Within the field of archaeology, the term Archaic is applied in Western North America primarily to a span of human history that follows the Paleoindian period and comprises the five millenia from approximately 6000 to 1000 B.C. As a rule, the Archaic lifeway, distinguished by nomadic bands searching for seasonally available goods (Cole 1990:10), lasted much longer than the accepted time frame for the Archioiconic period of rock art. The term Archaic chronologically alludes to any rock art older than 1000 B.C.

There is solid archaeological evidence that the earliest occupants of the American Southwest were specialized big-game hunters, generally referred to as Paleoindians, and roaming Arizona prior to 7000 B.C.

Why Paleoindians did not depict these big-game animals, when there is clear evidence that they hunted and ate them, will probably always remain a mystery. All earliest Arizona rock art consists almost entirely of nonfigurative motifs. It is possible that, unlike the Palaeolithic groups in Europe and Asia, Paleoindians had strict taboos against the creation of realistic game animals or humanoid figures, which accounts for their production of primarily abstract-geometric designs.

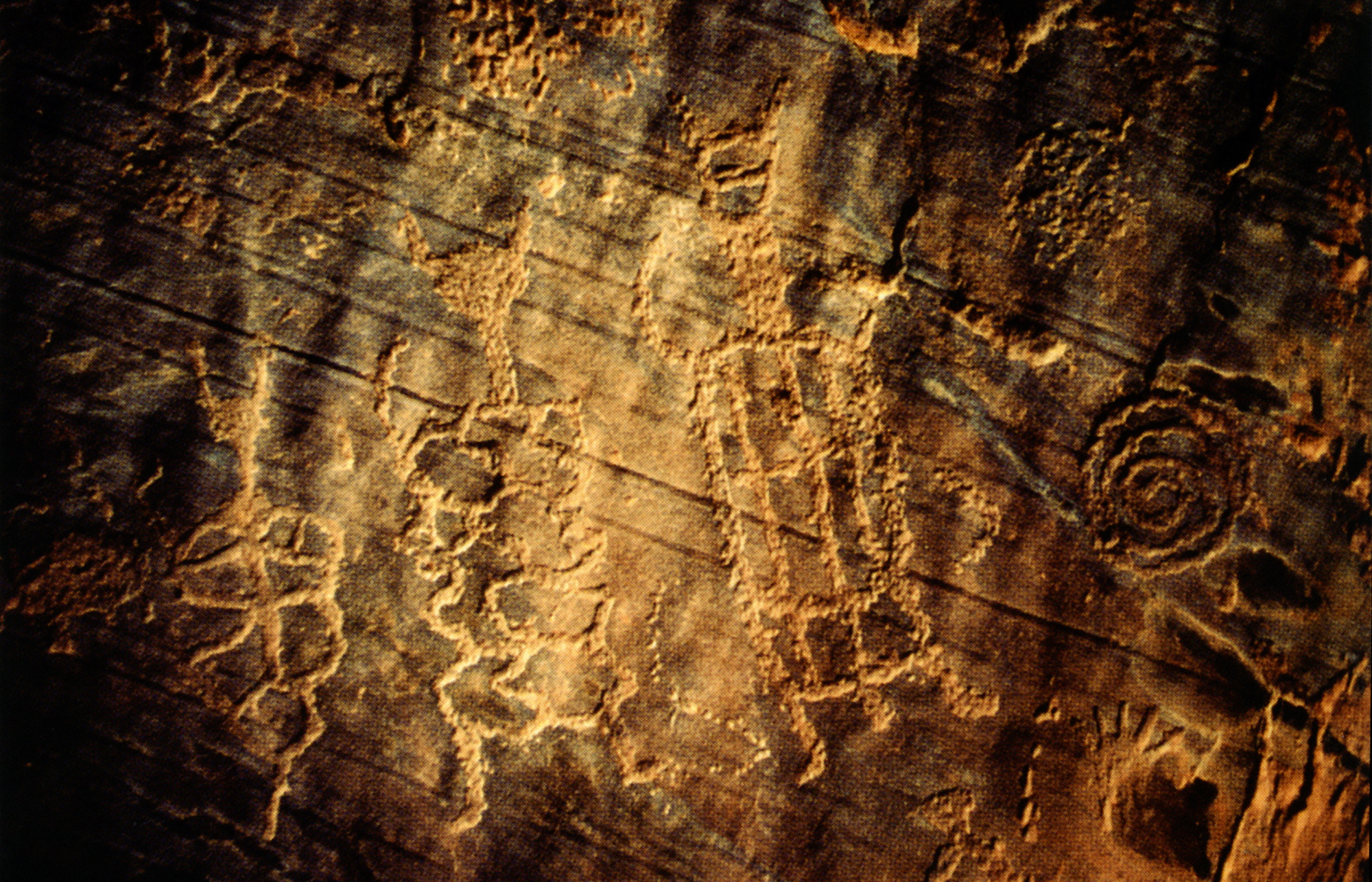

The most ancient of Arizona's rock art is thought to have been made between roughly 6000 and 1000 B.C., an era characterized by a new adaptive lifeway pattern involving the gathering of wild foods, supplemented by the hunting of smaller animals. The majority of this most ancient art consists chiefly of abstract-geometric markings, although there are figurative elements such as atlatls, foot- and handprints, bird tracks, and possible vulvalike designs. Occasionally there are anthropomorphs and quadrupeds. This is the Western Archaic Geocentric Tradition. Sites are widely dispersed across Arizona, and are divided into two subsets; petroglyphs and pictoraphs. Both show an overriding preference for imagery derived from phosphenes, autogenous and involuntary abstract-geometric form constants that are hardwired into the mammalian visual system and are produced by the human brain without external stimuli. It has been theorized that, the world over, nonfigurative or noniconic motifs in paleoart preceded representational images, and all motifs created prior to iconic ones are based on phosphenic elements (Bednarik 1994a).

The markings are distinguished by deeply carved lines on boulders, flat-lying slabs and low cliffs. They are heavily revarnished and seriously eroded. Motifs include a myriad of abstract figures, both of curvilinear and rectilinear kind: circles, spirals, lines, arcs, grids, meanders, squigglemazes, rakes, ladders, zigzags, lattices, sets of parallel lines and the like. Major sites fitting this tradition are found in the Tank Mountains, the Growler Mountains, the Picacho Mountains and the Hedgepeth Hills. Examples of the early Geocentric Painted Tradition are less common in Arizona. Those that exist are rendered in red, black, white, orange or yellow.

Rather than hunting magic, researchers are now considering phospenes - entoptic phenomena, primitives, or visual archetypes - as an explanation. Phospenes are experienced by all humans, including blind people, and can result from a wide range of causes such as hyperventilation, fatigue and hunger, migraine headaches, meditation and intense concentration, ingestion of hallucinatory drugs, and even pressure put on the closed eye. Believed to constitute fundamental universal elements of early art, they cannot be influenced by cultural conditioning. Due to its homogeneous global ubiquity, the elemental repertoire of the visual arts, consisting of arcs, dots, grids, circles, triangles, sets of parallel lines, radials, spirals, meanders and squiggles, in an infinite variety of arrangements and constructions, seems to indicate "a kind of universal, innate visual grammar" (Engel in Fein 1993: back cover).

In the late 1980's David Lewis-Williams and Thomas Dowson proposed an interpretive approach derived from shamanism and neuropsychology; the world over, hunter-gatherers, whether of prehistoric antiquity or still extant, practice a shamanistically oriented brand of religion. At the core of the shamanistic ideology stands a ritual specialist who, on behalf of his or her band, acts as an intermediary between the world of mortals and the supernatural realm, healing the sick, influencing the weather, controlling game, assuring human, animal and vegetal fertility, and restoring lost harmony by harvesting supernatural power from the spirit world. All of this through dreams, trances and hallucinations - altered states of consciousness. The neuropsychological model, which claims universality based on its biological roots and neuroscientific research of the brain, has shown that in trancelike states the human mind generates a broad range of hallucinations. The most significant of these, in terms of rupestrian production, are visual.

Were abstract geometrics a protolanguage? Colloquially, rock art images are frequently characterized as "rock writings", but likening them to a primitive script is unwaranted. Assemblages of petroglyphs or pictographs are too random and diverse to meet the stringent consistencies required of a writing system. However, the notion of rock art as visual communication is acceptable, especially when directed at a supernatural world. One explanation for these nonfigurative glyphs could have been their creators' belief that the controlling entities of some perceived other-world were thought to relate to abstract essences and concepts more readily than to realistically portrayed objects. However, it is difficult to conceive that this motivation could have been adhered to cross-culturally in a uniform way.

Were the abstract images for only a chosen few? Since it is assumed that the subject iconography was directly linked to essential rituals promoting preservation of the existing social organisation and the underlying power structure, researchers have speculated that it may have been advantageous for those in positions of leadership and authority to limit access to the function and meaning of the art by resorting to abstract geometrics. The purpose and symbolism may have been disguised, and only a few privileged initiates would have been privy to their actual significance. However, this is impossible to prove; the abstract signs may simply have functioned to enculturate - humanize, socialize or sacralize the existing landscape.

Perhaps a more plausible answer to the "abstract enigma" may be gleaned from Ellen Dissanayake's discussions of art. Arguing (1992a:11) from an ethological standpoint that art is not merely a peripheral epiphenomenon but a biologically endowed behavioural proclivity of every human being, she defines the core of art as "making special" and builds a strong case for it as having been necessary to human evolution, and as being, until now, an undescribed universal characteristic of humankind (1999:27). In subsequent writings she also uses the term "artification" to emphasize her contention that the arts are something that people do, thereby emphasizing the process of making or doing rather than the resulting product. Rock art was a way of "making special". Geometric configurations were imposed by humans on the natural world to provide a cultural "super"-order and a way of mainfesting a command of space, and signifying safety, security and understanding. Randall White (2003:13-15) concurs; "Can humans experience social solidarity in the absence of shared representations...? Can religion even exist without icons and visual images?"

A final question relating to Archaic rock art that researchers are now asking is how often the carvings were made and how often they were seen. How did this rock art function in a ceremonial context, given that it is scantily distributed and usually separated by large spatial intervals? Research by Henry Wallace (2006) in Arizona suggests, by analysing the numbers, that many hundreds of generations of early hunter-gatherers did not create designs and petroglyph production was not a ritual tradition. However, whilst this does not denegrate the act of making the art, researchers now acknowledge that greater heed must be paid to human interaction at established rupestrian sites. Once a particular place in the landscape had been consecrated by "extra-ordinary" markings, it may have proved useful for many generations. This in itself makes rock art a multi-functional phenomenon, and a single hypothetical postulate can not explain it all. Rock art, at any given time, had not only many functions and motivations but many meanings as well.

Originally designated the Colorado River Style, the predominantly geocentric Grapevine Style is found in California and Nevada as well as Arizona. Based mainly on data collected by Don Christensen et al. the style is 95% nonrepresentational with designs predominantly symmetrical and geometric.

Hallmarks of the style, which is dominated by petroglyphs, include rectilinear, oval, or oblong geomorphs reminiscent of ancient Egyptian cartouches. These bounded forms contain simple to elaborate internal patterns. Other abstract elements include wavy, zigzag or straight lines and such figures as outlined crosses, rakes, ladders and spirals, as well as an array of circle motifs such as rayed and concentric circles. Also found are items shaped like capital letters I and T as well as double crenelation "pipette" designs, hourglass figures and masklike motifs. The representational motif index of this style contains a few human stick figures, with exaggerated hands, fingers, feet or toes. Stick-figure zoomorphs are predominantly ungulates, especially bighorn sheep. Also found are long-tailed or phallic anthropomorphs, as well as hand- and footprints. The Grapevine panels display both randomly placed and juxtaposed depictions.

Based on diagnostic artifacts - Gypsum and Elk dart points - found at sites, the style had its beginnings in the terminal stage of the Archeoiconic period (ca. 2000 B.C.) and continued into the ceramic periods (post-A.D. 700) until at least late prehistoric times (ca. A.D. 1500).

This period saw the clear shift from noniconic elements to representational images, demonstrated by 3 styles; Glen Canyon Linear, Grand Canyon Polychrome and Palavayu Anthropomorphic. This break with the established and long-lived noniconic imagery was the result of a far-reaching innovation in the lifeway and worldview of the cultural groups responsible for creating the art. It reflected the growing emergence of an anthropocentric thought world and cosmology anchored in a heightened emphasis on shamanism. Climatic conditions changed dramatically around this time, and the environmental shift affected the populations of large game animals which brought about a dwindling of food resources. During times of stress Archaic people may have turned to religion and shamanistic activities to magically increase the number of animals and plants. Thus the art should not be seen as wall ornaments but as the product of shamanistically oriented ideologues who encultured their environment according to their forager world-understanding. If this is the case, the body of art of the three styles is a testamonial to one of the oldest religious ideologies in Arizona.

The style is essentially biocentric - life-form oriented with human and animal elements. Static anthropomorphic figures are a hallmark of the style, with rectangular and ovoid torsos in outline form, decorated with crossbars, hachures, grids and other interior markings. The figures range from 20 to 30 cms to nearly life size, and often endowed with disproportionate tiny heads, sporting horns and fanciful projections. Facial features are rare except for dot eyes. Quadrupeds, such as bighorn sheep, deer, or elk, have oval and rectangular bodies with tiny heads and stick legs similar to the humanlike figures. Additional iconic depictions include snakes, insects and spiders. There are also nonfigurative motifs, reflecting the Western Archaic Geocentric Tradition. The dating of this style is thought to be from as early as 6000 B.C. to as late as A.D. 500.

This is the only painted biocentric art complex in Arizona hailing from the Archeoiconic period. Sites as a whole typically exhibit more than one colour (usually red and white, and sometimes black, orange, green and yellow) although much of the style's individual elements are monochromatic (usually white). The style is easily recognized by a mixture of stylized, immobile anthropomorphs, comparatively realistic zoomorphs, and linear geometric designs. Its signature elements are over-elongated, finely decorated anthropoid figures, such as those in the "Shamans' Gallery" of the Grand Canyon, the style's type-site. The anthropomorphic groups are usually arranged in rows, depicted in upright frontal view, with elongated torsos embellished by internal markings - parallel lines, wavy lines, dots and squares. The sites are usually in inaccessible overhangs. The art has not been scientifically dated, but it can be placed in the late Archeoiconic period (3000 - 1000 B.C.) on the basis of stylistic similarities to the Barrier Canyon Style in Utah and the Pecos River Rock Art Tradition in Texas. The panels are often crowded, with superimpositioning. The imagery bears the hallmarks of shamanistic visions; figures appear to be transforming, and some appear to be emerging from holes and cracks. For these reasons it is thought the art was connected to ceremonial rituals, and perhaps associated with agave harvests.

The word 'Palavayu' refers to the traditional Hopi term for the Little Colorado River - "Red River." The style is anthropomorphic, with some 2,200 images at over 250 sites, although nonanthromorphic elements occur such as zoomorphs, phytomorphs and geomorphs. The style is unique in its area. Research indicates this paleoart was created by hunter-gatherers of the Archeoiconic era. The style is thought to have begun around 4500 B.C. and lasting into the Preformative Period - ca. 1000 B.C. to A.D. 250. It is exclusively petroglyphic, distinguished by idiosyncratic motifs. Most of these are anthropomorphic, primarily in static and front-facing postures. From solidly pecked to patterned-bodied, they display a variety of torso decorations consisting of geometric as well as iconic elements. Many figures are holding objects such as spears, sticks and hoops. Head exteriors include elaborate emanations such as headdresses, antlers, antennae and feathers. Some heads have halos. Most anthroporphs are unsexed although some males are shown in simple phallic fashion.

Zoomorphs include birds, insects and reptiles. There are some therianthropic composites such as humanized rattlesnakes and anthropomorphized owls. Generally, the imagery can be characterized as depicting nonordinary reality dominated by a wide range of specific elements attributable to shamanistic ideology. Much of the style's iconography was likely derived from hallucinations, visions or dreams. According to the neuropsychological model of interpretation, the incorporation of phospenic geometrics into representational designs is a reliable indicator of origin in deep trance. The multitude of interior torso markings may signify the shaman's outward sign of supernatural power. Or, they may reflect esoteric paraphernalia, adornments in the form of body painting and tattooing or ceremonial garments. Other visual features of trance may be the elongation and distortion of the figures, perhaps to suggest levitation or floating. Although no ethnographic information exists as to what techniques the ancient shaman-artists of the Palavayu employed to communicate via trance with the spirit realm, a number of clues in the anthropic depictions suggest the ingestion of psychotropic substances and botanical hallucinogens - datura, Indian tobacco, four o'clock, and the mushroom species psilocybe and fly-agaric. There are fairly realistic portrayals of the datura plant.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ America Rock Art Index

→ The Rock Art of Baja California

→ Baja On Film

→ California Rock Art Foundation

→ Baja In Search of Painted Caves

→ Baja Great Murals Gallery

→ Sierra de San Francisco

→ Baja 2018 Expedition

→ The Rock Art of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands

→ Color Engenders Life

→ The Rock Art of Arizona

→ The Rock Art of Nevada

→ Coso Sheep Cult of East California

→ Coso Range Rock Art Gallery

→ The Rock Art of Moab Utah

→ The Rock Art of the Oregon Territory

→ RAN - USA Colloquium 2018

→ Removal & Camouflage of Graffiti

→ Graffiti Dates & Names

→ Vandalised Petroglyphs in Texas

→ Preserving Our Ancient Art Galleries

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network