George H. Nash

Nash@Liverpool.ac.uk

Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, University of Liverpool, UK

CGeo - Centro de Geociências da Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, 3030-790, Portugal

George H. Nash

Nash@Liverpool.ac.uk

Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology, University of Liverpool, UK

CGeo - Centro de Geociências da Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, 3030-790, Portugal

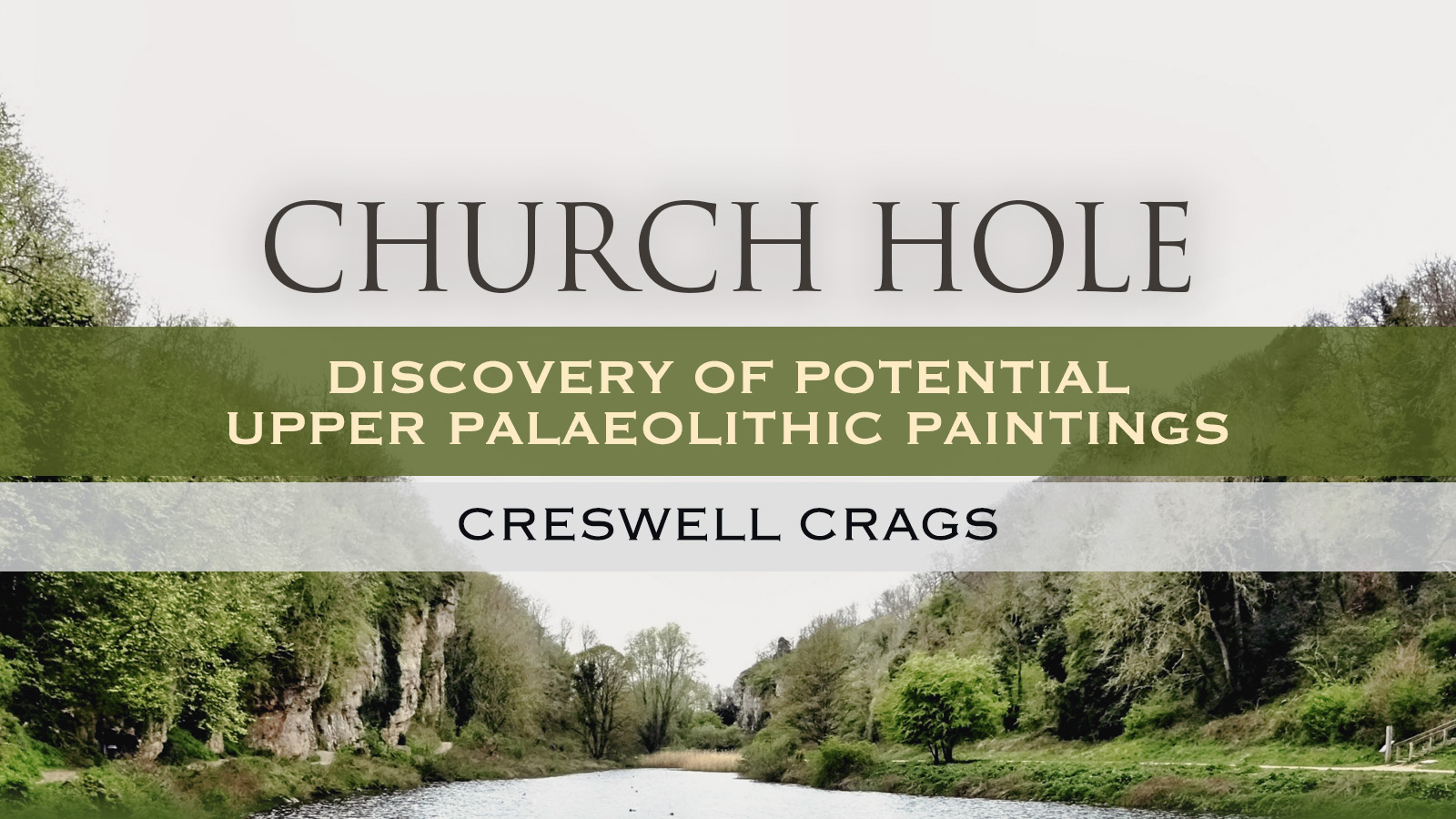

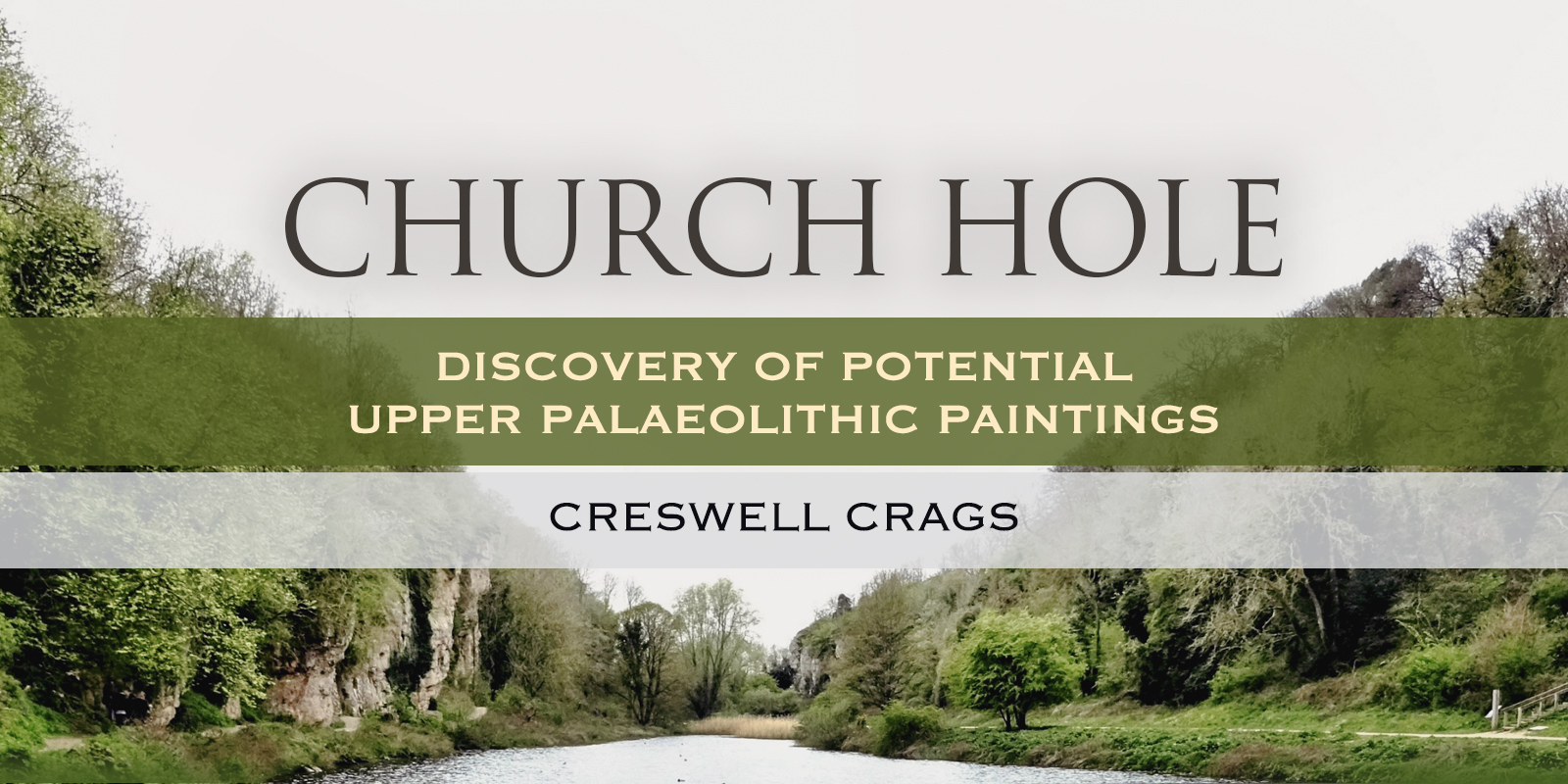

This article explores the recent discovery and documentation of previously unrecorded painted imagery within Church Hole, a cave situated in Creswell Crags—a limestone gorge in Nottinghamshire, in the northern Midlands of England, known for its evidence of Late Upper Palaeolithic activity. The new findings, made in 2021 and 2024, build upon a significant earlier discovery by an Anglo-Spanish research team in 2003, which identified the first verifiable examples of engraved Upper Palaeolithic rock art in the British Isles. That earlier discovery comprised both figurative engravings and simple geometric motifs. Notably, several of these engraved panels were partially covered by calcite flowstone, which was dated to the Late Upper Palaeolithic (approximately 13,000 years before present) using Uranium-Thorium (U-Th) dating techniques.

At present, the newly identified painted images (identified as Panels A to F )—like the majority of engraved motifs recorded in 2003—cannot be directly dated using chronometric methods, due to the absence of calcite flowstone overlaying the painted surfaces.

In 2021, the author initiated a research project in collaboration with the Creswell Crags Museum, aimed at conducting a detailed survey of Church Hole to identify potential painted imagery. The project utilised photogrammetric techniques in combination with a desk-based colour-enhancement algorithm, Decorrelation Stretch (D-Stretch), to facilitate the detection of painted motifs. Upon completion of the survey, the cave was systematically mapped using high-resolution point-cloud capture technology. The full results of these investigations are scheduled for publication in late summer (Nash, Beardsley & Herrod, 2025).

Creswell Crags is a naturally formed gorge incised into magnesian limestone, centred at National Grid Reference SK 53350 74262. It straddles the boundary between the counties of Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. The gorge comprises more than twenty natural caves, rock shelters, and overhangs, nine of which have been subject to archaeological investigation since the mid-nineteenth century (Bahn & Pettitt 2009).

This article presents the results of a photogrammetric survey undertaken at Church Hole, located on the southern side of the gorge (NGR SK 53380 74109). The survey was conducted in two phases: 18–19 June 2021 and 16 April 2024. The outcomes of these surveys are discussed in detail below. Earlier surveys conducted in 2003 focused on the identification of engraved Upper Palaeolithic rock art (Pettitt et al. 2007; Bahn & Pettitt 2009). These engravings were subsequently dated using chronometric techniques (Pike et al. 2005; Pike et al. 2009). At the time of their discovery, the Creswell Crags assemblage was considered the earliest confirmed example of rock art in the British Isles.

Creswell Crags constitutes a site of considerable archaeological importance, situated within the Limestone Heritage Area, which also encompasses eleven additional vales, gorges, and grips (Davies et al. 2004). The site has been designated both a geological Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and a Scheduled Monument (NHLE 1006384). It lies within the Welbeck Estate, which includes the Creswell Crags Museum and Heritage Centre, as well as surrounding woodlands that function as a key destination for tourism and education.

According to the Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire Historic Environment Records (HERs), Creswell Crags is primarily characterised as a Palaeolithic site. However, archaeological evidence from various locations within the gorge indicates occupation or activity spanning later periods, including the Mesolithic, Neolithic, Roman, Medieval, and post-medieval eras. The site is especially renowned for its Middle and Upper Palaeolithic archaeological record and sedimentary deposits, most notably within the caves of the gorge. On the northern (Derbyshire) side, prominent cave sites include Mother Grundy’s Parlour, Robin Hood’s Cave, and Pin Hole Cave. On the southern (Nottinghamshire) side, key sites include Church Hole and Boat House Cave (see Figure 1).

Despite extensive disturbance resulting from post-medieval landscaping activities undertaken by the Bentinck family and the Duke of Portland, substantial areas of the gorge continue to preserve early prehistoric deposits. The landscape of the Welbeck Abbey Estate, into which the gorge is integrated, has been designated as a Grade II Registered Park and Garden (List Entry 1000556). During the early 18th century, this landscape was modified through the planting of native and exotic tree species, the construction of ornamental shrubbery beds, and the deliberate flooding of the gorge floor to create a lake—part of a broader water management system (see Figure 2). At the same time, limestone cliffs along the gorge were quarried for building stone.

Archaeological investigations at Creswell Crags began in the 1850s and have continued intermittently through the 1920s to the 1980s, with a renewed phase of research in the early 2000s. The cumulative body of work has been extensively synthesised in major publications, notably by Jenkinson (1984), Pettitt et al. (2012), and Pettitt and White (2012). As a result of these decades of study, Creswell Crags is widely regarded as “Britain's primary resource for the archaeology and palaeontology of the later Upper Pleistocene” (Pettitt et al., 2012). The site represents one of the largest and most significant concentrations of Upper Palaeolithic archaeological deposits in Britain.

While Creswell Crags is the most prominent of such complexes, four additional major clusters of Upper Palaeolithic activity have been identified south of the Devensian glacial limit: the Gower Peninsula, the Mendip Hills, the Wye Valley Gorge, and the Jurassic Coast (stretching from Hengistbury Head to Kent’s Cavern). These regions, together with Creswell, form a critical network for understanding human adaptation and occupation during the Late Pleistocene in north-western Europe.

The extensive archaeological record at Creswell Crags has yielded a robust dataset for subsequent research (Davies et al., 2004). However, interpretive challenges persist, primarily due to gaps in early documentation, inconsistencies in stratigraphic recording, and the dispersal of artefactual material across numerous institutions in the UK and abroad. These limitations have, at times, led to inaccurate or outdated assumptions regarding the site’s occupational history. Nevertheless, Creswell Crags remains central to our understanding of Neanderthal and anatomically modern human activity at the northern edge of habitable Europe during the later Pleistocene (ca. 50–10 kyr BP)—a marginal zone often referred to as the ‘Northern Frontier’ (Ashton et al., 2010; Pettitt and White, 2012).

Over the course of 150 years, the quality of excavation methodologies has varied considerably. Many early excavations lacked rigorous stratigraphic control and detailed record-keeping, making it difficult to correlate findings across excavation seasons or between different areas of the site. Furthermore, the dating of archaeological materials has frequently proven problematic due to both the limitations of early chronometric methods and post-depositional disturbances.

Several initiatives have sought to address these issues. The Ancient Human Occupation of Britain (AHOB) project (Ashton et al., 2010), the comprehensive assessment of the dispersed Creswell collections (Wall and Jacobi, 2000), and targeted excavations at the Church Hole entrance (Pettitt et al., 2007) have all contributed to clarifying the archaeological sequence and its broader implications. These efforts have also emphasised the untapped potential for further material recovery within the Creswell Gorge, particularly through the application of modern analytical techniques.

During the course of the current photographic and contextual survey, it was observed that a significant amount of sediment had been removed from beneath the original cave floor at Church Hole. Only the rear portion of the cave appears to retain its original depositional surface.

In 2003, an Anglo-Spanish research team discovered a series of Upper Palaeolithic engravings within Church Hole, identifying approximately 16 motifs concentrated in the central and northern sectors of the cave, just south of the present-day entrance (Ripoll & Muñoz, 2007; Bahn & Pettitt, 2009). These engravings predominantly depict Late Pleistocene megafauna, aligning stylistically and thematically with other known Upper Palaeolithic art sites across western Europe.

To resolve debates regarding the authenticity and chronology of these features, areas where stalagmitic calcite was observed to overlay the engravings were subjected to Uranium-Thorium dating (Pike et al., 2005). While this constituted a significant advance in the site’s interpretive framework, the possibility of painted rock art has been largely overlooked in subsequent investigations—despite evidence from other Upper Palaeolithic contexts suggesting that engravings and paintings often co-occur.

In 2021 and again in 2024, the author conducted preliminary surveys of several cave sites within Creswell Gorge—most notably Church Hole and Robin Hood’s Cave—specifically aimed at identifying traces of painted prehistoric imagery. The findings, which were promptly communicated to the Creswell Heritage Trust, suggest the presence of several painted motifs. These include both animal figures and geometric designs, some of which overlap with or lie beneath the engraved imagery documented in 2003. Crucially, although haematite-rich deposits naturally occur within the exposed cave walls, the author was able to distinguish between these and iron oxide pigments that had been intentionally applied by human agency, based on texture, distribution, and contextual association. These observations suggest that painted art was probably a part of the Upper Palaeolithic symbolic repertoire at Creswell Crags, warranting further detailed investigation using non-invasive imaging and pigment analysis. The sites identified in the 2021 and 2024 surveys were subsequently plotted on a 3D can of the cave (Figure 3).

| The stratigraphic units are described as follows: | ||

| 1 | Breccia | A calcite-rich deposit forming the original floor level between Panel B and extending approximately 3–4 meters to the south, with remnants of this floor continuing beyond Panel C. |

| 2 | Cave-Earth A | A lens of substrate located beneath the breccia layer. |

| 3 | Cave-Earth B | A deposit with an approximate thickness of 0.75 meters, extending northward from beyond Panel B to Panel E. |

| 4 | Mottled Bed Substrate | A stratigraphic layer overlain by the cave-earth deposits, extending north from beyond Panel B to Panel C. |

| 5 | Red Sand Deposit | This layer extends from beyond Panel B to Panel E and is approximately 1.1 meters thick. |

| 6 | White Sand Deposit | A thin lens of white sand lying beneath the red sand layer and extending below the current floor level from Panel B to Panel F. It is about 0.3 meters thick and likely associated with late Middle Palaeolithic activity. |

| 7 | Bedrock | The base layer composed of grey to buff-grey dolostone, a type of carbonate rock. |

This stratigraphy provides valuable context for understanding both the palaeoenvironmental and archaeological conditions that shaped human activity within the cave, as well as in the locality during the latter part of the Pleistocene.

The identification of Upper Palaeolithic imagery at Creswell Crags offers significant opportunities for advancing research, especially with the discovery of Palaeolithic rock art that includes both engravings and now, potential painted imagery. The engraved rock art, initially identified by the Anglo-Spanish team in 2003, represents a key asset for further study.

The photogrammetric survey conducted in June 2021 initially identified nine panels with probable painted imagery, and an additional two panels were discovered in the April 2024 survey. Notably, three engraved panels—depicting red deer, bovines, and wild fowl/cervids (labelled Panels A, B, and C)—appear to have been largely painted previous to the engravings. These painted images, which are not visible to the naked eye, were analysed using the Decorrelation-Stretch (D-Stretch) algorithm (e.g., Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Photogrammetric surveys of Church Hole were undertaken in June 2021 and April 2024. The results of the 2021 survey were shared with the Creswell Heritage Trust and the Inspector of Ancient Monuments at Historic England. These investigations revealed painted motifs, most likely created using locally sourced haematite (iron oxide), although the precise dating of these motifs remains unresolved. While the 2021 survey was non-systematic in nature, it employed rigorous, non-invasive methodologies that yielded valuable insights, identifying several panels of interest, including Panels A to F.

Given the fragile nature of the cave’s surface geology, no measuring scales were placed in direct contact with the cave walls, except where natural ledges permitted. Where feasible, painted surfaces were approximately measured using a hand-held measuring tape.

The survey utilised high-resolution digital photography under blue (cold) light, avoiding the use of flash. All images exceeded 5 MB in size. Although the pigments were significantly faded and largely invisible to the naked eye, the application of the DStretch algorithm enhanced the visibility of these features (Figures 4 and 5). Developed by Jon Harman in 1995 and originally implemented by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory as a remote sensing GIS tool, DStretch is designed to manipulate RGB matrices in digital imagery. It has proven particularly effective in isolating pigment-based features, such as red, yellow, and black, facilitating the distinction between natural mineral staining and anthropogenic haematite applications. Through the application of DStretch, at least six potential painted panels were identified across the two survey phases.

Initially, the identified panels were georeferenced relative to the cave’s entrance grille, based on the cave plan published by Jacobi (2007). However, in late 2024, Terra Measurement Ltd provided a fully rendered 3D point cloud model of the cave, incorporating detailed surveying, georeferencing, and digitisation processes. This animated 3D rendering enabled the accurate spatial plotting of the newly identified features throughout Church Hole (see Figure 3).

For this article, the author has produced two side-by-side images which shows the same frame. The left-hand frame is the raw image, as taken during the survey of the cave. The right-hand frame is the colour filter manipulated image showing the D-Stretch image, used for specific colour enhancement (i.e., varying hues of red).

Many of the newly identified panels were partially obscured by both historical and modern graffiti. Panels A to C display engraved imagery, with indications of underlying painted surfaces. These include a cervid (likely a red deer) on Panel A, a bison on Panel B, and what appear to be a bird and a long-necked cervid on Panel C. The engravings from these panels—as well as others within the cave—have been extensively discussed in earlier publications (e.g., Ripoll & Muñoz 2007; Bahn & Pettitt 2009).

Panel A: The engraved red deer, probably first discovered sometime during the mid- to latter part of the 20th century (Bahn & Pettitt 2009) and re-identified in 2003, measures 0.68 m by 0.58 m and is accompanied by historic and modern graffiti. The engraved outline of the deer is clearly visible, despite the addition of a straggly beard that was added by a visitor at some time during the mid- to latter part of the 20th century. A calcite flow covering the lower section of the panel contains notches that were dated to a minimum age of 13.1 kyr (Pike et al. 2009) (Figure 6). These notches, numbering seven short vertical lines were beneath the hind leg of the deer.

Panel B: The bison engraving (Figures 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14), measuring approximately 0.45 m in length by 0.30 m in height, is associated with a spread of haematite visible along the legs and central torso of the figure. This spread is likely the result of multiple painting episodes, possibly incorporating earlier motifs into the animal’s form prior to its subsequent engraving. The stylistic characteristics of the bison are consistent with Upper Palaeolithic representations found elsewhere, particularly within the Franco-Cantabrian region of southwestern Europe.

Of particular note are the head and neck areas of the engraving, where the artist appears to have either made use of a natural haematite flow or deliberately painted within the engraved contours to accentuate these features (Figures 11 and 12).

However, an alternative interpretation is that the haematite distribution may be a natural mineral secretion, with the engraver either intentionally or inadvertently incorporating it into the composition. In this scenario, the engraved lines forming the legs of the bison appear to be deliberately aligned with the haematite spread (Figures 13 and 14). Regardless of its origin, the relationship between the engraving and the haematite is interpreted here as intentional—a manipulation of a natural geological feature to enhance the visual impact of the engraved image. This approach aligns with known practices among Upper Palaeolithic artists, who frequently integrated natural rock surface features into their compositions.

In the case of the Church Hole bison, the artist has also utilised the surface topography of the panel to further enhance the engraving. The lower leg sections terminate precisely at a wavy ridge in the lower portion of the panel, suggesting that this natural geological feature was used to imply a virtual ground surface (Figures 13 and 14). Such deliberate use of natural ridges to create spatial or compositional effects is relatively rare in Upper Palaeolithic rock art and may indicate a sophisticated level of visual planning within the panel’s execution.

Panel C: Located approximately 20 metres south of the cave entrance and positioned 0.5 metres above the original floor level, this panel contains engravings depicting two animal figures—interpreted as the head and neck of a cervid and a species of wildfowl, possibly from the Anatidae family. These engraved motifs are highly unusual within the context of Upper Palaeolithic art in northwestern Europe. However, stylistically comparable engravings—particularly emphasising elongated neck features—have been documented in Mesolithic contexts along the south and central coastal regions of Norway, dating to approximately 10,000–11,000 years before present (Nash 2008).

Notably, Panel C appears to have escaped the mining activity that affected the cave wall immediately to its north, closer to the entrance. While Panel C is characterised by a smooth, unaltered surface, the adjoining northern section exhibits signs of mechanical intervention, with jagged, hewn rock surfaces indicating that the cave walls in this area were likely widened during recent anthropogenic modification, presumably to improve access.

Digital enhancement using the DStretch algorithm revealed traces of what appears to be applied haematite, suggesting intentional pigment use and thus human agency in the creation of the artwork. Additionally, a black charcoal line was detected traversing parts of the panel, although its chronological relationship to the engravings remains undetermined (Figures 15, 16 , 17, 18 ).

Panel D: This panel is located within the central section of the cave. Of particular interest is the painted triangle, with a single short vertical painted line extending downwards from the apex. The image has been applied using finger dots in a linear fashion, forming three short lines, each measuring between 3 and 5 cm. Other faint painted imagery is present immediately north of the triangle, towards the entrance. This motif is common in Palaeolithic art and has traditionally been referred to as a pubic triangle (a term that I am not happy with) (Figure 19 & Figure 20).

Panel E: Is situated on the eastern wall at the rear of the cave, approximately 0.9 metres above the original cave floor, beyond a sump feature. This panel displays two clearly visible, though partially fragmented, painted ovoid motifs. Unlike most painted surfaces within Church Hole, these motifs are readily visible to the naked eye; however, their chronological placement remains undetermined.

Detailed visual analysis reveals that the pigment was applied as a thick, viscous paste, which was not fully absorbed into the rock substrate (Figures 21, 22, 23, 24). If these motifs are indeed of prehistoric origin, it is conceivable that they were intended to form a composite symbol resembling the letters ‘B’ or ‘R’. However, this interpretation remains speculative. Importantly, the motifs were created using a technique involving finger-dot impressions—sequential dabs forming both linear and curvilinear elements. If the motifs were of more recent origin, it is likely that a brush would have been used instead, and haematite would have been an unlikely pigment choice.

To determine the precise composition of the pigment, micro-sampling and geochemical analysis would be required—ideally through Raman spectroscopy. An application for Scheduled Monument Consent (SMC) will be submitted to Historic England, seeking permission to collect pigment samples from this and other haematite-marked areas of the cave where no previously documented Late Upper Palaeolithic engravings are present.

Although this rear area of the cave has been accessible since at least the mid-19th century, all known historic graffiti consists of engraved markings—primarily textual elements—produced using metal tools.

Panel F: Is located above the entrance to the sump at the rear of the cave. At its northern extent is a small dot measuring approximately 3 × 2 cm (Figures 25, 26, 27). This mark consists of a cluster of finger impressions—a motif commonly associated with Upper Palaeolithic cave art across Europe. The pigment appears to be applied haematite, rather than a naturally secreted deposit.

The positioning of the mark appears intentional and may have served as a visual cue or symbolic indicator, possibly denoting the transition into a more restricted or significant area of the cave. At this specific location, the original cave floor and the ceiling of the sump are separated by only a few centimetres. As such, access to the rear section of the cave, past Panel F would have required a tight crawl through a confined passage approximately 3–4 metres in length.

Creswell Crags, renowned for its heritage significance and palaeoenvironmental value, represents one of the most important early prehistoric sites in northern Europe, with evidence of human occupation dating from the latter part of the Middle Palaeolithic (c. 60,000–40,000 years BP). Of the approximately 20 caves, rock shelters, and overhangs in the locality, nine have been the subject of intensive archaeological investigation, particularly between 1870 and 1930. Although the archaeological techniques employed during this period were less advanced than those used today, early excavations by Mello (1875, 1876, 1877) and subsequently by Heath (1879) at Church Hole provided valuable baseline stratigraphic observations, particularly in the southern section of the cave.

A major archaeological challenge arises from the fact that these late 19th-century excavations removed most of the in-situ sediment from Church Hole. However, recent work, including a high-resolution 3D rendered plan of the cave (Nash, Beardsley & Herrod, 2025), has identified the original floor level preserved in the cave wall sections. This reconstruction allows for a more accurate understanding of the cave’s internal morphology and offers insight into the level of difficulty involved in accessing certain areas—particularly those where rock art is now known to exist.

The discovery of engraved rock art in 2003, in combination with earlier excavation work (e.g., Mello 1875, 1877; Heath 1879; Armstrong 1937, 1938), has firmly established Church Hole as the most significant decorated cave at Creswell Crags. It was also the site of the first faunal remains discovered in the area (in 1872) and yielded one of the most substantial lithic assemblages. Although no direct evidence of human activity was identified in the central chamber during earlier excavations, more recent surveys have revealed a rich corpus of engraved imagery—and now, possibly painted motifs as well.

It must be emphasised, however, that the present-day cave morphology likely differs significantly from that of the Upper Palaeolithic period. The current entrance, for instance, would have extended several metres further north during prehistory. Subsequent geomorphological processes—especially water percolation and freeze-thaw cycles—have caused significant erosion and recession of the cave entrance over millennia. This necessitates a reconsideration of the spatial context of the engraved and painted panels. Based on comparative research across Europe and the British Isles, Upper Palaeolithic cave art is rarely located near cave entrances, but instead tends to be situated in more discrete, internal areas of cave systems. It is therefore plausible that the engraved images of the red deer and bison, as well as associated painted motifs, were originally situated at a greater distance from the prehistoric entrance than they appear today.

A further point of interest concerns the historical accessibility of Church Hole. Although Mello (1875) provides one of the earliest published accounts of exploration, the presence of engraved graffiti in the southern section of the cave, located several metres beyond the sump, indicates access as early as 1860 (Figure 28). At the time this graffiti was created—and as later supported by Mello’s observations—entry into the cave’s central and rear sections would have been considerably constrained due to low ceilings and narrow passageways.

The photogrammetric surveys conducted in 2021 and 2024 identified six potential painted panels (Panels A to F) containing motifs created using applied haematite. These motifs include geometric shapes, painted infills associated with engravings, and finger-dot patterns—some isolated, others arranged in linear or curvilinear sequences. The painted imagery identified, particularly on Panels B and E, is consistent with known Upper Palaeolithic rock art traditions and exhibits stylistic parallels with comparable sites across continental Europe.

The presence of calcite accretions over several of the painted motifs provides valuable information regarding their relative antiquity. Application of Uranium-Thorium (U-Th) dating techniques to these calcite layers offers the potential to establish a more precise chronological framework for the paintings.

Given the extreme rarity of both portable and parietal Upper Palaeolithic art within the British Isles—with only two caves currently recognised as containing authenticated rock art (e.g., Bahn & Pettitt 2009; Nash et al. 2012)—these discoveries position Creswell Crags as a site of major significance for the study of early symbolic behaviour and artistic expression. The coexistence of historic and modern graffiti alongside prehistoric imagery further complicates the interpretive context, necessitating meticulous analytical approaches to distinguish later intrusions from the earliest manifestations of human visual culture within the cave.

The author extends sincere thanks to Creswell Heritage Trust for granting access to Church Hole and Robin Hood’s Cave, especially Angharad Jones, George Buchanan, and Paul Baker. Appreciation is also due to English Heritage (Tim Allen) and Nottinghamshire’s County Archaeologist Ursula Spence for their advice and support. Additionally, Richard Suckling and Elizabeth Poraj-Wilczynska of Cave Bear Films are thanked for their contribution, as well as the Bradshaw Foundation for their generous financial support.

A version of this article was published in early 2025

Armstrong, A.L., 1937. Report of Committee for the Archaeological Exploration of Derbyshire Caves, Interim Report 15. Report British Assoc. Adv. Science, Vol. CVII, 395.

Armstrong, A.L., 1938. Report of Committee for the Archaeological Exploration of Derbyshire Caves, Interim Report 16. Report British Assoc. Adv. Science, Section H.

Ashton, N.M., Lewis, S.G., Stringer, C.B., (eds) 2010. The Ancient Human Occupation of Britain. Developments in Quaternary Science, Vol. 14. Series editor, van der Meer, J.J.M. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Bahn, P. & Pettitt, P., 2009. Britain's Oldest Art: The Ice Age cave art of Creswell Crags. Historic England

Davies, G., Badcock, A., Mills, N., Smith, B., 2004. Creswell Crags Limestone Heritage Area Management Action Plan. ARCUS.

Heath, T., 1879. An abstract description and history of the bone caves of Creswell Crags. Derby: Wilkins & Ellis.

Jacobi, R.M., 2007. The Stone Age Archaeology of Church Hole, Creswell Crags, Nottinghamshire. In P. Pettitt, P. Bahn & S. Ripoll (eds.) Palaeolithic Cave Art at Creswell Crags in European Context. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 71-111.

Mello, J.M., 1875. On some Bone-Caves in Creswell Crags. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, 31/4: 679-91.

Mello, J.M., 1876. The Bone-Caves of Creswell Crags. – 2nd Paper. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, 32/3: 240-4.

Mello, J.M., 1877. The Bone-Caves of Creswell Crags. – 3rd Paper. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, 33/3: 570-88.

Nash, G.H., 2008. Northern European hunter/fisher/gatherer and Spanish Levantine rock art: A study in performance, cosmology and belief. Trondheim: NTNU.

Nash, G.H., 2025. Identifying potential Upper Palaeolithic paintings in Church Hole, Creswell Crags, Nottinghamshire, England. Adoranten 59-73.

Nash. G.H., Beardsley, A. & Harrod, S., 2025. A Recent Geospatial Survey of Church Hole Cave, Creswell Crags, Nottinghamshire. Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society, 30 (1), forthcoming.

Pettitt, P., Gamble, C., and Last, J., (eds.) 2008. Research and Conservation Framework for the British Palaeolithic. London: English Heritage & The Prehistoric Society.

Pettitt, P., Chamberlain, A., and Wall, I., 2012. A research framework for the archaeology, palaeontology and ecology of Creswell Crags and the Limestone Heritage Area. Unpublished Report.

Pettitt, P. and White, M., 2012. The British Palaeolithic: Hominin societies at the edge of the Pleistocene world. Routledge.

Pike, A.W.G., Gilmore, M., Pettitt, P., Jacobi, R., Ripoll, S, and Muñoz, F., 2005. Verification of the age of the Palaeolithic cave art at Creswell Crags, UK. Journal of Archaeological Science 32, 1649-55.

Pike, A.W.G., Gilmore, M. and Pettitt, P., 2009. Verification of the age of the Palaeolithic cave art at Creswell Crags using uranium-series disequilibrium dating. In P. Bahn & Pettitt, P. (eds.) Britain’s Oldest Art: The Ice Age cave art of Creswell Crags. English Heritage, 87-95. http//:doi:10.1016/j.jas.2005.05.002

Ripoll, S. and Muñoz, F.J., 2007. The Palaeolithic Rock Art of Creswell Crags: Prelude to a Systematic Study. In P. Pettitt, P. Bahn & S. Ripoll (eds.) Palaeolithic Cave Art at Creswell Crags in European Context. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 14-33.

Wall, I. and Jacobi, R.E.M., 2000. An assessment of the Pleistocene collections from the cave and rockshelter sites in the Creswell Area. Unpublished Report.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ British Isles Prehistory Archive

→ British Isles Introduction

→ Stonehenge

→ Avebury

→ Kilmartin Valley

→ The Rock Art of Northumberland

→ Rock Art on the Gower Peninsula

→ New rock art discoveries in the Peak District National Park

→ Painting the Past

→ Church Hole - Creswell Crags

→ Signalling and Performance

→ Cups and Cairns

→ Ynys Môn, North Wales

→ Bryn Celli Ddu

→ Remembering Stan Beckensall

→ The Prehistory of the Mendip Hills

→ The Red Lady of Paviland

→ Megaliths of the British Isles

→ Stone Age Mammoth Abattoir

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network

![Panel C. The engraved cervid and/or wild fowl figures and the surrounding rock surface [centre of image] (30cm scale used)](images/figure15a.jpg)

![Panel C. Raw images showing a curvilinear haematite spread, probably the result of the application of an applied haematite. Note, the change in colour hue [from deep red (L) to crimson (R)], suggests the formation of a calcite flow over the two engravings.](images/figure17a.jpg)

![Panel C. D-Stretch images showing a curvilinear haematite spread, probably the result of the application of an applied haematite. Note, the change in colour hue [from deep red (L) to crimson (R)], suggests the formation of a calcite flow over the two engravings.](images/figure18a.jpg)