First brought to the world's attention in 1915 in Scientific American, the site in KwaZula-Natal is one of the best preserved in southern Africa. This central frieze contains a multitude of eland - Africa's largest antelope and the most powerful and evocative of all San symbols.

The eland is the most frequently depicted animal in many regions of southern Africa. It is also the animal upon which San artists lavished most care. They painted eland in a great variety of postures and from various perspectives, embellishing them with the finest details.

San rock art was much more than the communication of knowledge; many of the paintings were storehouses of the supernatural potency that shamans harnessed for their cosmological journeys. The rock on which the images were painted was like a veil suspended between this world and the spirit world.

The healing dance performed by San shamans to find and cast out sickness starts at night and carries on until dawn the next day. As well as living dancers, it was believed that the dancers were also attended by grotesque spirits of the dead.

The dance starts with a few women singing snatches of songs that are different from ordinary recreational songs. These special medicine songs contain n/om, a supernatural potency that permeates the cosmos but that resides particularly in large animals, such as giraffe and eland, and in the shamans themselves. Some San paintings are part human - part animal; these creatures are known as therianthropes, depicting dancers/shamans who have taken on the potency of a particular animal.

Soon the men start dancing around the women who have seated themselves in a tight circle around a central fire. The shamans push themselves towards an altered state of consciousness; they enter 'half-death'. They attain ecstasy simply by means of their dancing, concentration and hyperventilation, with the help of the women's insistent and rhythmic singing and clapping.

In half-death the shamans battle with malevolent spirits of the dead, who come to the dance and try to shoot small, invisible, 'arrows-of-sickness' into people. Attracted by the beautiful singing and dancing, the spirits lurk in the African night beyond the small circle of firelight. Balanced precariously on the edge of oblivion, experienced shamans move from person to person, laying hands on them and drawing known and unknown ills out of them. Then with a high-pitched cry they cast sickness and strife back into the darkness whence they came.

Sometimes, at the height of the dance, when the atmosphere is charged with n/om and the world is beginning to spin, some of the shamans fall unconscious in trance, sometimes casting themselves headlong into the fire. Their spirits have left their bodies on a dangerous, frightening and painful mission to protect their people. The most powerful shamans reach the terrifying abode of god himself, and there they remonstrate with him, pleading for the lives of any who may be critically ill.

People care for shamans who have entered trance, rubbing them with sweat and flicking them with flywhisks to deflect approaching arrows-of-sickness. Later, the unconsciousness of deep trance fades into natural sleep and the dance breaks up. In the morning, life goes on - cleansed - and the people, united by the great cathartic experience of the dance, return to the real life world of hunting and gathering.

Dying eland are common in San rock art. The explanation for this lies in the fact that the San word for dying is the same as the San word for entering deep trance. Many San painters depicted dying eland in close association with 'dying' dancers. The experiences of trembling, sweating and bleeding from the nose before finally collapsing were common to both; beyond this the eland was the supreme source of the potency sought by San dancers. The San describe their experiences of out-of-body travel as like flying.

All people resort to metaphors when they try to express the ineffable and sometimes bizarre experiences of trance. Today Westerners speak of a 'trip' or a 'high'. San shamanic dances and art were similarly given form by a set of metaphors that were peculiar to their own circumstances. In San thought and art 'death' in trance is closely associated with the physical death of the eland which the San believe to have more supernatural potency than any other creature.

When a shaman 'dies', he bends forward, bleeds from the nose, trembles, sweats profusely, staggers and eventually falls unconscious. Similarly, when an eland dies, it lowers its neck so that its head sways from side to side. Its hair stands on end, blood and foam gush from its nose and mouth. It trembles violently, sweats and staggers. Finally, it collapses. Sans artists were sensitive to these parallels and painted shamans in association with dying eland.

Studying this detail, the meaning fell into place: both the eland and the man are behaving as if they are dying. The man is a shaman going into trance. He is about to leave this world for the spirit world, and he is taking on the power of the eland, the most powerful animal of all, and the god /Kaggen's favourite.

On their journey, Qing and Orpen came across many magnificent paintings in rock shelters. Orpen was so impressed that he copied several of them. He then sent these to a magazine editor in Cape town, who showed them to a Dr Wilhelm Bleek. Bleek was a German linguist who was living in Cape Town. He was studying the language of the /Xam people - a San group from the Northern Cape - at this time. When Bleek showed Orpen’s drawing of the strange looking animal to the group of /Xam San he was interviewing, they immediately saw in it 'the rain animal', and proceeded to explain its spiritual and religious significance. It was this historical explanation that began the decoding of the paintings.

It was then the work of Professor David Lewis-Williams, the South African scholar and professor of archaeology at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, threw more light on the paintings. The 'Rosetta Stone' of this rock art is located at the Game Pass Shelter in the Drakensberg Mountains. "One day, I was looking at a picture in which there was a dying eland and a man apparently holding its tail. The man had hooves, like the eland; his hair was standing out, like the eland's hair; his legs were crossed, in imitation of the eland's legs," he explained.

Studying this detail, the meaning fell into place: both the eland and the man are behaving as if they are dying. The man is a shaman going into trance. He is about to leave this world for the spirit world, and he is taking on the power of the eland, the most powerful animal of all, and the god /Kaggen's favourite.

Trance is so overwhelming that it is difficult to describe. To explain it and to help people who were not shamans to see what they had been through, the painters of rock art images looked for comparative experiences. Crossing over to the spirit world during trance could be compared to 'death'. This did not mean that they actually died, but that they believed that while they were in trance, their spirits would leave their bodies and meet others in the spirit world. 'Death' is used as a metaphor for the trance state. Trance is very much like death. Sometimes it is called 'half-death'.

Professor Lewis-Williams explained how all this suddenly made sense to him: "I saw that the dying eland was a metaphor for the dying medicine man. Shamans are said to die when they enter the spirit world through trance. And the dying eland is a source of potency (spiritual power)."

To show their experiences, the artists also used visual metaphors such as showing shamans 'underwater' and 'dead'. These capture aspects of how it feels to be in trance. The artists also show their actions in the spirit world, such as their capturing of the rain animal, their activation of potency for use in healing or in fighting off enemies or other dangerous forces. But, the art was far from just a record of spirit journeys. Powerful substances such as eland blood were put into the paints so to make each image a reservoir of potency. As each generation of artists painted or engraved layer by layer of art on the rock surfaces their expansion created potent spiritual places.

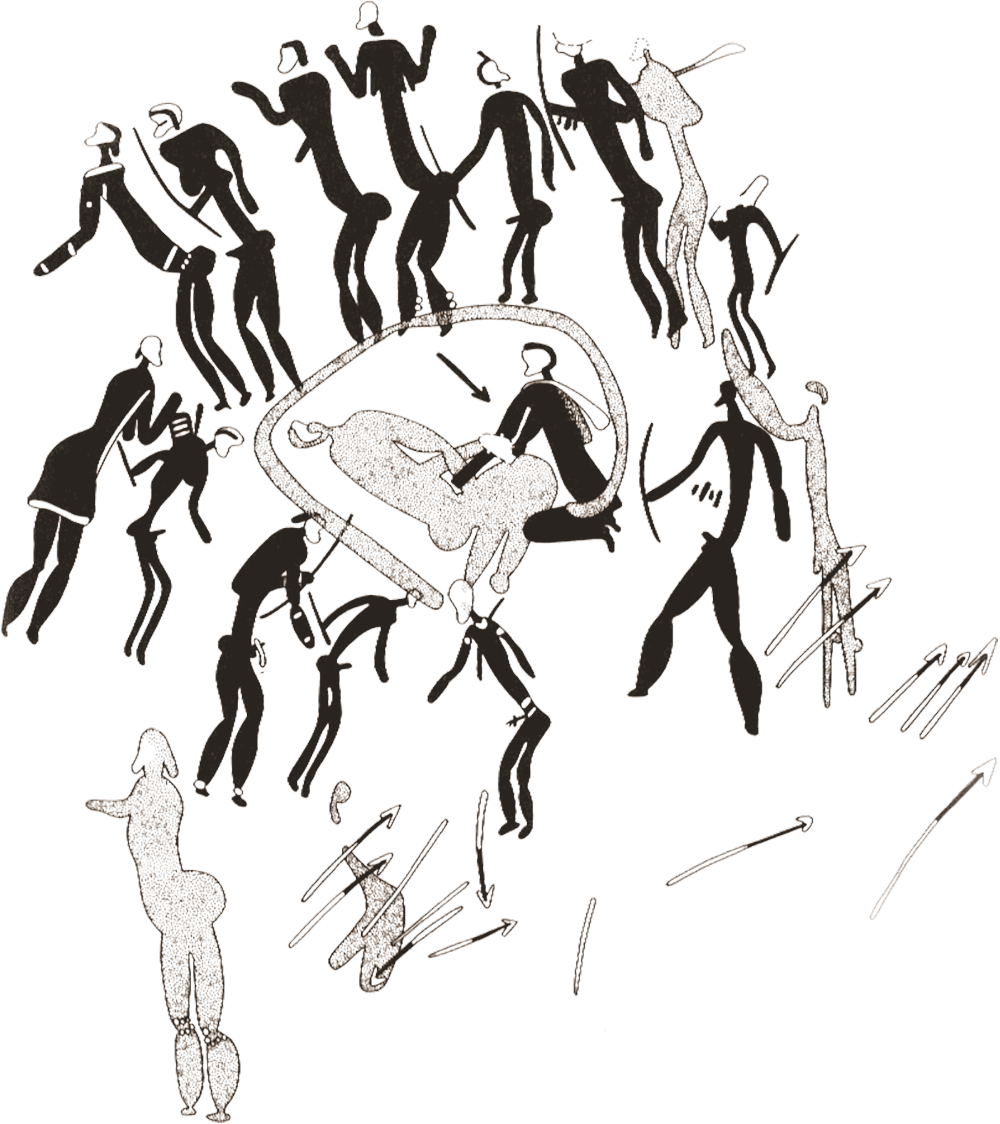

One of the San shaman's tasks was to make rain. The San thought of the rain as an animal. The shamans would capture this imaginary animal, lead it to the place where they wanted rain and kill it. Its blood and milk would then become rain. This painting, from the KwaZulu-Natal Drakensberg, shows a group of trancers in the process of capturing the "rain-bull".

Sometimes the painted dancers are shown with their bodies bent forwards so that they are almost at right angles to their legs. In this posture, they support the weight of their torsos on one or two dancing sticks. The San explain that, as the dance increases in intensity, the n/om in the shamans' stomachs starts to 'boil', their muscles contract painfully, and they bend forward in the way depicted above.

The dancers wear rattles on their legs. Scattered amongst them are a number of white flecks. Like arrows-of-sickness, these flecks probably depict something that is not seen by ordinary people. Perhaps they depict the n/om that infuses the place of the dance and that shamans can see.

→ South Africa Rock Art Archive

→ South Africa Rock Art Gallery

→ San Rock Art of the Drakensberg

→ RARI - Rock Art Research Institute

→ ARADA - African Rock Art Digital Archive

→ San Rock Art of the Drakensberg

→ Africa's World Heritage Sites

→ SARAP: Southern African Rock Art Project

→ A Map from the Memory of the World

→ Explore Cederberg rock art from your home

→ Early masterpieces: San hunter-gatherer shaded paintings of the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg

→ A Painted Treasure

→ Origins Centre

→ Animals in Rock Art

→ Reflecting Back: 40 Years Since ‘A Survey of the Rock Art in the Natal Drakensberg’ Project (1978-1981)

→ San rock art exhibition at the National Museum & Research Center of Altamira

→ Interview with Dr Ben Smith

→ African Rock Art Archive

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network