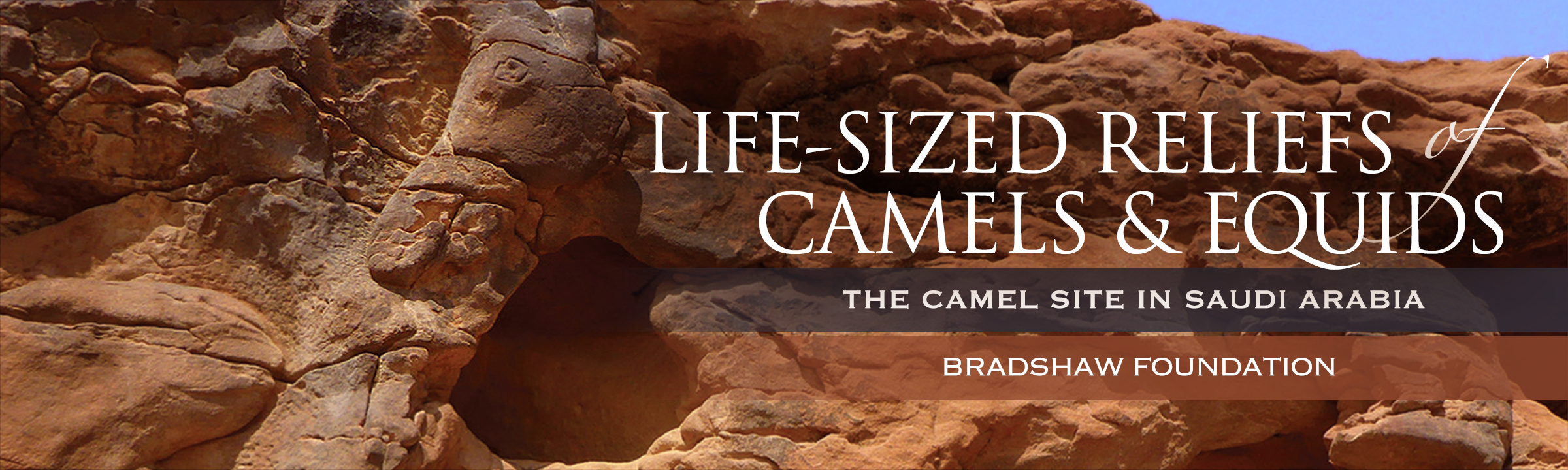

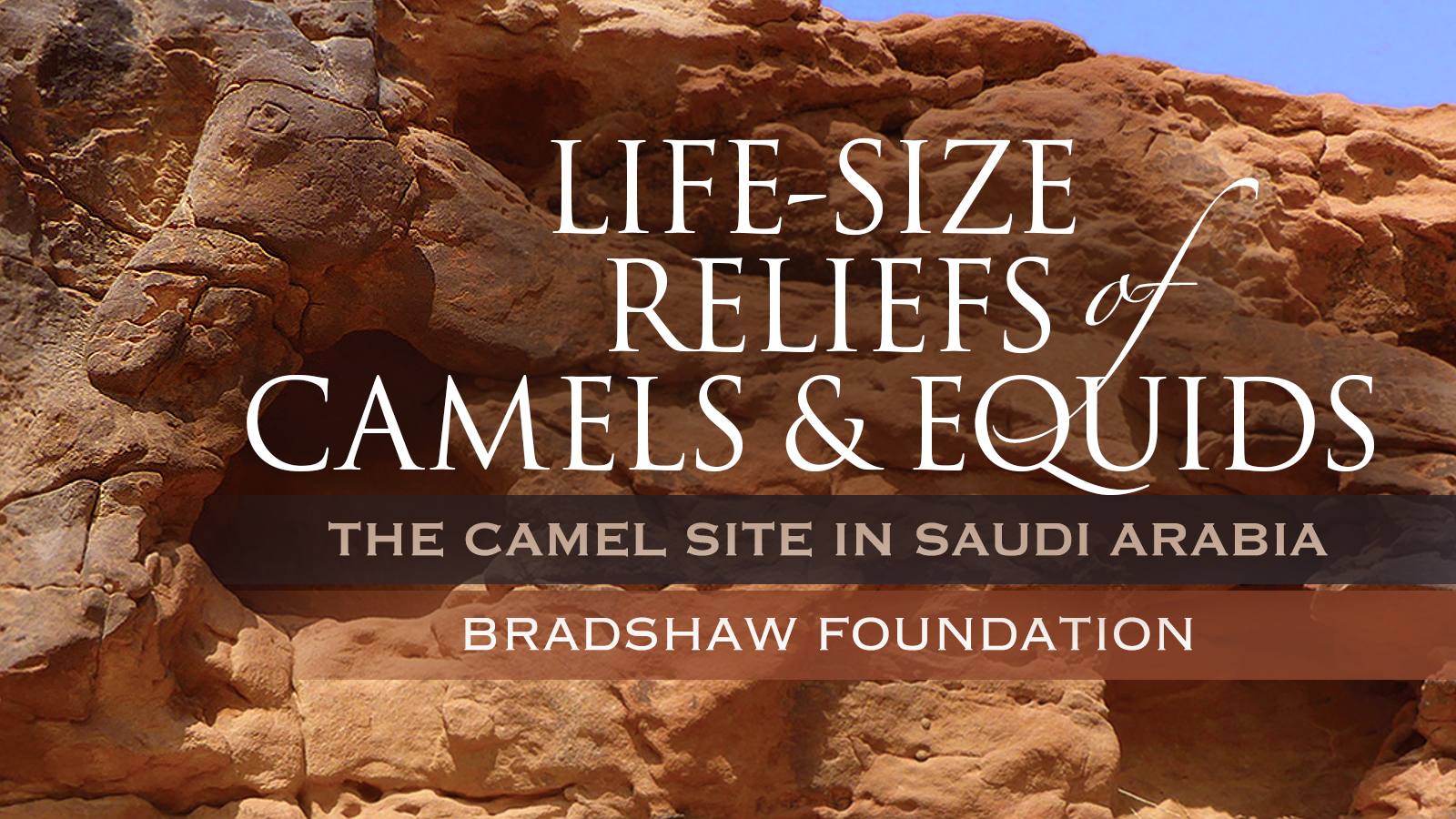

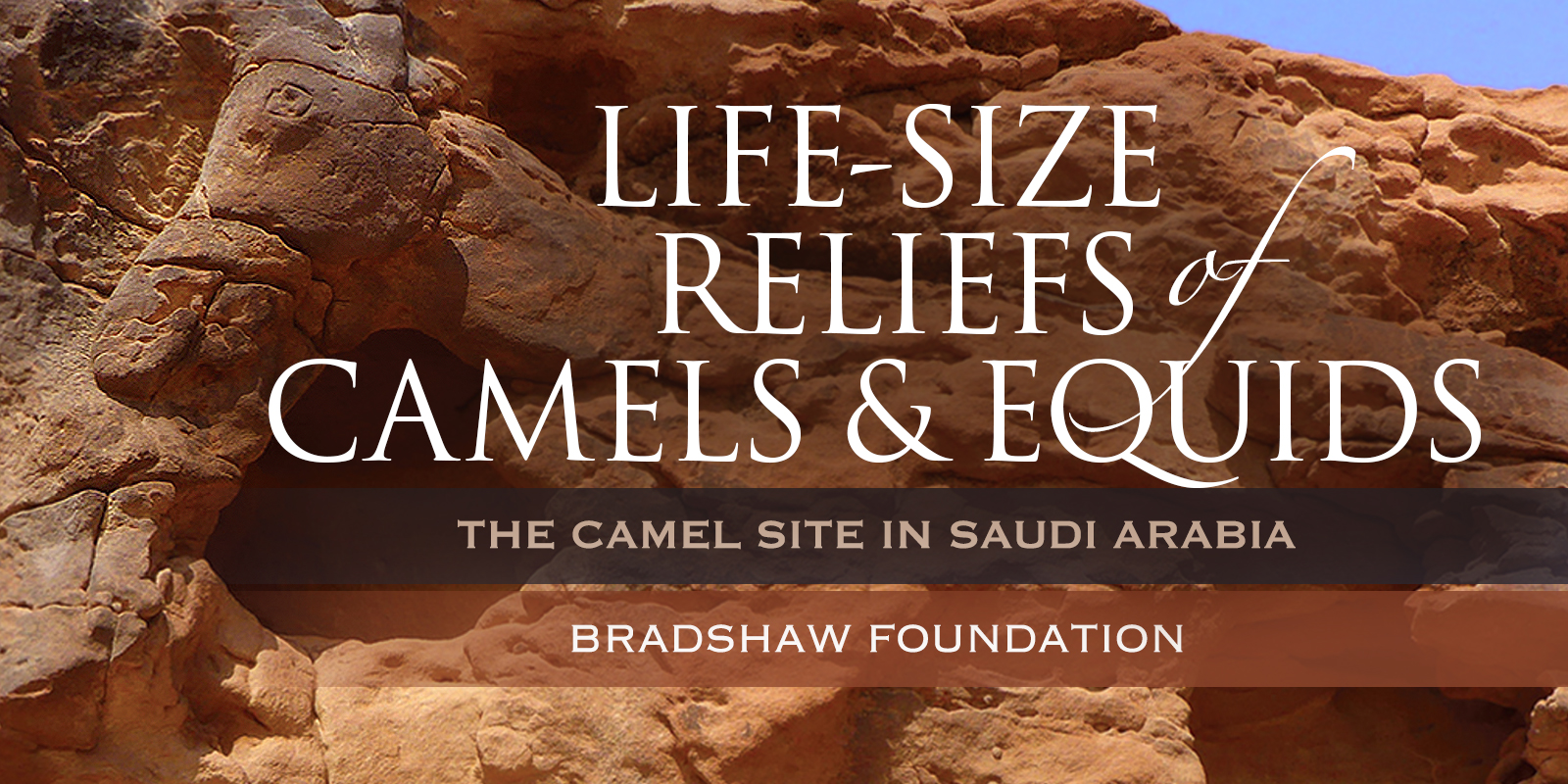

The Camel Site in Saudi Arabia

Guillaume Charloux (CNRS, UMR 8167 Orient & Méditerranée)

Abdullah M. AlSharekh (King Saud University)

The Camel Site (near Sakaka in al-Jawf Province, Saudi Arabia) is a unique rock‐art site in the Near East and its life-sized animal reliefs are amongst the oldest in the world. It was first recorded in 2016, after it was reported by Hussain Al‐Khalifah, the former local representative of the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage (SCTH) in the Jawf region (Charloux et al., 2018). Since 2018, the site is being studied by an international Saudi‐French-German team co-directed by Dr G. Charloux, Dr M. Guagnin and Dr A. AlSharekh, assisted by A. al-Qaeed and Y. al-Ali, representatives of the Ministry of Culture, as part of an agreement between the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage (today Heritage Commission of the Saudi Ministry of Culture) and the French National Center for Scientific Research (with financial support from CNRS, the UMR 8167, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Dahlem Research School at Freie Universität Berlin, the French Labex Resmed from Sorbonne University (ANR-10-LABX-72, ANR-11-IDEX-0004-02), the Cefrepa and by a grant from the Gerda Henkel Foundation (AZ 43/Z/18)).

The Camel Site (near Sakaka in al-Jawf Province, Saudi Arabia) is a unique rock‐art site in the Near East and its life-sized animal reliefs are amongst the oldest in the world. It was first recorded in 2016, after it was reported by Hussain Al‐Khalifah, the former local representative of the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage (SCTH) in the Jawf region (Charloux et al., 2018). Since 2018, the site is being studied by an international Saudi‐French-German team co-directed by Dr G. Charloux, Dr M. Guagnin and Dr A. AlSharekh, assisted by A. al-Qaeed and Y. al-Ali, representatives of the Ministry of Culture, as part of an agreement between the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage (today Heritage Commission of the Saudi Ministry of Culture) and the French National Center for Scientific Research (with financial support from CNRS, the UMR 8167, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Dahlem Research School at Freie Universität Berlin, the French Labex Resmed from Sorbonne University (ANR-10-LABX-72, ANR-11-IDEX-0004-02), the Cefrepa and by a grant from the Gerda Henkel Foundation (AZ 43/Z/18)).

The aim of the project is to improve our understanding of the archaeological context, age and the overall significance of the Camel Site, as well as the establishment of a detailed heritage management plan for the site. To achieve this the project works in collaboration with international researchers and utilizes cutting edge technology including Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating, hi-resolution 3D documentation and modelling, portable X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry (pXRF), Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS) and traceological (use-wear) analysis of stone tools.

In addition to 9 panels containing a total of 15 large reliefs that had been identified during first, brief visits to the site, detailed surveys have documented 3 additional panels with 6 animal reliefs. This was possible by carrying out detailed and repeated analyses of rock surfaces at at different times of day, to take advantage of changes in light condition that help to reveal even faint traces of eroded and heavily damaged reliefs.

Among the main new discoveries, was the identification of a previously unknown panel containing at least two life-sized camels carved in high-relief that are in extremely poor condition. Of one camel only the legs, neck and parts of the body and head remain, and of the second only the front legs and parts of the body are visible today. We also identified a carving of a simpler, life-sized carving of a camel on a fallen rock slab. In addition, new surveys also revealed three sets of small-scale reliefs, including a row of small equids carved in bas-relief and small camel engravings.

Results now show a very dense concentration of reliefs at the Camel Site (21 individual life-sized bas- and high reliefs), with the majority visible from one of two main viewpoints. We estimate that originally the site would have been most impressive when approached from the modern track that passes the western edge of the rock spurs. Unlike two-dimensional rock art, which is thought to have been highly visible when freshly engraved on patinated rock surfaces, the creation of reliefs would have necessitated the removal of much of the rock surface around the actual carving. Visibility of the reliefs thus relied on the position of the sun, the position of the viewer, and the resulting combination of light and shadow. We believe this is also the reason the site has not received more attention in the recent past, as this effect has increasingly been lost with the deterioration of the panels.

reliefs –here a row of 3 equids, although

only the body of the first has been preserved

with legs of 2 large camels as well as

two small camels in low reliefs (centre left)

In order to achieve a detailed record of the reliefs in their current state of preservation, before further fragments or entire panels are lost to natural or anthropogenic destruction, all panels at the Camel Site were systematically recorded. We have created high-resolution 3D models of all panels, which plug into a larger model of the whole archaeological site. These models use dense point clouds generated from multiple high-resolution photographs taken from various different angles. This was carried out by a specialized 3D engineer, P. Mora (CNRS). 3D recording was particularly important for the newly discovered panels, as their poor state of preservation leaves them at risk of complete disintegration in the near future. Our 3D models also help us to identify their original shape by viewing them from different angles in a virtual environment and will form the basis for virtual reconstructions.

A team specialized on rock varnish analysis, led by M. Andreae (MPI Chemistry), working with the SGS (Saudi Geological Survey), visited the Camel site in October 2018. Their participation in the project had the aim of providing new insights into the dating of the camel and equid reliefs, using non-destructive, portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) to measure intact varnish on reliefs and engraved petroglyphs, based on a new methodology that has already established age estimates for engravings other major rock art sites in Saudi Arabia, including Shuwaymis, Jubbah and the Hima region (Macholdt et al., 2018; Macholdt et al., 2019; Andreae et al., 2020).

Areas coated with dark rock varnish and showing low levels of erosion were targeted for measurements, as this allows a good comparison between the engraving and the natural surface of the rock. Results were then compared with measurements from datable and less varnished engravings in the area, such as inscriptions. Results suggest maximum ages between 7000 and 8000 years and are close to the maximum areal density of rock varnish.

A detailed study of the fallen rock relief fragments revealed that fragments 5,6 and 7 behind spur A were probably amongst the earliest fragments to have fallen and are also the only fragments that still lie in their original fallen position (all other fragments have been moved by bulldozing in the recent past, preventing a scientific assessment of their age). We collected sediment samples from underneath the fragment for Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating. This method measures when sediments were last exposed to sunlight. Of our two samples, one had been affected by water run-off. However, the other sample gave a minimum age of 3000 years, suggesting that by 1000 BC erosion of the site was sufficiently advanced for panels to fall. This process still continues, with one panel likely to fall within the next decade.

To allow more precise dating of occupation deposits that remain at the site, a small test trench (1 m x 5 m) was excavated by R. Crassard and Y. Hilbert underneath a small overhang. Radiocarbon dates of faunal remains provided ages of around 5600 and 5200 BC which matches the estimated age of the lithic assemblage, which includes a number of arrowheads that show parallels with projectiles known from Neolithic sites in southern Levant and from Jordan.

If collagen is preserved in the bone fragments, its protein structure can help us identify the animal species, even if the bone fragments are too small for standard archaeozoological identification. Animal bones from the site are very fragmentary and unfortunately the collagen was too degraded for ZooMS analysis. Further analysis of the faunal assemblage is still underway.

During the survey we found some stone tools that could have been used to carve the reliefs. To test this we carried out experiments with stone tools. Raw material was collected, and a range of different stone tools were produced in the courtyard of our accommodation to prevent contamination at the site. The resulting tools were then used in a variety of techniques and sandstone fragments were hammered, chiseled and scraped for prescribed periods of time. The (modern) tools were then catalogued for microscopic analysis. This will give us a comparative dataset that records the types of damage resulting from the use of stone tools to carve sandstone. The comparison will also help us to understand how the tools found at the Camel Site were used, and how often they had to be replaced. It is our current understanding that the carvers were aided by individuals who continuously sharpened tools and then handed them back to the engravers. In fact, multiple similar tools were likely in use at the same time. The amount of work involved in the procurement of raw material, building of scaffolding or rigging, carving of the reliefs, making and sharpening of the required tools, and the provision of food and drink for all involved in the work gives some insight into the logistic and communal effort that was required to create the reliefs at the Camel Site.

As part of this project, we also conducted a study of large (two-dimensional) depictions of camels in western Arabia, collecting data from publications in books and journals, as well as recent discoveries by tourists (Charloux et al., 2020). We were able to identify five traditions of representations. Among these, a previously unknown tradition of life-sized naturalistic camel engravings was identified around the Nafud desert. These new comparative studies now suggest that the reliefs of the Camel Site may be a three-dimensional version of a wider reaching Neolithic rock art tradition (Charloux and Guagnin, under review). In fact, the only feature that distinguishes large camel engravings from Camel Site reliefs is the extent to which the image is raised from the background. Large camel engravings in the Sakaka and the Jubbah/Jebel Misma areas not only mirror the reliefs of the Camel Site in their naturalism and detail but also show similarities in engraving technique as some are partially depicted in low-relief. Large camel engravings also overlap spatially with the Camel Site and share a symbolic tradition where engravings and reliefs predominantly show male camels with bulging necklines, a feature that is typical of male camels in rut (Gauthier-Pilters and Dagg, 1981). Although wild camels are extinct and their behaviour is not known, camels that are allowed to roam freely are usually in rut between December and March, during the second half of the wet season when grazing conditions are optimal. This may be reflected in camel reliefs and camel engravings, which usually show well-fed animals with good fat storage in the hump and strong muscular bodies.

A detailed heritage management assessment of the site indicates that the reliefs are in danger of imminent destruction from erosion, and the site has also suffered extensively from vandalism, bulldozing and agricultural irrigation.

The carved panels are mainly affected by wind erosion and salt weathering caused by temperature and humidity differences. The sandstone surfaces were initially protected by the formation of rock varnish, which hardened and protected surfaces for millennia, a phenomenon called case hardening (Dorn et al., 2017). Once the outer, harder layer of rock was removed by wind erosion, the internal, softer sandstone quickly erodes, leaving only an outer shell that is prone to collapse. This causes the carved blocks to fall down the slope and either break up over time or collapse under their own weight. Where fallen boulders have contact with the ground rising moisture and salt also accelerates the decomposition of the sandstone.

The area surrounding the rock spurs where the panels are located is also an important part of the archaeological site, and numerous chipped stone scatters are still visible on the surface. Unfortunately, this area has been heavily damaged by agricultural landscaping through bulldozing. Google Earth imagery analysis shows that most of the bulldozing occurred before 2003, with some further bulldozing activity between 2003 and 2009. Since then, the fields appear largely abandoned, and as such the situation appears to be stable.

It is now important to protect the site in order to prevent any future bulldozing and agricultural or other activities in the area, and agricultural refuse and equipment need to be removed. The area around the site has also been affected by flooding, which requires management. Despite the advanced state of erosion, once protected and restored, the Camel Site will have considerable potential for tourism and education.

The directors of the Camel Site Archaeological Project wish to thank HRH Prince Badr b. Abdullah b. Mohammed b. Farhan Al-Saud, Minister of Culture, and to HRH Prince Sultan Bin Salman Bin Abdulaziz al-Saud, the former President of the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage for giving us permission to study the extraordinary Camel Site in northern Saudi Arabia. In the field we also received the support of General Director for Archaeological Excavations Dr Abdullah al-Zahrani and his assistants. We thank them all sincerely. We would also like to thank the regional service of the SCTH in Jawf province, particularly Mr. Yasser al-Ali and Mr. Ahmed al-Qaeed.

ANDREAE, M. O., AL-AMRI, A. M., ANDREAE, C. M., GUAGNIN, M., HAUG, G., JOCHUM, K. P., STOLL, B. & WEIS, U. 2020. Archaeometric studies on pretroglyphs and rock varnish at Kilwa and Sakaka, northern Saudi Arabia. Arabian archaeology and epigraphy, 31, 219-244.

CHARLOUX, G., AL-KHALIFAH, H., AL-MALKI, T., MENSAN, R. & SCHWERDTNER, R. 2018. The art of rock relief in ancient Arabia: new evidence from the Jawf Province. Antiquity, 92, 165-182.

CHARLOUX, G., GUAGNIN, M. & NORRIS, J. 2020. Large-sized camel depictions in western Arabia: A characterisation across time and space. Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, 50, 85-108.

CHARLOUX, G. & GUAGNIN, M. under review. Large Naturalistic Engravings of Camels: An Unknown Rock Art Tradition in Northern Arabia. In: LUCIANI, M. (ed.) The Archaeology of the Arabian Peninsula 3: Mobility in Arabia. Proceedings of the International Workshop held at the International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East in 2018. Vienna: OREA.

DORN, R. I., MAHANEY, W. C. & KRINSLEY, D. H. 2017. Case Hardening: Turning Weathering Rinds into Protective Shells. Elements, 13, 165-169.

GAUTHIER-PILTERS, H. & DAGG, A. I. 1981. The Camel. Its Evolution, Ecology, Behaviour, and Relationship to Man, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press.

GUAGNIN, M., CHARLOUX, G., ALSHAREKH, A. M., CRASSARD, R., HILBERT, Y. H., ANDREAE, M. O., PREUSSER, F., DUBOIS, F., BURGOS, F., FLOHR, P., STEWART, M., MORA, P., ALQAEED, A. & ALALI, Y. 2021. Life-sized Neolithic camel sculptures in Arabia: A scientific assessment of the craftsmanship and age of the Camel Site reliefs. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 103165.

MACHOLDT, D. S., AL-AMRI, A. M., TUFFAHA, H. T., JOCHUM, K. P. & ANDREAE, M. O. 2018. Growth of desert varnish on petroglyphs from Jubbah and Shuwaymis, Ha’il region, Saudi Arabia. The Holocene.

MACHOLDT, D. S., JOCHUM, K. P., AL-AMRI, A. M. & ANDREAE, M. O. 2019. Rock varnish on petroglyphs from the Hima region, southwestern Saudi Arabia: Chemical composition, growth rates, and tentative ages. The Holocene, 29, 1377-1395.