This list, created within the Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage adopted by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1972, is an instrument to protect sites considered to be of extraordinary cultural and/or natural value, which are therefore considered the concern of all of humanity.

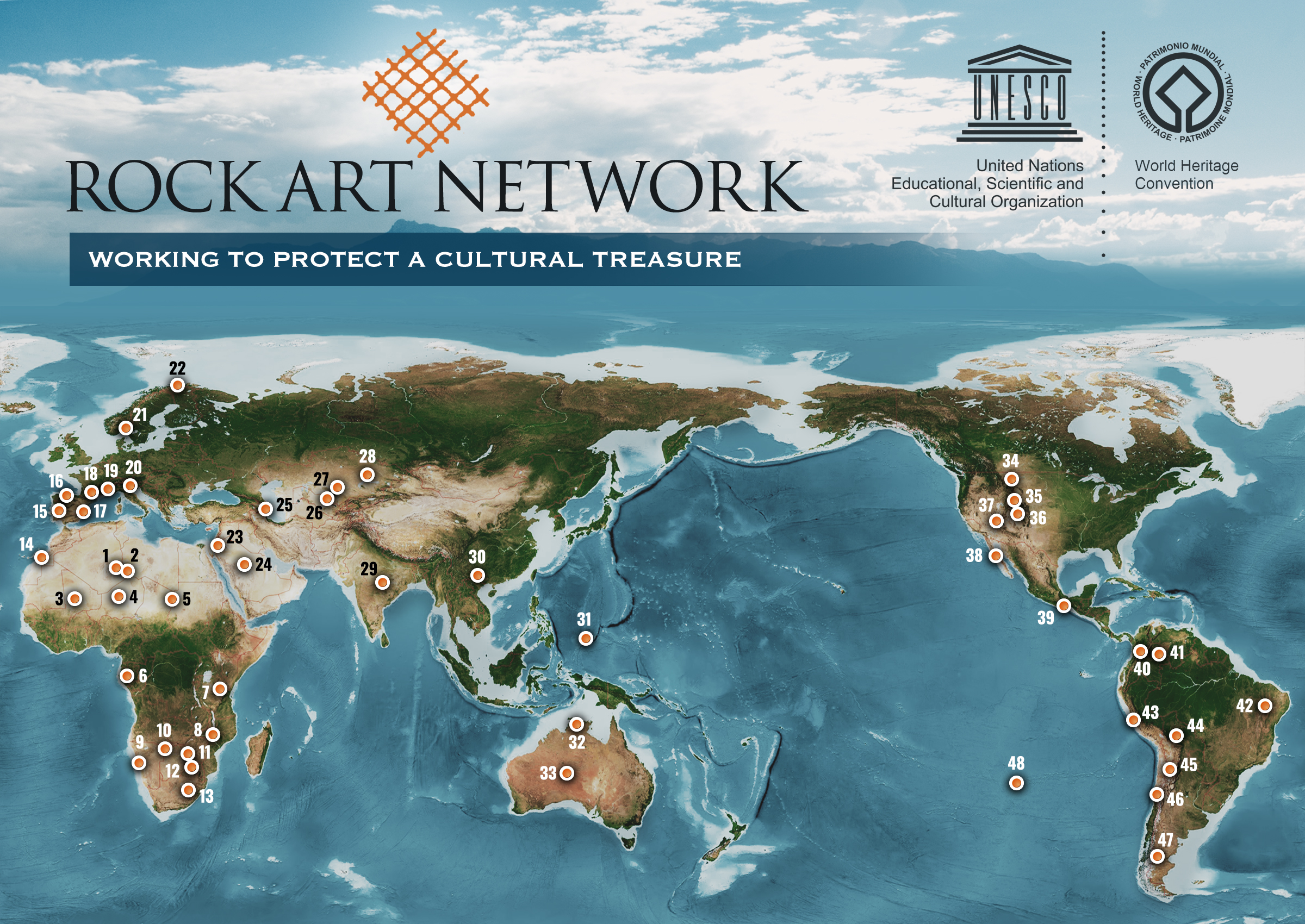

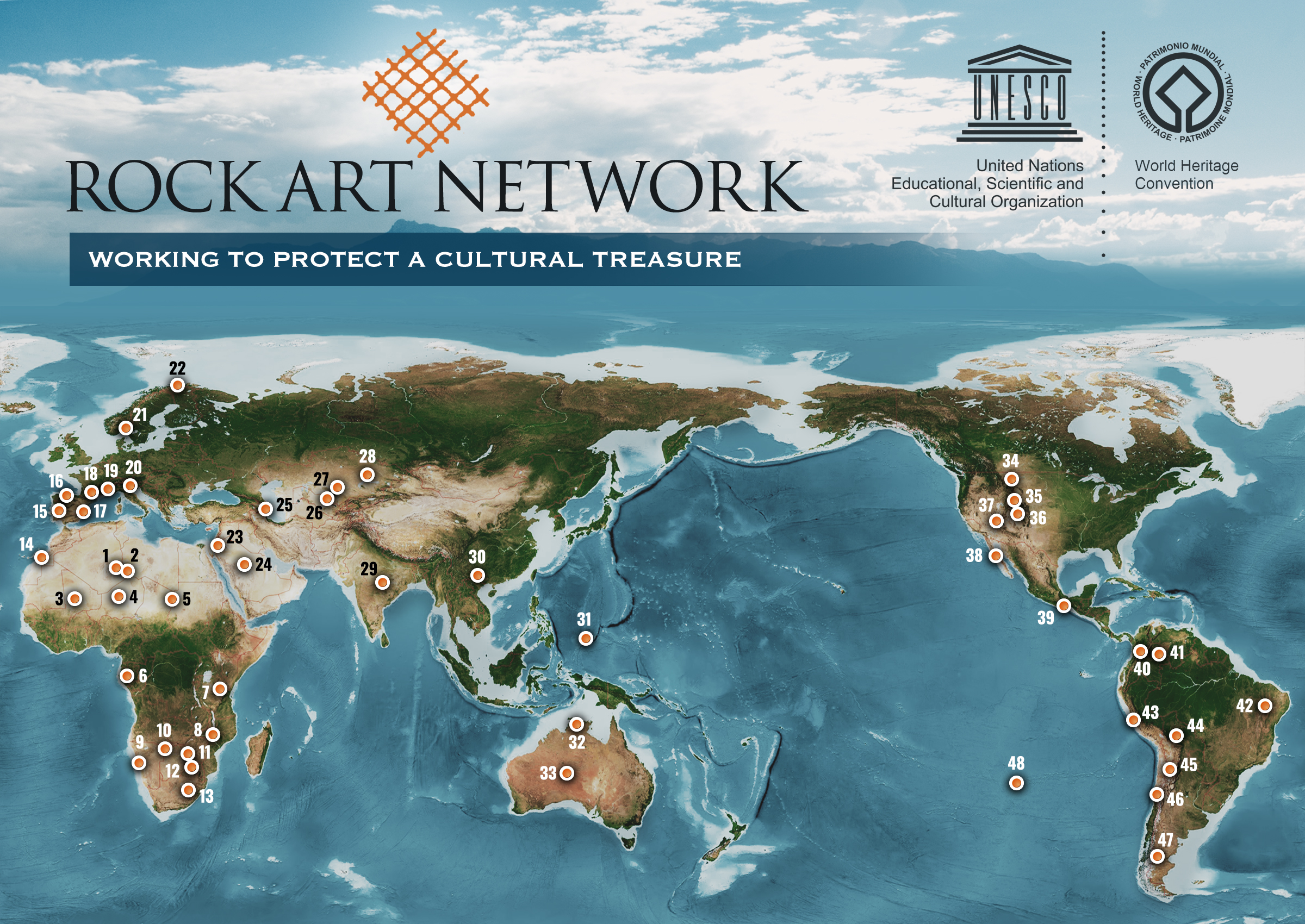

Among all the World Heritage sites, almost 50 contain rock art, specifically 48 of them. In most of them, the rock art itself is the World Heritage, while in others it is one of the added values of a landscape or natural area which is also categorised as a World Heritage Site. This large number reflects the fact that rock art is the only universal art form over time and space; it is the oldest art form made from 43,000 years ago until today. This exceptional, universal feature of rock art has gradually been reflected on the List until reaching the current map, which reveals its widespread geographic distribution (above).

Chronologically, the first two rock art sites to be designated World Heritage Sites were the Prehistoric Sites and Decorated Caves of the Vézère Valley in France and the Rock Drawings in Valcamonica in Italy, both in 1979. In 1985, the Cave of Altamira in Spain (Figure 1), the Rock Art of Alta in Norway and the Rock-Art Sites of Tadrart Acacus in Libya were added. Very few were considered again until 1994: the Serra da Capivara National Park in Brazil, the Rock Paintings of the Sierra de San Francisco in Mexico (Figure 2), the Lines and Geoglyphs of Nasca and Palpa in Peru and the Rock Carvings in Tanum in Sweden. Furthermore, other sites that contain rock art are registered on the World Heritage List of Natural Sites, such as Mesa Verde National Park in the United States, Kakadu National Park in Australia and Tassili n’Ajjer in Algeria.

After realising this, the Committee presented the Global strategy for a representative, balanced and credible World Heritage List, which set new registration strategies to make the list more varied, more representative of the world’s cultural and natural richness and more geographically balanced. Since then, virtually every year, and sometimes twice a year, sites with rock art have been honoured as World Heritage.

Indeed, rock art can be found in all inhabited regions of the world: forests, steppes or deserts, mountains or valleys; in the depths of caverns or in open shelters and rock pools. All we have to do is look at landscapes like the deserts in the Air and Ténéré Natural Reserves in Niger, where huge rocks are peppered with engravings of elephants, oryxes, giraffes, ostriches and gazelles; the steep cliff walls of the Grand Canyon and Chaco Canyon in the United States; and the almost glacial landscapes like Alta in Norway.

While in Palaeolithic art, the oldest form existing, few human figures were painted or carved and the depictions are not very naturalistic, since around 10,000 years ago people have featured in rock art in hunting, gathering, grazing, dancing or fighting scenes. Magnificent examples can be found in the Rock Art of the Iberian Mediterranean Basin and the Cliff of Bandiagara in Mali, as well as the vast red and black figures in Mexico’s Rock Paintings of Sierra de San Francisco. In contrast, depictions of anatomical parts like the vulva and especially the hand, either in outline or as handprints, have been common motifs on five continents since the most ancient art; the best example is unquestionably Cueva de las Manos in Argentina.

When what is depicted has no counterpart in nature, we tend to call it a sign. They are also quite frequent and widespread throughout the world and over time; they can be simple geometric shapes like triangles, circles, rectangles or dots, or more complex shapes like spirals and labyrinths, and they can come in multiple variations and combinations. They are found in almost all European caves with Palaeolithic rock art, in Africa in Chongoni (Malawi) and Lopé-Okanda (Gabon), in the Americas in Yagul and Mitla in Mexico, in Australia in Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park and Kakadu National Park, and more recently the carvings in Sulaiman-Too Sacred Mountain in Kyrgyzstan.

However, if all rock art has one thing in common, it’s unquestionably its fragility, since it is constantly exposed to both natural and human-made factors which can degrade it. In addition to raising awareness of the need to enlist everyone in safeguarding this heritage, UNESCO also created the List of World Heritage in Danger for all sites that run the risk of disappearing or seriously deteriorating. Today, the Rock-Art Sites of Tadrart Acacus in Libya and Air and Ténéré Natural Reserves in Niger are on this list, both of them due to the social instability of the two countries.

One can only conclude that rock art is a visual book recounting our history and our way of understanding the world. Yet it’s not only about the past but is also part of our identity, of what we are today, and it’s even living culture in numerous communities. Therefore, both the oldest and the most recent rock art become meaningful in their contexts, meaning their landscape, society and culture. Understanding this should lead us to appreciate the extraordinary importance of this cultural expression and the need to preserve not only its physical integrity through protection and conservation measures but also its associated values. Those sites on the World Heritage List have already been showcased and protected, but let us not forget that there may be as many as 400,000 known sites with rock art on the planet, and they all share the values and features outlined here. Therefore, we all can and should contribute to preserving them.

Esta Lista, también conocida como Patrimonio de la Humanidad, es un instrumento para la protección de los bienes considerados de gran riqueza cultural y/o natural y que, por tanto, se consideran relevantes para toda la humanidad. Esta Lista fue creada en el marco de la Convención para la Protección del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural adoptada por la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura – UNESCO – en 1972.

Si de entre todos los sitios Patrimonio Mundial seleccionamos los que contienen arte rupestre, podemos llegar al medio centenar, 48 en concreto. En su mayoría, el arte rupestre es el bien en sí mismo Patrimonio Mundial; en otros, es uno de los valores añadidos de un paisaje o área natural con la misma consideración. Este alto número obedece al hecho de que el arte rupestre es el único hecho artístico universal en el tiempo y en el espacio; es el arte más antiguo, realizado desde hace más de 43 000 años hasta la actualidad. Esa excepcionalidad y universalidad se ha ido viendo reflejada en la Lista de forma paulatina hasta conformar el actual mapa en que se puede constatar su enorme distribución geográfica.

Cronológicamente los dos primeros sitios con arte rupestre en ser designados Patrimonio Mundial fueron los sitios prehistóricos y cuevas con pinturas del Valle del Vézère en Francia y el arte rupestre de Val Camónica de Italia, ambos en 1979. En 1985 se inscribe la cueva de Altamira de España (Figura 1), el arte rupestre de Alta en Noruega y los sitios rupestres de Tadrart Acacus en Libia. Hasta 1994 pocos más reciben esta consideración: el Parque Nacional de Sierra de Capivara en Brasil, las pinturas rupestres de la Sierra de San Francisco en México (Figura 2), las líneas y geoglifos de Nazca y Pampas de Jumana de Perú y los grabados rupestres de Tanum en Suecia. Además otros sitios que contienen arte rupestre son inscritos en la Lista de bienes naturales como el Parque Nacional de Mesa Verde en Estados Unidos, el Parque Nacional de Kakadú en Australia o Tassili N’Ajjer en Argelia.

Tras esta constatación, el Comité presenta la “Estrategia global para una Lista del Patrimonio Mundial equilibrada, representativa y creíble” que marca nuevas estrategias de inscripción para que la Lista sea más variada, más representativa de la riqueza cultural y natural del mundo, y geográficamente equilibrada. A partir de entonces, prácticamente todos los años e incluso algunos años por partida doble, se ha otorgado la categoría de Patrimonio Mundial a sitios con arte rupestre.

Porque efectivamente encontramos arte rupestre en todas las regiones del mundo que habitamos: bosques, estepas o desiertos, montañas o valles; en la profundidad de las cavernas o en abrigos y rocas al aire libre. Basta contemplar paisajes como los desiertos en las reservas naturales del Air y del Teneré en Níger donde grandes rocas están cuajadas de grabados de elefantes, orix, jirafas, avestruces y gacelas, las escarpadas paredes del Gran Cañón o del Cañón Chaco en Estados Unidos o los paisajes casi glaciares como Alta en Noruega.

En cuanto a los temas representados, el mayor porcentaje son animales, aquellos característicos del paisaje o el clima en el que fueron realizados: elands en el Parque Maloti – Drakensberg de Sudáfrica y Lesotho, guanacos en la cueva de Las Manos en la Patagonia argentina, jirafas, leones y rinocerontes como en Twyfelfontein (Figura 3) en Namibia o Matobo en Zimbabwe, caballos como en el paisaje arqueológico de Tamgaly en Kazajastán, camellos en Uadi Rum en Jordania o ciervos, bisontes, caballos y cabras como en las cuevas con arte rupestre paleolítico del norte de España que acompañan a Altamira en su condición de Patrimonio Mundial desde 2008.

Cuando lo representado no tiene un referente natural solemos llamarle signo. También es muy frecuente y amplia- mente extendida en todo el mundo y cronología su representación; pueden ser formas geométricas simples como triángulos, círculos, rectángulos o puntos, hasta más otras complejas como espirales o laberintos, y con múltiples variantes y combinaciones: los hay en casi todas las cuevas europeas con arte rupestre paleolítico, en África como en Chongoni (Malawi) o Lopé Okanda (Gabón), en América como en las mexicanas Yagul y Mitla, Australia como en el Parque Ulurú como en Kadadú y de fechas recientes como los grabados de la montaña sagrada de Sulaiman-Too en Kirguizistán.

Pero si hay algo común a todo el arte rupestre es, sin duda, su fragilidad pues está expuesto permanentemente a factores de degradación, no sólo naturales sino también los provocados por los humanos. UNESCO, además de concienciar de la necesaria implicación de todos en la salvaguarda de este patrimonio, también creó la Lista de Patrimonio Mundial en Peligro para aquellos bienes que corrieran riesgo de desaparición o grave deterioro. Hoy, Tadrart Acacus en Libia y Air y Teneré en Níger están en esta Lista, en ambos casos por la inestabilidad social de ambos países.

Solo resta concluir que el arte rupestre es un libro visual de nuestra historia, de nuestra forma de comprender el mundo, pero no es sólo historia pasada pues forma parte de nuestra identidad, de lo que hoy somos, e incluso es cultura viva entre numerosas comunidades. Así, el arte rupestre más antiguo y el más actual tiene sentido en su contexto entendido como paisaje, sociedad y cultura. Entender esto debe llevarnos a valorar la gran relevancia de esta manifestación cultural y la necesidad de preservar no solo su integridad física a través de medidas de protección y conservación, sino sus valores asociados. Aquellos sitios que están en la Lista de Patrimonio Mundial ya han sido destacados y protegidos, pero no olvidemos que los sitios con arte rupestre conocidos en el planeta pueden alcanzar la cifra de 400.000 y todos ellos comparten los valores y características aquí enunciados y por ello todos podemos y debemos contribuir a su preservación.