This region was occupied by Upper Palaeolithic groups for millenia; indeed, the groups formed a cultural society, using this and other nearby caves such as La Clotilde, El Linar, Las Aguas, Cualventi, La Meaza, Cudón, El Castillo, La Pasiega, Las Chimeneas, Las Monedas, Hornos de la Peña, Morin, El Pendo, Santián, El Juyo, Camargo, and El Ruso, among others.

The cave of Altamira, with its twisting passages and chambers, is roughly 270 metres. The main passage is at times six metres in height. Archaeological excavations in the cave have revealed Palaeolithic artifacts from the Gravettian (roughly 22.000 years ago) to the Middle Magdalenian (between roughly 16.500 and 13.000 years ago).

The cave was inhabited by different groups of people between these two periods. The location of the cave was clearly favourable for occupation, with a landscape of valleys and mountains as well as the nearby coastal region. Roughly 13,000 years ago a rock fall sealed off the cave's entrance; Altamira remained sealed until its rediscovery in 1868.

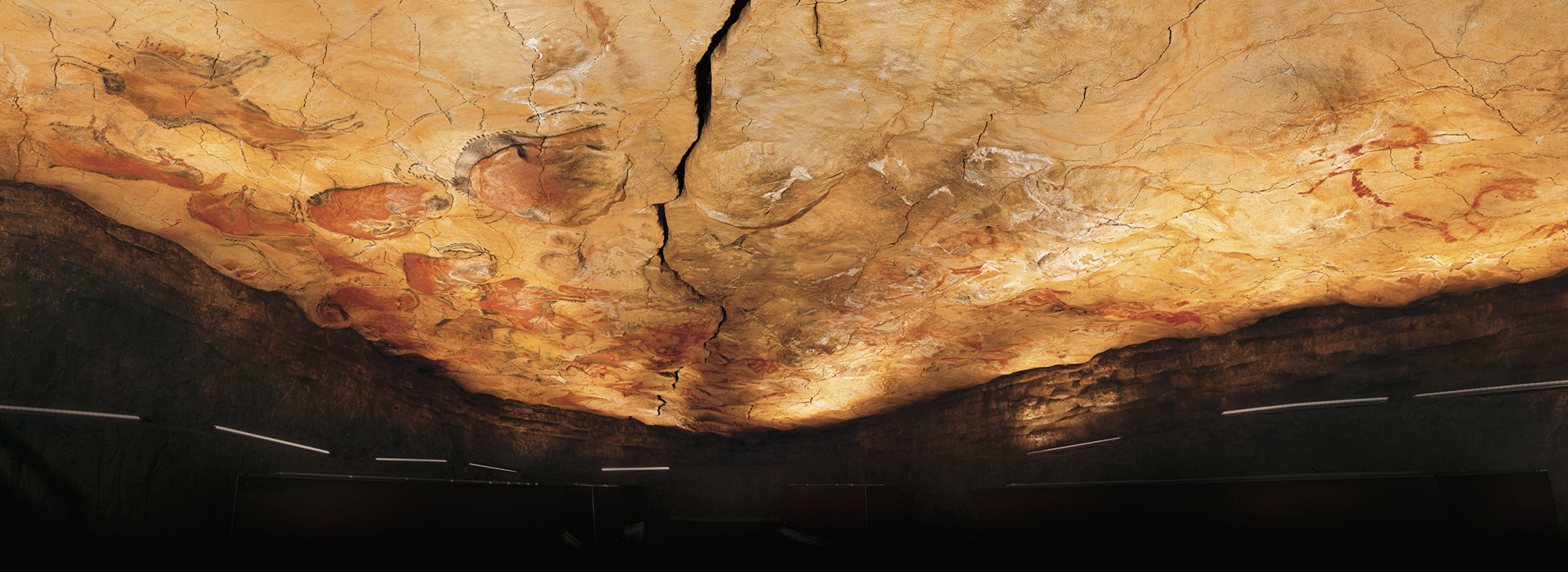

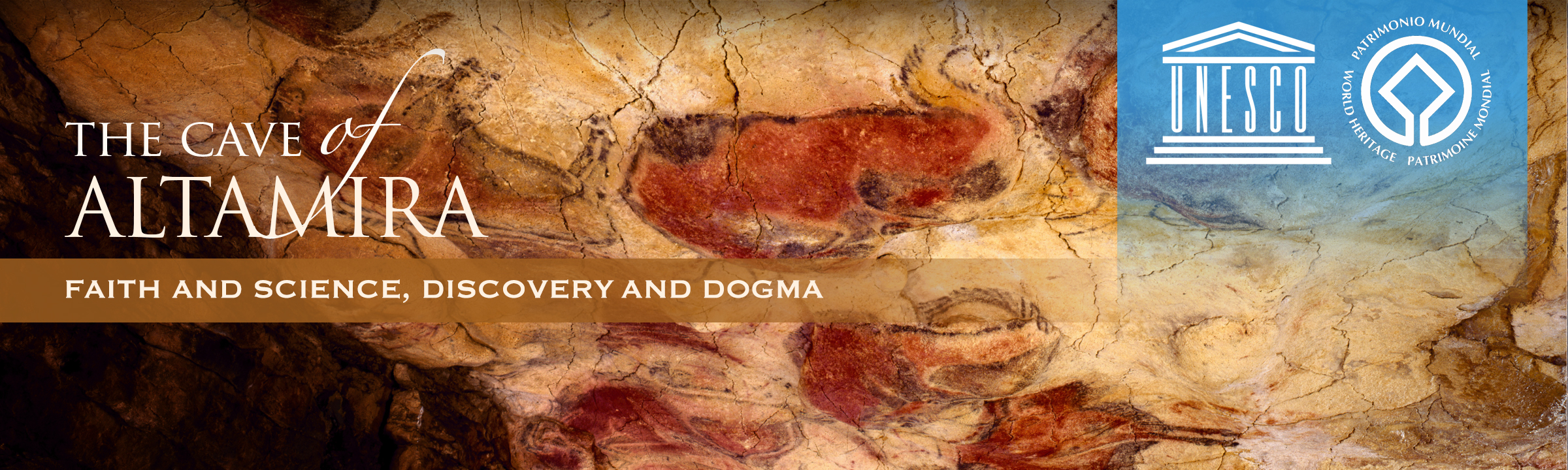

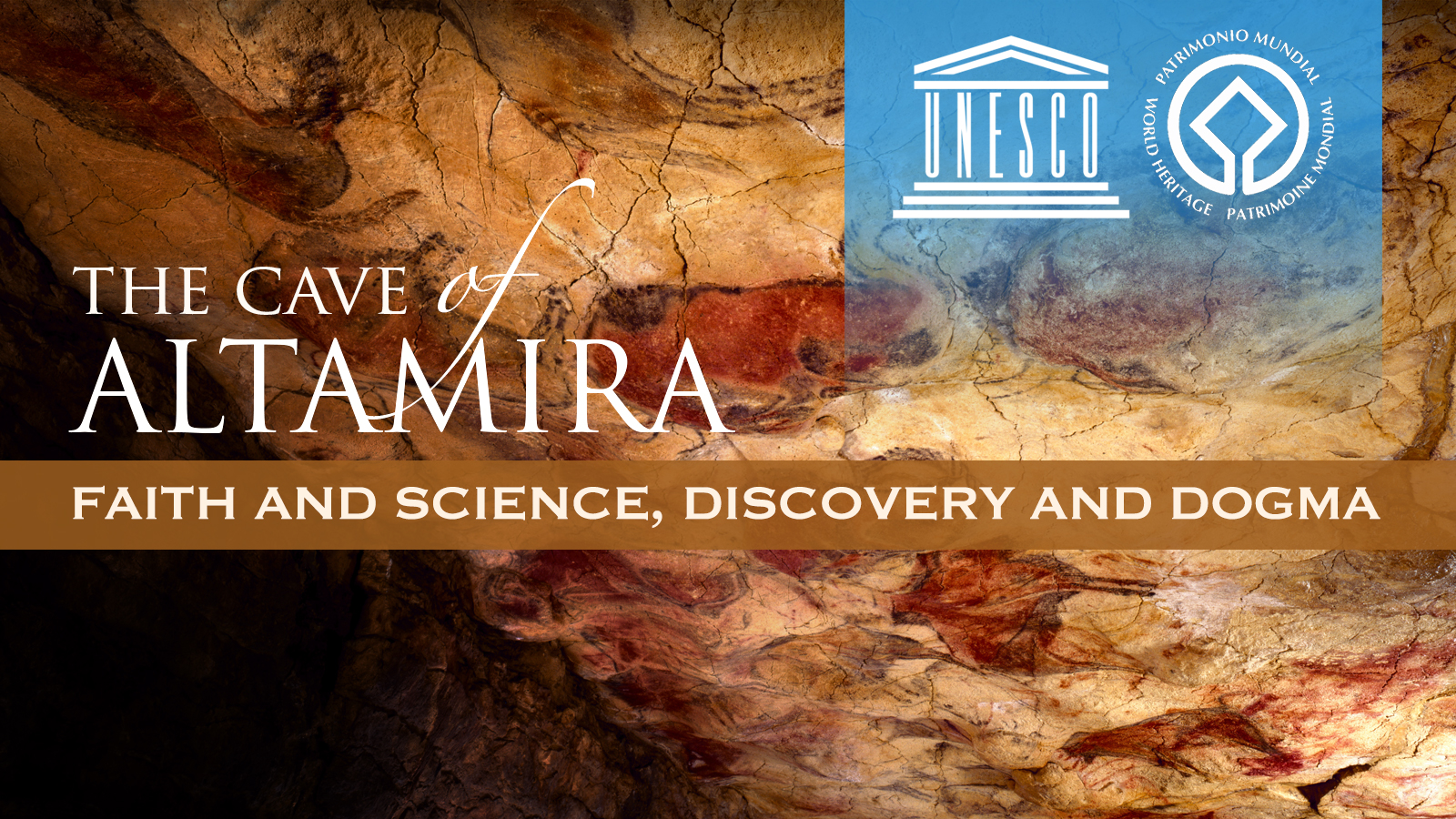

Whilst human occupation only occurred at the cave mouth, the painting, drawing and engraving took place throughout the cave. The artists used ochre and charcoal. As with other Palaeolithic artists, they used the natural contours of the cave walls to enhance the polychrome depictions; the contours may have inspired a particular depiction, or the artists may have been using this technique to provide a 3-dimensional element to the art. The art of Altamira encompasses naturalism, abstraction and symbolism.

The paintings and engravings of Altamira were begun during the Aurignacian period, the first chapter of Upper Palaeolithic art in Europe. The art was created over a period of 20,000 years, between 35,559 and 15,204 cal BP. The cave was re-used repeatedly, with artists either respecting and avoiding existing depictions, or adding to them and using them in new figures. We are left with a spectacular Palaeolithic palimpsest. The art throughout the cave of Altamira is impressive, but on the ceiling of the Hall of the Paintings it becomes truly spectacular.

This is the main attraction and interest of Altamira. The 25 large polychrome figures depict bison, a hind and two horses. They are between 125 and 170cm in length, while the hind is 2 metres. The figures were produced by engraving and drawing the outlines. Greater detail was achieved by deeper engraving. Most of the figures were then filled with red paint obtained from ochre, although some were painted with yellow or brown paint, again obtained from ochre. In several figures, black pigment was used for shading. The use of colour to capture anatomy was highly selective; to separate the legs from the chest, the haunches from the belly, and so on.

The natural protuberances on the ceiling were employed for perspective and volume (No. 34, 35, 36, 39, 50). Cracks were also used to represent outlines (No. 34). This grand composition is completed with the large head of a horse (No. 41) with the figure of a foal (no. 46).

This is the oldest stage in the decoration of the main ceiling, with animals painted in red, engraved signs, hands and several series of dots. Eleven large (between 150 and 180cm in length) red figures, mostly horses, were originally dispersed across a large part of the ceiling. None of them include any relief or other natural forms of the ceiling.

Near the Hall of the Paintings a very narrow side-passage is decorated with red signs. One sign consists of four irregular ovals divided up internally. Another sign, 3 metres in length and formed by long red bands of parallel lines crossed by small transversal lines, is tucked under an inaccessible rock prominence.

All of the black figures in Altamira were drawn with charcoal. This has allowed some of them to be dated by AMS radiocarbon. The age - Lower Magdalenian - together with certain stylistic and technical uniformity (charcoal as the pigment and a linear style) suggests they are belong to the same ensemble, even though they were probably created at different times.

Themes in Magdalenian art are varied; horses, aurochs, bison, ibices, red deer stags and hinds, semi-human faces and signs.

There are only four aurochs in Altamira, but all with similar styles. On the main ceiling, a large bull measuring almost 3 metres in length is partially hidden under a polychrome bison. The outline of the forehead and the line of the belly follow natural cracks in the rock wall. The dorsal line is a wide charcoal band with numerous engraved marks.

For a depiction of a bison, a natural rock feature becomes the starting point for a composition - a strip of calcite marked in black acts as the horn.

A group of quadrilateral black signs in the final passage were carbon dated to the Lower Magdalenian (15,440 +/- 200 BP GifA-91185). Nearby, and using natural forms in the rock, human-like faces known as 'masks' were created with a minimal use of marks to suggest eyes, eyebrows and mouths.

Engraved representations are found throughout Altamira. The red deer is the species most often represented with this technique. One large group of engravings seem to belong to the same family.

The date of this monochrome bison (No. 16) is the most recent, based on carbon dating - 13,130 +/- 120 BP - and therefore represents the work of the last artists.

It displays an artistic style and manner of execution that has matured; a selective application of charcoal, a smudging of the charcoal to achieve shading.

With the collapse of the cave entrance soon after - and the impossibility of re-entering the cave - it is intriguing to wonder how this sacred space would have continued to evolve artistically.

Having been sealed due to a rock fall, the cave was rediscovered in 1868 by a local hunter. Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, a local resident who was an amateur archaeologist, heard of the discovery and visited the cave in 1875. In 1879 he began exploring the cave in earnest, having become inspired by a recent visit to the 1878 Universal Exhibition in Paris where he had seen exhibits from the Stone Age.

The timing here was important - the study of prehistory as a science was in its infancy, and many of the ideas based on the scientific evidence were considered controversial by a society entrenched in rigid religious beliefs. To push the creation of art further and further back in time was meeting fierce scepticism on two fronts.

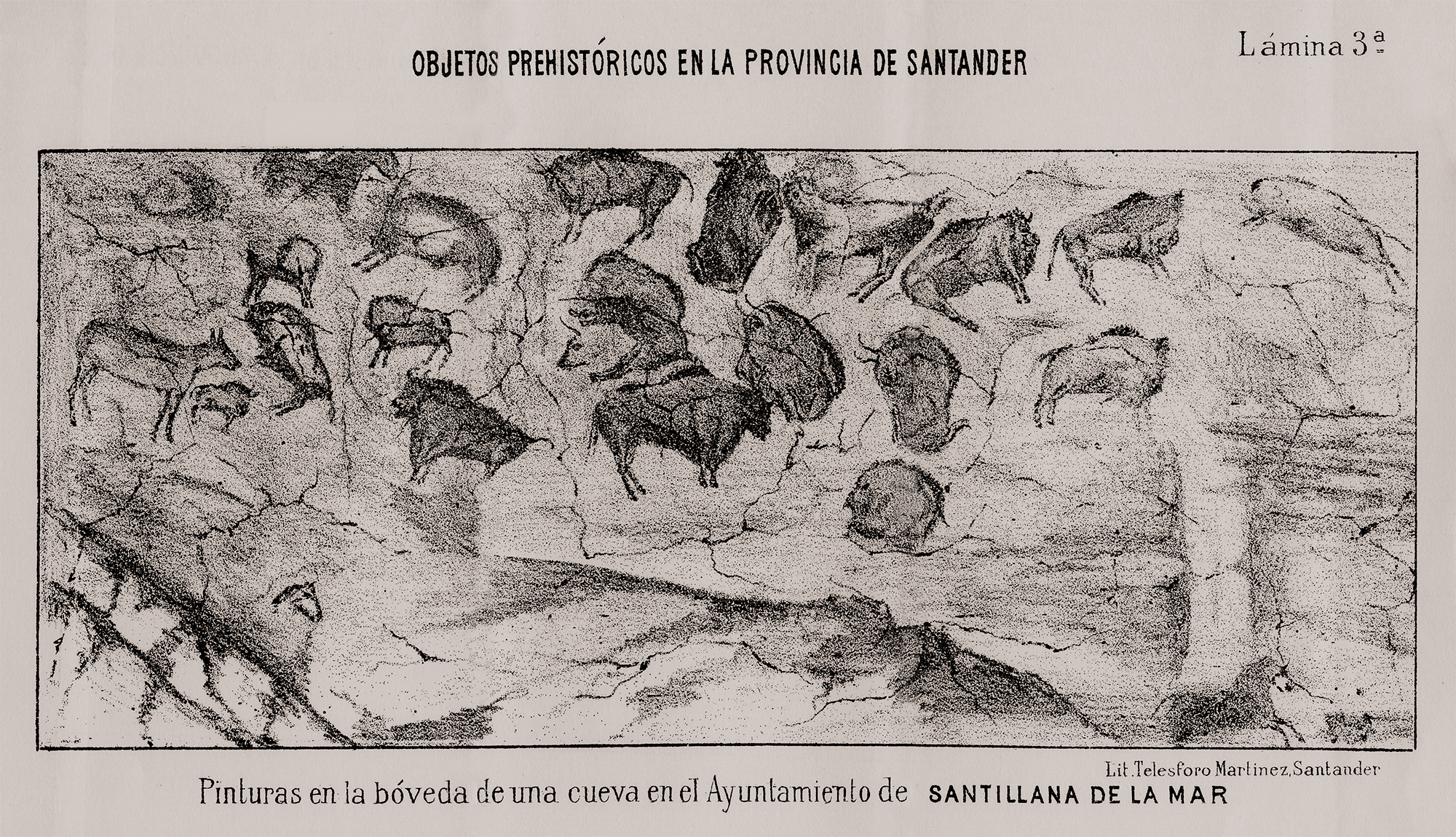

Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, however, felt certain that the paintings were from the Palaeolithic. In 1880 he published 'Breves apuntes sobre algunos objetos prehistóricos de la provincia de Santander' - 'Brief notes about a few prehistoric finds in Santander Province'.

Public humiliation for Sautuola followed. It was not until 1902, when several other findings of prehistoric paintings had served to render the hypothesis of the extreme antiquity of the Altamira paintings less shocking (and forgery less likely), that the scientific society retracted the opposition to Sautuola's suggestion. That year, the leading French archaeologist Emile Cartailhac, who had been one of the leading critics, emphatically admitted his mistake in the famous article, 'Mea culpa d'un sceptique', published in the journal L'Anthropologie.

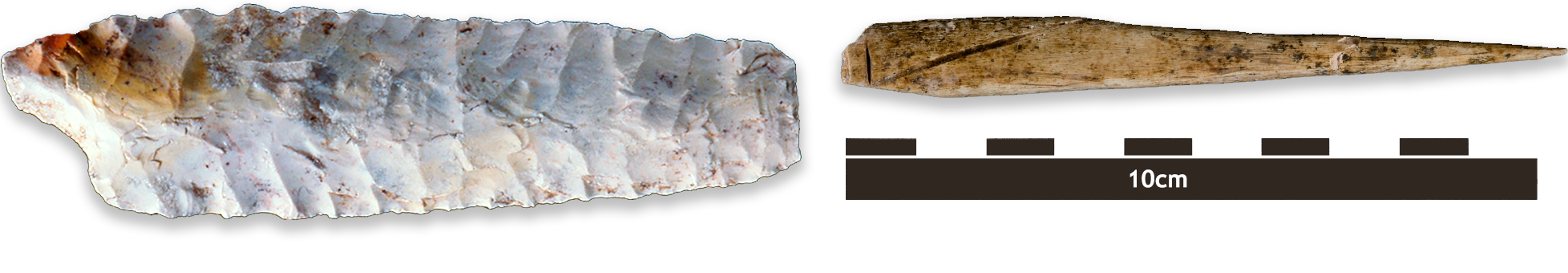

Objects found by Sautuola in the cave of Altamira © Museo de Altamira, Photo P. Saura.

Tragically, this vindication was too late for Sautuola, who had died 14 years earlier. It was only then that his proposal was considered pivotal. The cave of Altamira was the first place in the world where the existence of rock art from the Upper Palaeolithic age was identified.

Its uniqueness and quality, the stunning conservation, and the freshness of its pigments meant its acceptance would be delayed by a quarter of a century. At the time, it was a scientific anomaly, a discovery that constituted a giant leap and not an incremental step, and the phenomenon was difficult to understand for the society of the nineteenth century, gripped by extremely rigid propositions.

These airbrushes had gone unnoticed because they were initially catalogued as pendants by Hermilio Alcalde del Río.

The airbrushes were made from three segments of bones from the leg or wing of a large bird (a raptor or a wading bird). They display de-fleshing and cut marks in the form of transverse grooves. Two of the pieces are now understood to fit together because they are part of the same bone.

Because they exhibit traces of pigment on both outer and inner surfaces, researchers believe them to be tools used to apply red liquid paint. The bone pieces would have been placed at right angles to each other; by blowing through one section, the other section would absorb the paint and spray it outwards.

Alcalde del Río found these artefacts in crevices in the cave passage, and thus the lack of further stratigraphic context prevents any precise dating at this time.

Red deer scapula with two finely-engraved superimposed heads of hinds

In 2008-2009, an excavation was conducted in the modern entrance of the cave to determine whether part of the archaeological deposit existed in the area that is now outside the entrance beneath the collapse that blocked it. The end of an archaeological level measuring 20cm thick was located in the outer limit of the collapse, preserved from the erosive processes that had removed the level in the area next to it. It yielded numerous shells, faunal remains, lithic and bone objects, and a red deer scapula with two finely-engraved superimposed heads of hinds.

This type of engraving is of the same type as those found by Alcalde del Río from 1903 to 1905. The three dates for this level under the collapse place it between 15,370 +/- 60 and 15,610 +/- 80 BP, coinciding with Levels 2 to 4 in the interior deposit, in the Lower Magdalenian.

These dates refer to a very precise time, and are of special interest for Altamira as they make the striated engravings of hinds in the cave passages contemporaneous with the polychrome bison on the ceiling in the Hall of the Paintings. It is not possible to determine in which order the two kinds of depictions were produced.

By Pilar Fatás Monforte, Directora, Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira

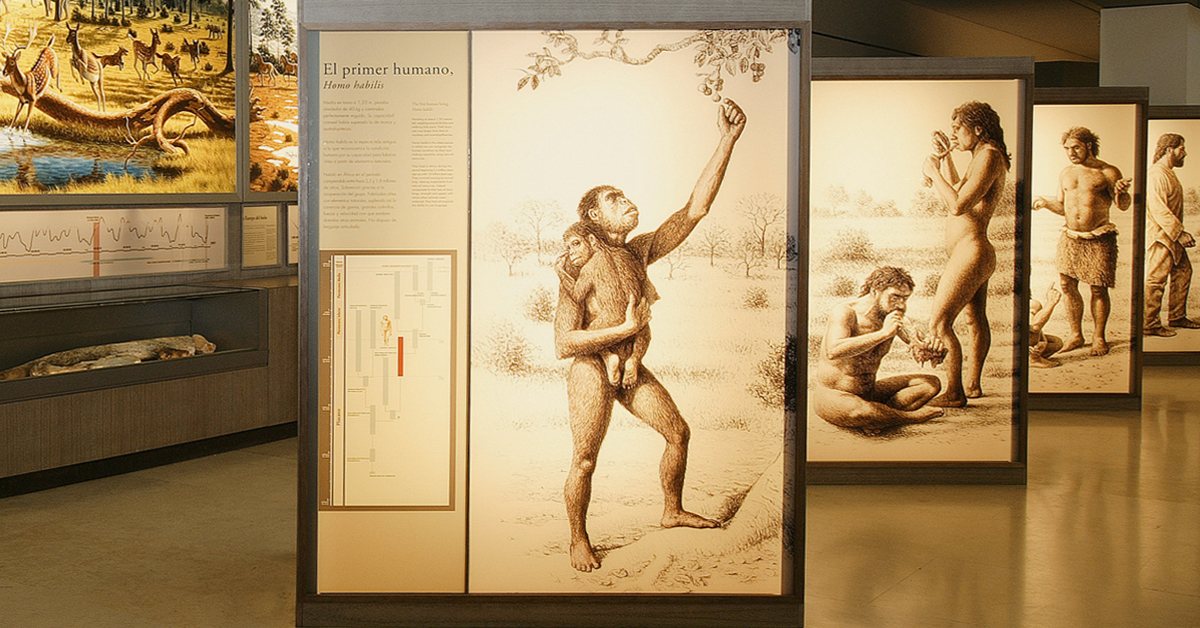

The Museum of Altamira is a place devoted to learning about, enjoying and experiencing the life of those who painted and inhabited the cave of Altamira. The museum's most attractive offer is the possibility of knowing the humanity's first art, Paleolithic art.

The Museum is in charge of a legacy of maximum value, the cave of Altamira, a milestone in universal art history which discovery meant the discovery of Palaeolithic cave art and one of its most spectacular manifestations. The showiness of the artistic expression of the cave's inhabitants was recognised by UNESCO, which in 1985 registered it on the World Heritage List.

The reproduction of the cave, the Neocave, presents Altamira as a Palaeolithic venue, a habitation site and a sanctuary. This meticulous and exact reproduction, made in full scale, reconstructs the cave of Altamira as it was between 22,000 and 13,000 years ago, when it was inhabited by groups of hunter gatherers. The remains of the everyday life of its inhabitants can be found in the hall area, where there are large collections of fauna, shells, charcoals, and utensils made out of flint stone, antler and bone, as well as the remains of pigments and objects of furniture that provide information about their way of life.

The art surprises the visitor, specially the colorful roof with its bison, horses, deer, goats, and painted and engraved symbols. It is in this part of the cave, scarcely penetrated by daylight, where the spaces of ritual and myth begin. This collection of animals and symbols represents a worldview, the spirituality of the hunters of the Upper Palaeolithic age and the start of our history.

The art of Altamira stands out on account of the quality of its paintings and engravings, as well as for the diversity of techniques and styles, and the collection of art spanning a period of more than twenty thousand years. It is the most spectacular embodiment of cave art and constitutes the masterpiece of brilliant painters.

'The Times of Altamira' was a research program initiated by the Museum in 2003 to thoroughly examine the archaeology of Altamira, both inside and out. The program succeeded in reconstructing the history of the cave and consolidating the documentation of its artefact collections. Consequently, research on the archaeological deposit and new dates for the art has contributed towards a new understanding of the Cave of Altamira.

Of the many artefacts discovered, two in particular merit attention. A Solutrean and spear point from the cave of Altamira © Museo de Altamira, Photo P. Saura.

The permanent exhibition 'The times of Altamira' gives visitors a closer look at the prehistoric era of the Iberian Peninsula. Different aspects of prehistoric life in Altamira are shown: art, culture, life, etc.

The life of the hunters and gatherers of the Upper Palaeolithic age is revealed through the archaeological objects on display, which take into account their original context and show how they were used and created.

Hunters and gatherers satisfied their requirements for survival by selecting natural resources through hunting, fishing and gathering. Part of their daily routine took place inside the caves, around the fire. Visitors can find out about their diet, the preparation of skins for making clothes and personal ornaments, the organization of the society and its relationship to its surroundings, the economics of exploiting the surrounding environment, seasonal movement throughout the land, and the main archaeological sites in Cantabria.

At the Museum of Altamira - Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira - located beside the Cave of Altamira, the group was hosted by the museum's Director Pilar Fatás, herself a member of the Rock Art Network.

The Museum of Altamira is a splendidly designed building devoted to learning of, enjoying and experiencing the life of those who painted and inhabited the cave of Altamira. The reproduction of the cave - the Neocave - presents Altamira as a Palaeolithic venue, a habitation site and a sanctuary. This meticulous and exact reproduction, made in full scale, reconstructs the cave of Altamira as it was between 22,000 and 13,000 years ago, when it was inhabited by groups of hunter-gatherers. The remains of everyday life of its inhabitants can be found in the museum's exhibition area, where there are large collections of fauna, shells, charcoals, and utensils made out of flint stone, antler and bone, as well as the remains of pigments and objects of furniture that provide information about their way of life.

'Color and power: rock art of San hunter gatherers in Ukhahlamba-Drakensberg'. The visit coincided with the new exhibition at the Museum of Altamira, displaying images of the cave paintings of Ukhahlamba-Drakensberg - which has the greatest concentration of this type of art - as well as objects of the San material culture. The exhibition is the result of collaboration between 2 members of the Rock Art Network, our host Pilar Fatás and Aron Mazel, archaeologist and researcher at the University of Newcastle in Britain.