February 5th 2024

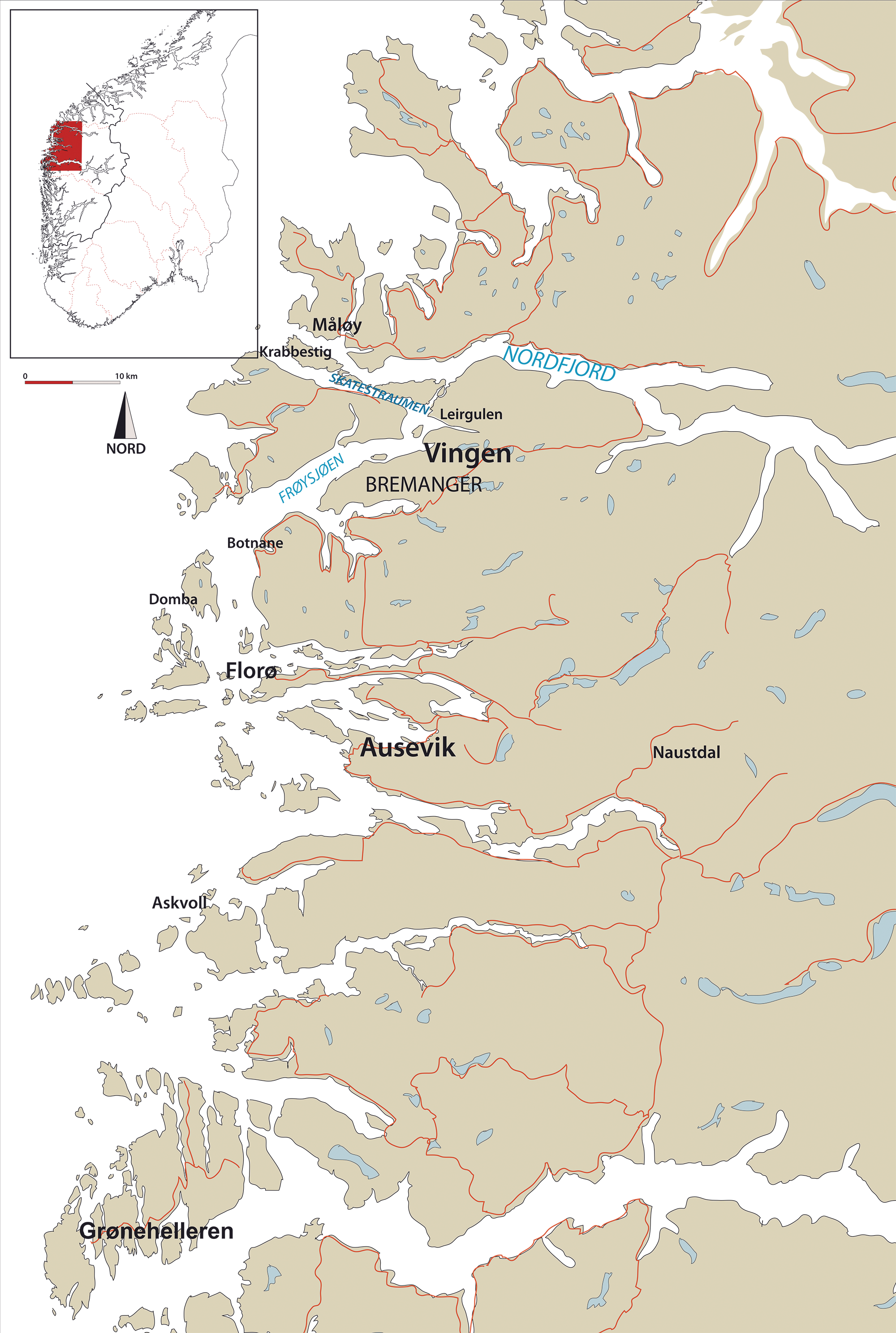

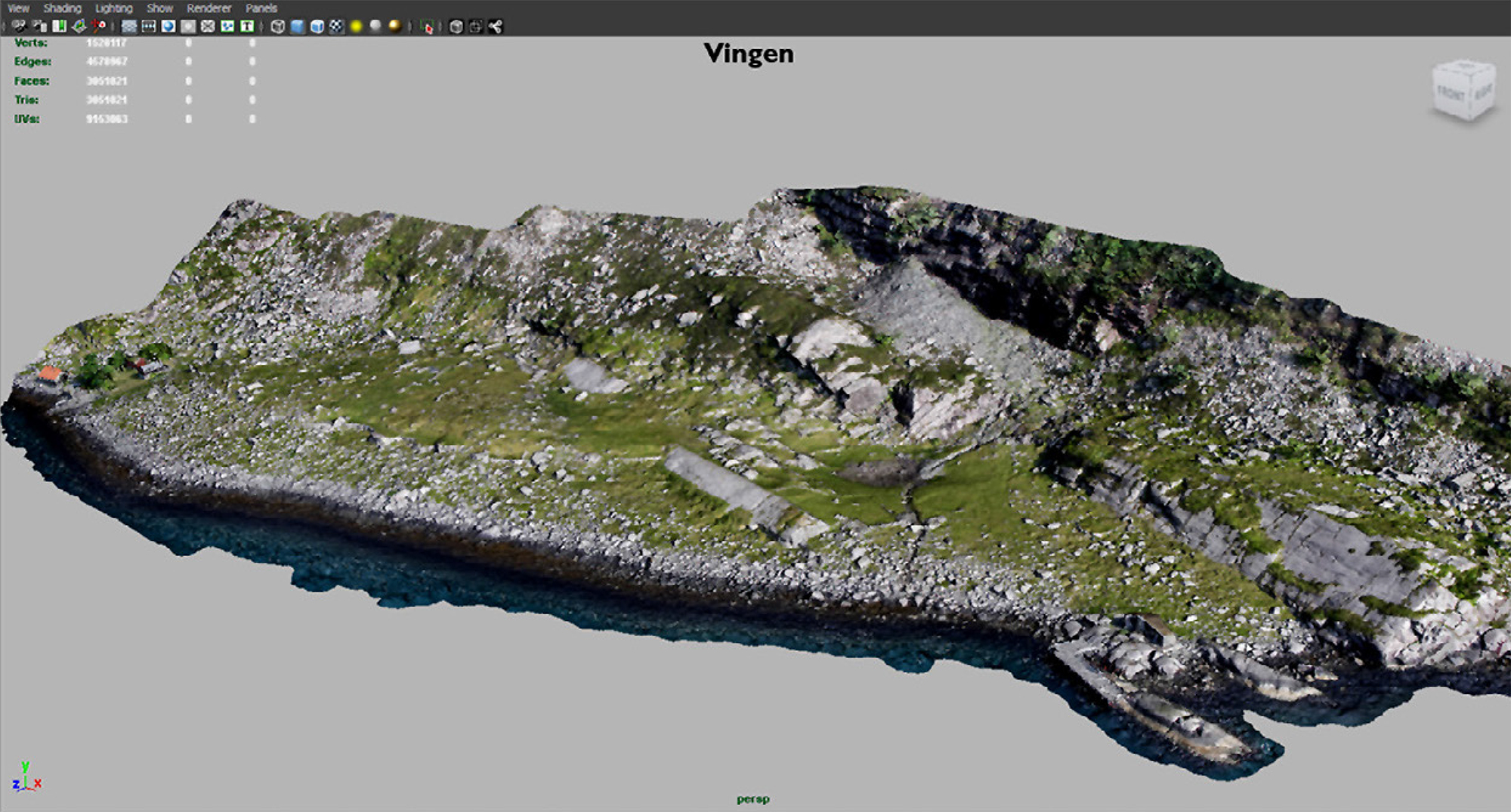

The Ministry of Local Government and Districts approved a new quarry on top of the mountain peak Aksla, despite concern expressed by the National Antiquities Office regarding the damage to the cultural heritage, and protests from both the Norwegian Environmental Protection Association and the Historical Heritage Association. Opposition to this announcement is based on the fact that the establishment of a quarry and the associated industrial activities in this region will have profound negative implications for cultural heritage in Frøysjøen, particularly affecting the rock art site Vingen - one of the most authentic rock art areas in Europe.

National and International Opposition

As well as opposition from various Norwegian institutions, the Ministry of Local Government and Districts decision has been met with despair from respected members and organisations of the International Rock Art community. Trond Andreas Klungseth Lødøen is Associate Professor at the Department of Cultural History at the University of Bergen. He has been involved in the case for over several years, and reacts strongly to the decision: 'It is despairing. To me it is completely absurd. It’s not real.'

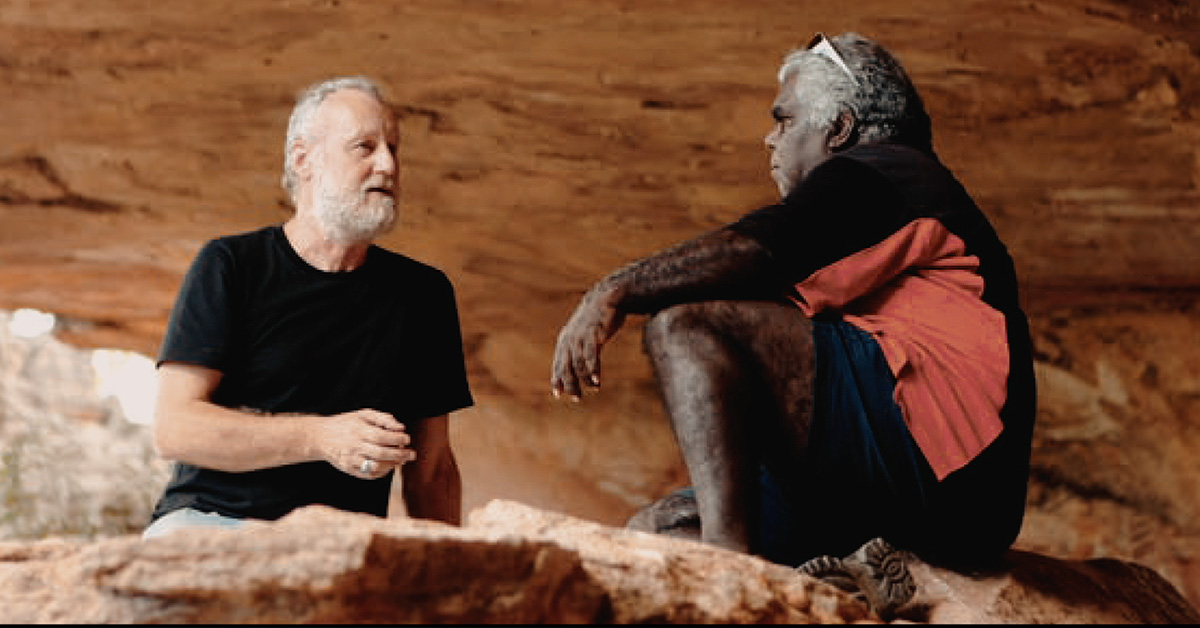

Distinguished Professor Paul S.C. Taçon of Griffith University in Australia and former ARC Australian Laureate Fellow writes: 'I have been studying rock art for 44 years in many parts of the globe and until now had always been impressed with the way Norway cared for and conserved its rock art landscapes, especially Vingen and Alta. Norway has also been known for the sensitive and caring way it conserves natural landscapes so it is deeply disturbing that the Aksla quarry and Inste Bårdvikneset quay developments were approved. If the developments do proceed not only will Vingen and the Vingen landscape never be the same but so too will Norway’s reputation as a country that values its cultural and natural heritage. Indeed, the irreparable impact from the developments for short-term economic gain is both short-sighted and miserly. I am not opposed to such developments outright but am strongly against such developments proceeding in sensitive cultural and natural heritage areas of global importance.'

→ Professor Paul S.C. Taçon - Full Statement

Professor Benjamin Smith, President of ICOMOS the International Scientific Committee on Rock Art, declared: 'I write on behalf of the International Scientific Committee on Rock Art to call upon you to instigate an immediate review of your Ministry’s decision to allow a rock quarry and a shipping quay to be built, in the immediate vicinity of one of the most significant rock art sites in Europe: Vingen.'

→ Professor Benjamin Smith - Full Statement

The lawyer had several other interests, and apart from the rock art, also realised the immediate potential for electricity in the powerful waterfall that cascaded down the slopes at the inner end of Vingen, and persuaded the owner to sell him his property. This was later divided up into sections, and while some are still in the hands of his relatives, the panels with rock art were sold to the Bergens Museum (later the University Museum of Bergen). Ownership of the water changed hands a number of times, and for a while the rock art area was threatened by a hydro-electric power plant that was planned to be built on the site, before the water was fortunately redirected to the neighbouring valleys for industrial use in the 1960s.

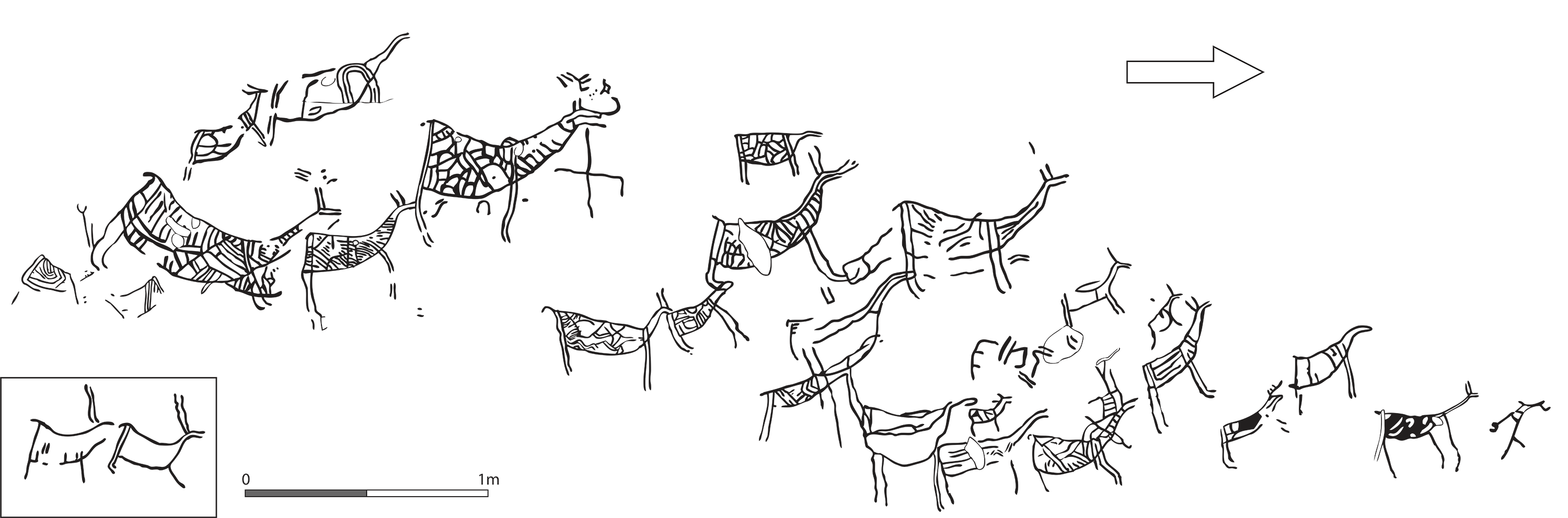

It took Hallström many years to complete his documentation and get it published, which not only included Vingen but also all of the known rock art of the hunter’s style within Norway’s frontiers. In the early 1920s, it seems that Shetelig was tired of waiting for Hallström to publish his work, and was afraid that his evidence would not be completed. At the same time, Norwegian archaeologists had become increasingly aware of the fact that the publication of original material in this country should be reserved for Norwegian researchers. These factors probably resulted in Shetelig giving Johs. Bøe, who was already employed at the museum, the possibility and responsibility of publishing information on all of the rock art in Western Norway. Bøe made his documentation during the summers of 1925 and 1927 and published over 800 images, in his monograph Felszeichnungen im Westlichen Norwegen in 1932.

Apart from information on a number of minor panels published in 1941, Vingen then entered its quietest period since it had been re-discovered at the end of the 1930s. This situation lasted for a couple of decades, before new discoveries were made in the 1960s. Local inhabitants who were using Vingen for grazing and as pasture had come across images concealed beneath turf that had not been documented by the previous archaeologists, leading to extensive excavation work to uncover these areas. The archaeologist in charge of this project was Egil Bakka, who documented a further 700 images with the valuable help of locals such as Peder Vingen and his niece Helga Vingelven. Bakka and his helpers almost doubled the amount of rock art that was known by Hallström and Bøe, although he was unable to publish his work as he fell ill and subsequently died. He did manage to contribute a number of brief articles in several journals, which have served as major contributions to the history of Scandinavian rock art research. He left behind a large amount of documentation, including pictures, tracings and casts, as well as a number of well-written diaries.

Throughout the 1970s the public became increasingly interested in the site, and at the same time the tourism industry asked for better accessibility. This resulted in the appearance of walkways between the largest panels, information brochures and signposts. One of the more unfortunate consequences of this public interest was the painting of the carvings to increase their visibility. At the same time, it became clear that the rock art was suffering from the effects of weathering, and a new type of documentation was included on the agenda–surveying damage. Hallström and Bøe had already pointed out in the 1900s that the rock art was affected by weathering, and by the mid-1960s several cases of vandalism had occurred. Surveys in the 1970s concluded that the situation was about to reach a critical stage, and therefore it was urgent to find countermeasures.

During the National Rock Art Project, initiated by the Directorate for Cultural Heritage (1996 – 2005) a renewed focus was given to the site, choosing a series of approaches with the aim of identifying what was causing the rock to break down and the destruction of the images. During the project, a number of parameters documenting climate factors and the development of vegetation, as well as chemical and biological degradation, were sampled and analysed. Active research also began to identify the best methods for protecting and conserving the rock art. This involved a detailed analysis of all of the previous documentation and comparisons with the present situation. This led to an intensive and prolonged search to locate the panels and images that the former archaeologists had documented, which had become overgrown, weathered or were in need for conservation. It became clear that neither the Cultural Heritage Act nor Vingen as a Protected Landscape was sufficient to prevent damage and vandalism at the site. In 2001 a more permanent protection of the area was established, which prohibited access by the public without authorized guides.

During the years of the rock art project and later in the 2000s, a series of archaeological excavations were carried out which have provided us with valuable additional information on how the area was used in prehistory. Together with palynological investigations, radiocarbon results have convincingly dated the activity in the area to the timespan between 4200-4900 cal BC.

In the same way as the protection of Vingen and cultural heritage in general have become more developed, the same is true of industrial development and national infrastructure, which regularly interfere with each other. The rock art site has survived small scale farming activity for a couple of centuries, and has also managed to elude a water power plant being erected at the site. Today, there are even efforts being made by some governmental institutions to try to re-establish the waterfall in the area, by keeping a minimum amount of water flowing down its natural path. The irony is that at the same time as the environmental factors in the area are being altered to return the site to a more original state, we see new threats from both the rock quarrying industry, windmill plants, and more modern infrastructure which is supported by other Norwegian governmental departments. National legislation may therefore not be powerful enough to keep industry at a suitable distance in the future, meaning that an international focus may be needed. It therefore seems necessary to focus the world’s attention on the quality of the sources and both the natural and cultural preservation of the elements in the area, something which may be more effectively secured with the help of the UNESCO.

"It is important to raise awareness of the danger Vingen's rock art is facing. You can share this page and others from the 'Vingen Links' found below to let others find out. Your voice is important. You can also sign the petition to halt this develpment, by clicking here.

→ Vingen Rock Art In Norway - Index

→ Film: Vingen Rock Art in Norway

→ Paul Taçon - Griffith University letter

→ Norway's Vingen Rock Art Petroglyphs at Risk

→ ICOMOS Statement on Vingen

→ Knowing when to back down: The plight of the Vingen rock art site, western Norway

→ Norway preserves world heritage abroad but not in Norway?

→ Vingen - A Century of Rock Art Research & Cultural Heritage

→ History of Vingen Rock Art in Norway

→ Valuing Cultural Heritage

→ Norway's Confusing Messages

→ Members and affiliated institutions of the Rock Art Network

→ Film: Vingen Rock Art in Norway

by Bradshaw Foundation

20/02/2024 Vingen Recent Articles

NORWAY

→ Knowing when to back down: The plight of the Vingen rock art site, western Norway

by George Nash

4/03/2024

→ Norway preserves world heritage abroad but not in Norway?

by Bradshaw Foundation

20/02/2024

→ Valuing Cultural Heritage

by Ben Dickiins

20/02/2024

→ Norway's Confusing Messages

by Peter Robinson

20/02/2024

→ Paul Taçon - Griffith University letter regarding the Aksla quarry and Inste Bårdvikneset quay developments in Norway

by Paul Taçon

13/02/2024

→ Norway's Vingen Rock Art Petroglyphs at Risk

by Rock Art Network

13/02/2024

→ Professor Benjamin Smith President, ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Rock Art calls for an immediate review of the decision to allow a rock quarry and a shipping quay to be built at one of the most significant rock art sites in Europe: Vingen.

by Rock Art Network

8/02/2024

→ Vingen - A Century of Rock Art Research & Cultural Heritage

by Trond Lødøen / Ben Dickins

6/02/2024

→ History of Vingen Rock Art in Norway

by Trond Lødøen

1/01/2018

→ Knowing when to back down: The plight of the Vingen rock art site, western Norway

by George Nash

4/03/2024

→ Norway preserves world heritage abroad but not in Norway?

by Bradshaw Foundation

20/02/2024

→ Valuing Cultural Heritage

by Ben Dickiins

20/02/2024

→ Norway's Confusing Messages

by Peter Robinson

20/02/2024

→ Paul Taçon - Griffith University letter regarding the Aksla quarry and Inste Bårdvikneset quay developments in Norway

by Paul Taçon

13/02/2024

→ Norway's Vingen Rock Art Petroglyphs at Risk

by Rock Art Network

13/02/2024

→ Professor Benjamin Smith President, ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Rock Art calls for an immediate review of the decision to allow a rock quarry and a shipping quay to be built at one of the most significant rock art sites in Europe: Vingen.

by Rock Art Network

8/02/2024

→ Vingen - A Century of Rock Art Research & Cultural Heritage

by Trond Lødøen / Ben Dickins

6/02/2024

→ History of Vingen Rock Art in Norway

by Trond Lødøen

1/01/2018

Friend of the Foundation

→ Knowing when to back down: The plight of the Vingen rock art site, western Norway

by George Nash

4/03/2024

→ Norway preserves world heritage abroad but not in Norway?

by Bradshaw Foundation

20/02/2024

→ Valuing Cultural Heritage

by Ben Dickiins

20/02/2024

→ Norway's Confusing Messages

by Peter Robinson

20/02/2024

→ Paul Taçon - Griffith University letter regarding the Aksla quarry and Inste Bårdvikneset quay developments in Norway

by Paul Taçon

13/02/2024

→ Norway's Vingen Rock Art Petroglyphs at Risk

by Rock Art Network

13/02/2024

→ Professor Benjamin Smith President, ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on Rock Art calls for an immediate review of the decision to allow a rock quarry and a shipping quay to be built at one of the most significant rock art sites in Europe: Vingen.

by Rock Art Network

8/02/2024

→ Vingen - A Century of Rock Art Research & Cultural Heritage

by Trond Lødøen / Ben Dickins

6/02/2024

→ History of Vingen Rock Art in Norway

by Trond Lødøen

1/01/2018

Friend of the Foundation