and clay sculptures.

The Namibians are not here for the art. The San are renowned trackers, and they are here to read the footprints.

"All three learned tracking from their fathers," he says. "They have been working all their lives, mainly for trophy hunters. Their tracking skills are highly developed and used on a daily basis."

The project began in 2010. Lenssen-Erz says he was interested in using trackers from the beginning. Through Megan Biesele, a US anthropologist who has worked in the Kalahari since the 1970's, he hired Tsamkxao Cigae, a young tracker who also became their interpreter. Cigae brought on board two more experienced trackers, C/wi /Kunta and C/wi G/aqo De!u.

Lenssen-Erz visited the trackers in Namibia several times to prepare them for what lay ahead. They went tracking together. "We went to some dried-out salt pans where there are a lot of tracks," he says. "We made a square of something like 4 by 4 metres, and we asked them, 'Could you tell us the story of this place?'". The San were able to narrate the movements of animals that had passed over the area in the previous 72 hours.

He also took them to a cave in Botswana - an environment they had never encountered before. On another occasion, they visited Cologne zoo in Germany to look at bear tracks, which they had never seen before but expected to find in the caves.

In July, the team was ready. They headed to France and entered Tuc d'Audoubert. For two weeks, they crawled through the cave, allowing the bushmen as much time as they needed to inspect the prehistoric spoor.

"We had laser pointers and we handed them to the trackers while they were discussing the spoor," Lenssen-Erz says. "They were using them extensively, so we would always know what they were talking about. They passed minutes and minutes discussing smali depressions or small elevations in the ground."

After discussing a footprint, the bushmen were able to confidently state the sex and age of the person who had made it 17,000 years ago. "They never get lost in speculation," says Lenssen-Erz. "They would be standing there discussing among themselves and then Cigae would say, very clearly: 'Female spoor, 28-years-old,' or 'This is a young man of 18 years.'"

Using information gathered by the trackers, Lenssen-Erz built a detailed census of the individuals who had used the cave for shelter during the last ice age.

"We have a spectrum of ages, from the very young to the very old," he says. "The youngest is a 3-year-old boy, and the oldest is a 60-year-old man. In between, there are people of all ages. The demography that we have now is about something like 28 people, which is very nice because we have very little data in archaeology on demography."

The project is ongoing and translators are currently transcribing recording of everything the trackers said during their time in the caves.

Some of the information the trackers gave conflicted with previous studies. For instance, one set of tracks had previously been interpreted as being made by several people performing a ritual dance. The San trackers, however, say those marks were left by a single person - a 14-year-old girl - playfully pushing her feet into the soft ground.

Researchers have used indigenous people to assess prehistoric footprints before. In 2003, while doing fieldwork in a remote part of New South Wales in Australia, anthropologist Steve Webb of Bond University in Queensland discovered a site covered with human footprints left about 20,000 years ago. "We revealed more and more prints -prints of children, women, men hunting." Webb contacted the Pintubi, an indigenous people, to tell him more. "These people live by marks on the ground," he says. "They started to say, 'These are children of this age, and that'sa woman over there. She's got a baby in her arms.' I was stunned."

Despite his own successes, Webb warns that the technique has limitations. In particular, he doubts that ice-age people survived to 60. "I don't doubt there were old people," he says, "but it might be that, in fact, they're not actually that age. They could just have bodies that are worn out, because it's a hard life."

Lenssen-Erz and Pastoors plan to return to the caves with the trackers in 2015 to get a better understanding of how the San gather so much information from a print. "When we tried to find out how they do it they just said, 'they look different'," says Lenssen-Erz. "It's like asking a sommelier to explain how they differentiate one wine from the other. They would just say, they are different. They just taste it. And the San just see it."

Extract taken from NewScientist, December 2013

'Walking with cavemen' by Christopher Ken

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 06 December 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 29 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 25 October 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 12 July 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 24 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 20 April 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 01 April 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 23 February 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 14 January 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 18 December 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Sunday 06 December 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 07 October 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 06 December 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 29 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 25 October 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 12 July 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 24 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 20 April 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 01 April 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 23 February 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 14 January 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 18 December 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Sunday 06 December 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 07 October 2020

Friend of the Foundation