An article provided by the University of Utah on phys.org - New hypothesis explains how human ancestors used fire to their advantage - reports on fire, a tool broadly used for cooking, constructing, hunting and even communicating, and arguably one of the earliest discoveries in human history. But when, how and why did fire come to be used?

how #human #ancestors used fire to their advantagehttps://t.co/i7vGaFzJQE pic.twitter.com/WdqMfYlzLx

— Bradshaw Foundation (@BradshawFND) April 18, 2016

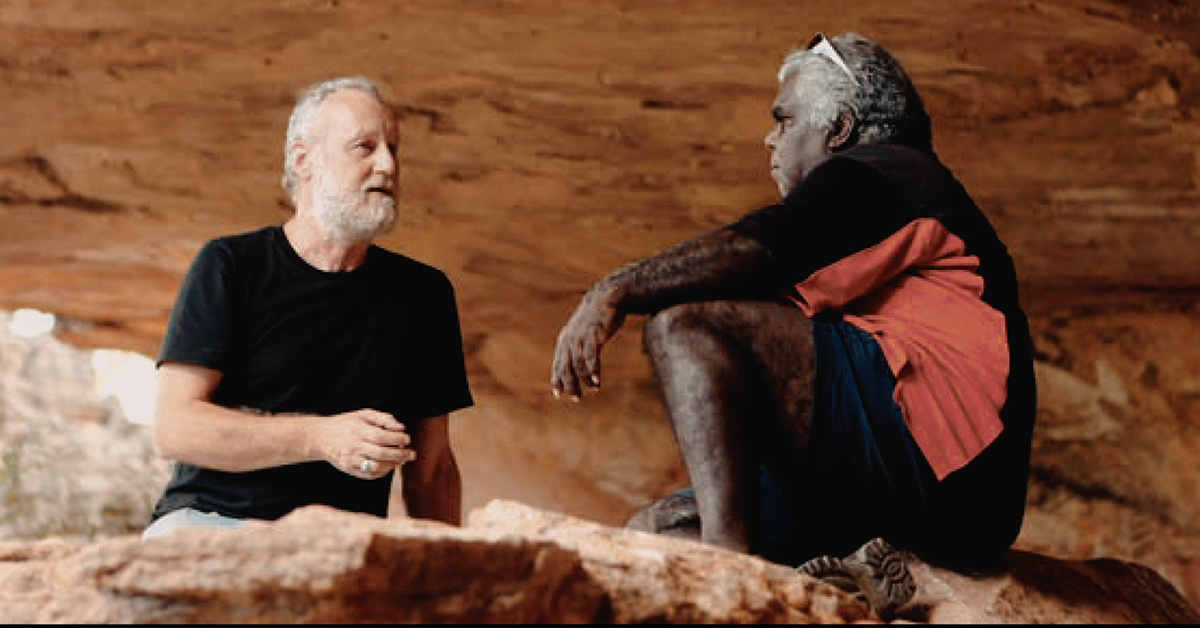

The Hadza people, an indigenous ethnic group in Tanzania, are among the last hunter-gatherers in the world who forage in burns. Image: James F. O'Connell

A new scenario crafted by University of Utah anthropologists proposes that human ancestors became dependent on fire as a result of Africa's increasingly fire-prone environment 2-3 million years ago.

As the environment became drier and natural fires occurred more frequently, ancestral humans took advantage of these fires to more efficiently search for and handle food. With increased resources and energy, these ancestors were able to travel farther distances and expand to other continents.

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation and the findings were published April 10, 2016 in Evolutionary Anthropology: Christopher H. Parker et al. The pyrophilic primate hypothesis,'Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews' (2016). DOI: 10.1002/evan.21475

Current prevailing hypotheses of how human ancestors became fire-dependent depict fire as an accident - a byproduct of another event rather than a standalone occurrence. For example, fire as a result of rock pounding that created a spark and spread to a nearby bush.

However, Kristen Hawkes, professor of anthropology, Christopher Parker, anthropology postdoctoral research associate, Earl Keefe, postdoctoral research associate Nicole Herzog and professor James F O'Connell, suggest that fire use is so crucial to our biology, it seems unlikely that it wasn't taken advantage of by our ancestors.

New Proposal: the team's proposed scenario is the first known hypothesis in which fire does not originate serendipitously. Instead, the team suggests that the genus Homo, which includes modern humans and their close relatives, adapted to progressively fire-prone environments caused by increased aridity and flammable landscapes by exploiting fire's food foraging benefits - essentially taking advantage of landscape fires to forage more efficiently.

By reconstructing tropical Africa's climate and vegetation about 2-3 million years ago, the research team pieced together multiple lines of evidence to craft their proposed scenario for how early human ancestors first used fire to their advantage.

To clarify the dating and scope of increasingly fire-prone landscapes, the research team took advantage of recent work on carbon isotopes in paleosols. Because woody plants and more fire-prone tropical grasses use different photosynthetic pathways that result in distinct variants of carbon, the carbon isotopic composition of paleosols can directly indicate the percentage of woody plants versus tropical grasses.

Recent carbon analyses of paleosols from the Awash Valley in Ethiopia and Omo-Turkana basin in northern Kenya and southern Ethiopia show a consistent pattern of woody plants being replaced by more tropical, fire-prone grasses approximately 3.6-1.4 million years ago. This is explained by reductions in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and increased aridity. Drier conditions and the expansion of fire-prone grasslands are also evidenced in fossil wood evidence in Omo Shungura G Formation, Ethiopia.

As the ecosystem became increasingly arid and a pattern of rapid, recurring fluctuation between woodlands and open grasslands emerged, many ancestral humans adapted to eating grassland plants and food cooked by fires. In essence, they took advantage of the foraging benefits that fire provided.

Fire-altered landscapes provided foraging benefits by improving both the processes of searching for and handling food.

How? The research team identified these benefits by using the prey/optimal diet model of foraging, which simplifies foraging into two mutually exclusive components - searching and handling - and ranks resources by the expected net profit of energy per unit of time spent handling. This model identifies changes in the suite of resources that give the highest overall rate of gain as search and handling costs change.

By burning off cover and exposing previously obscured holes and animal tracks, fire reduces search time; it also clears the land for faster growing, fire-adapted foliage. Foods altered by burning take less effort to chew and nutrients in seeds and tubers can be more readily digested. Those changes reduce handling efforts and increase the value of those foods.

This may explain the mismatch between the fossil and archaeological records. Anatomical changes associated with dependence on cooked food such as reduced tooth size and structures related to chewing appear long before there is clear archaeological evidence of cooking hearths. The earliest forms of fire use by the genus Homo would not have left traces in the form of traditional fire hearths. Instead of cooking over a prepared hearth that would be visible archaeologically, hominins were taking advantage of burns - early fire use would have been indistinguishable from naturally occurring fires. This scenario tells a story about our ancestors' foraging strategies and how those strategies allowed our ancestors to colonize new habitats.

Future research: the team will take on an ethnographic project with the Hadza people, an indigenous ethnic group in Tanzania that are among the last hunter-gatherers in the world, to learn how they forage in burns.

Read more in the ORIGINS section:

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 October 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 25 June 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 09 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 03 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 28 October 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 23 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 04 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 14 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 February 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 28 November 2019

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 October 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 25 June 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 09 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 03 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 28 October 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 23 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 04 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 14 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 February 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 28 November 2019

Friend of the Foundation