An article by Alex Easton on abc.net.au - Ancient rock art at Carnarvon Gorge destroyed after walkway explodes in bushfire - reports on the ancient rock art that was destroyed after a recycled-plastic walkway intended to protect the site exploded during a bushfire in Carnarvon National Park, Australia.

Experts have assessed the site, containing rock art dating back thouands of years, and say it cannot be restored. The incident has prompted an archaeologist working with local Indigenous people to call for the removal of all flammable structures at vulnerable sites around the country. Similar walkways have since been removed across Queensland.

The destruction at Baloon Cave occurred during 2018's devastating Queensland bushfires, but has not been spoken about publicly until now to allow the site's custodians time to come to terms with the loss. While some of the hand stencils at the cave were ancient, other more recent stencils had been added over time. Baloon Cave working group member Dale Harding said the art was part of an ongoing cultural work that provided a link between his Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal ancestors over millennia and their descendants today.

Dale Harding explains "So what does it mean in the community? It's the foundation and the basis of who I identify as and who my family, my community — we all connect back to that. My elders describe the rock art panels, but also the whole network, as being a cathedral, a university, a hospital. All of these kinds of things come into that depending on who you are and how you have access to the knowledge that's contained in those cultural sites." Indeed, for the Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal people, the loss of the art, Mr Harding said, was akin to the destruction of Notre Dame Cathedral for the people of Paris. "We've lost one of the key sites of our cultural story."

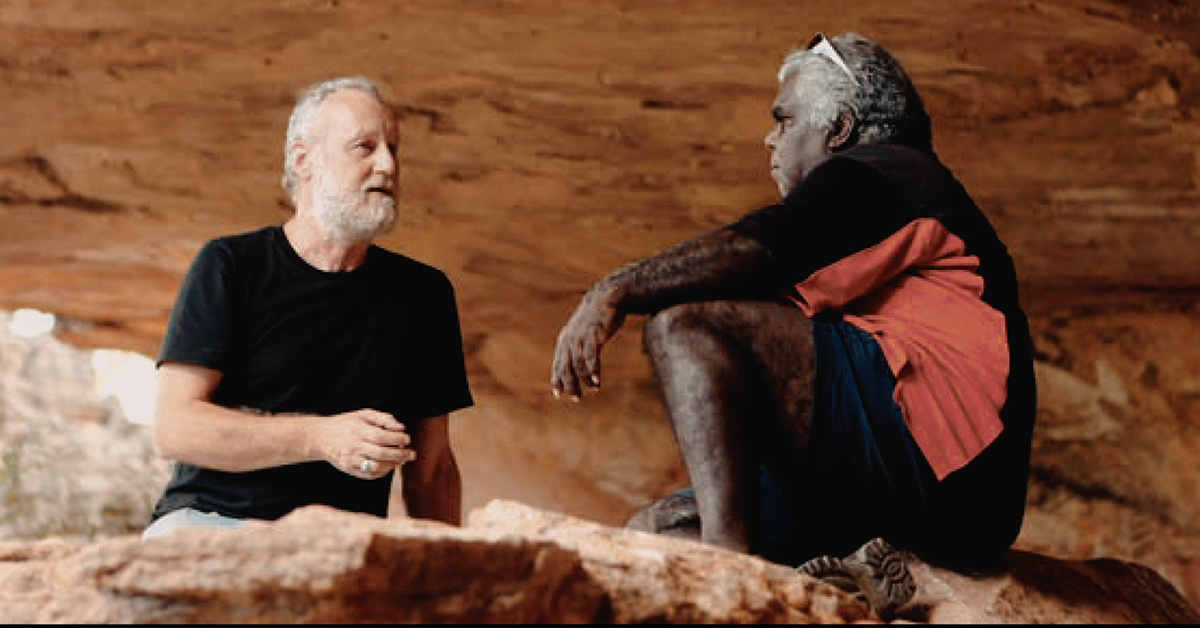

Griffith University archaeology and anthropology professor Paul Taçon said the destruction would not have occurred were it not for the placement of the recycled-plastic walkway; "Unfortunately, that's sort of like solidified petroleum, and if you have a hot fire underneath it, it melts and then it just explodes into a ball of flame and that's exactly what happened."

Smoke from the fire blackened the cave and parts of the rock sloughed off, taking hand stencils with it. A chunk of rock from a set of hafted stone axes high on the wall broke away; what's left now has a large crack through it. Mr Harding said the cave also suffered water damage from steam released from the plastic boards as they burned; "I've been witness to other sites which have not had a fuel load constructed immediately in front of them," he said. "And natural fire, bushfire, part of ... the cultural story on the landscape, has been and gone with very little impact, even very little noticeable trace."

Professor Tacon said a fire at Keep River in the Northern Territory hit another recycled-plastic walkway in 2008, setting off a fireball that sent paintings and engravings in a natural archway crumbling to the ground; "Unfortunately, although everyone wanted to get the word out then some things were published, it appears that people have forgotten that this stuff is really dangerous. So we need to make sure, and indeed the Aboriginal community wants to make sure, that no-one ever uses this in a rock shelter with art again."

Professor Tacon said that new sense of caution had to go beyond plastic walkways to include wooden structures, which he said had also burned and damaged Indigenous sites in NSW and the ACT. He explains that the "best thing is a non-destructive platform, something made out of steel for instance, or concrete and steel."

Environment Minister Leeanne Enoch, who is a Quandamooka woman from North Stradbroke Island, said the message about plastic platforms had been heard and communicated to her counterparts around the country; "I, personally, was absolutely devastated. I went and visited the site not long after hearing about what had happened. I know how significant these sites are and, for me personally, I felt every bit of the pain that everybody else felt and there was a lot of tears shed that day." Her department has since audited other cultural heritage sites around Queensland for structures similar to the plastic boardwalk and had them removed.

For the Bidjara, Ghungalu, and Garingbal people, Mr Harding said they wanted the broader community to recognise and understand the grief, trauma and state of crisis they were facing. They also wanted other Indigenous people with a connection to the cave to join the conversation about the site and what had happened there. "If this is your story, if you are connected, you do have family lineage back to Carnarvon Gorge, whether that's through Bidjara ... or all the other groups which that water flows through, I'd encourage, as we are trying to do in our networks, have the conversations, ask who are those people who are the representatives or the older ones who might be able to shed light on that and then move out from there. There is an ongoing conversation and the more people we have, the more Murris we have involved in representing that story in the best way possible, the better we'll be able to move out of this, this reality with Baloon Cave."

click here to hear the ABC radio Queensland live interview with Professor Paul Taçon

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 09 August 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 24 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 04 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 01 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 20 March 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 13 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 13 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 01 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 28 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 23 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 31 October 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 October 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 20 September 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 09 August 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 24 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 04 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 01 July 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 20 March 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 13 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 13 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 01 February 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 28 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 23 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 31 October 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 October 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 20 September 2023

Friend of the Foundation