Nestled in the northern expanse of Minas Gerais, Brazil, the Peruaçu Caves National Park (Parque Nacional Cavernas do Peruaçu, or PNCP) is truly a sanctuary for biology, speleology, and archaeology. Spanning approximately 56.500 hectares, the park’s monumental karst formations and caves, as well as rock art sites, form a rich cultural and ecological mosaic that speaks to millions of years of geological forces acting upon the karst and to millennia of human history. Declared a conservation unit in 1999, the park is a land of awe-inspiring beauty, where vast cliffs, gorges, deep collapse sinks, and caves of colossal proportions are commonplace. The Peruaçu River cuts through the park, creating a vast valley and a cave system with around 180 known entrances, part of Brazil's enormous subterranean network. Concomitantly, the ancient human presence etched into rock faces dates back to almost 12.000 years ago. With its cultural and scientific wealth, Peruaçu has earned its place as a major focal point for those studying prehistoric art and the long-term relationships between ancient peoples and their unique landscapes.

What immediately distinguishes Peruaçu from most Brazilian rock-art regions is its chromatic scope and scale. While red dominates painted rock art painting elsewhere, Peruaçu’s art is fundamentally polychromatic. Red, orange, yellow, white, and black, along with intermediate tones, were produced using charcoal, manganese dioxide, iron oxides and hydroxides, calcite, and carbon. This incredibly colorful corpus of paintings is sometimes placed as high as a 6-story building, a feat which evidently required scaffolding, ropes, or climbing trees and their branches. Research in the Peruaçu region began in the 1980s under the Archaeology Sector of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG). The initial goal was to characterize the paintings and define their stylistic units. Because the valley presents a dense, synchronous superposition of images, researchers adopted a crono-stylistic approach, seeking to disentangle stylistic affinities and relative chronologies.

Excavations were carried out at several sites, including Lapa dos Bichos, Lapa do Boquete, Lapa do Malhador, Lapa do Caboclo, Lapa do Índio, and others (a side note: Lapa is Portuguese for rock wall/shelter). Among them, Lapa do Boquete was selected for systematic excavation due to its exceptional preservation of organic materials. There, occupations dated to more than 11.000 years before present were identified, along with burials containing rich funerary assemblages. A fallen block dated to more than 9.000 BP bears linear incisions, cupules, and geometric engravings, stratigraphically bracketed by hearths dated to approximately 9.350 BP below and 7.810 ± 80 BP above, which is clear evidence that engraving and painting were already embedded in early occupational phases.

The earliest occupations, around 12.000–11.000 BP, appear to have been episodic but recurrent, oriented toward technical subsistence activities rather than permanent residence. Spatial organization inside shelters, post holes, combustion structures, and concentrations of stone tool fragments suggests organized, compartmentalized use. Stone tool industries relied primarily on dark, fine-grained siliceous materials, later giving way to a broader range of local raw materials after 9.500 BP.

Pigments were present early, sometimes processed, sometimes unused, including a bone tube containing a red pigment stick, material evidence of planned painting practices. From roughly 8.000–7.000 BP onward, the function of shelters shifted. Burials appear, often accompanied by pigments, rare vegetal fibers, bone beads, tools, and stone slab coverings. Children are found in secondary burials, and their remains were sometimes fully enveloped in colored pigments, while adults received tools and protective grave structures. The unusual preservation conditions of the shelters allow these mortuary practices to be reconstructed with extraordinary clarity. Between 4.000 and 2.500 BP, the archaeological record becomes sparse, possibly reflecting reduced use of the shelters or, perhaps, later sediment disturbance.

From around 3.000 BP, however, evidence suggests the emergence of agricultural practices, including subterranean storage structures (“silos”) containing burned seeds and maize. Notably, some rock paintings interpreted as cultivated plants may predate the appearance of ceramics, indicating that cultivation preceded ceramic technology in the region. After 2.500–2.000 AP, the record changes decisively. Occupation intensifies, stone tool technology diversifies, polished objects proliferate, ceramics appear, and burial practices become more varied and elaborate. Ceramics associated with both Una and Tupiguarani traditions occur, sometimes manufactured with identical clay bodies, suggesting interaction between groups, coexistence, or shared production contexts rather than rigid cultural boundaries or alternating populations.

To date, six stylistic units have been identified in the Peruaçu Valley: the São Francisco Tradition, the Agreste Tradition, the Montalvânia Complex, the Piolho de Urubu unit, the Caboclo unit, and a particularly regional and faint expression of the Nordeste Tradition. These units do not correspond directly or necessarily to ethnic groups. Instead, they represent coherent visual repertoires, shared choices of form, color, technique, and placement, reflecting cultural affinities within and across populations. The São Francisco Tradition is the most prominent and best documented, and many units are part of the São Francisco cultural horizon. It is characterized by large geometric figures, often 30–40 cm in size, frequently executed in bichromy.

The most emblematic motif type in Peruaçu is the “cartucho”: oval, flat, escutcheon-like figures filled with one color and outlined in another, a form not identified in other Brazilian stylistic units or rock art traditions. Other recurring motifs include short parallel lines, grids, nets, zigzags, lozenges, and “plain” figures. Figurative elements such as weapons, biomorphs, anthropomorphs, and zoomorphs (e.g., fish and lizards) are present but in smaller numbers. However, due to the enormous number of figures, they still account for a few hundred motifs.

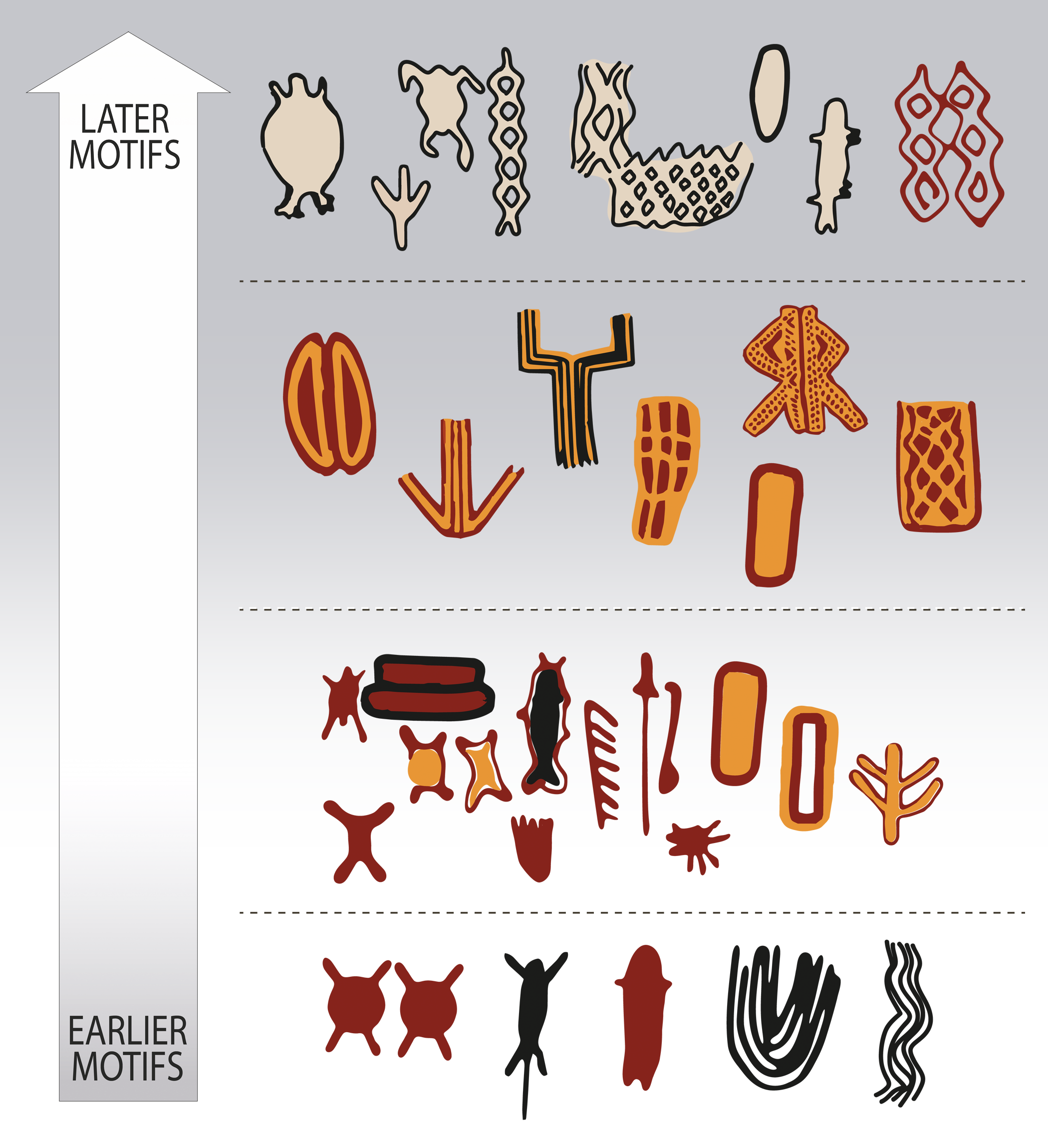

Researchers have identified four moments within the São Francisco Tradition: The first is simple and largely monochrome. The second marks the full emergence of the tradition, with extensive use of red-and-yellow bichromy and an expanded range of themes. The third reduces thematic diversity but intensifies chromatic complexity, introducing tri- and quadricolored figures (polychromy at its most whole form) and new motifs. The fourth moment represents an explosion of color use, the introduction of white made from calcite, and a renewed emphasis on “cartuchos”, nets, and lozenges, as well as other geometric forms, along with a broader range of supports and locations throughout the long valley. Across these moments, choices of site and support were clearly not random. Large, regular, vertical walls were preferred early on, often in secondary canyons or at elevated points distant from the river. Later phases expanded into irregular floors, ceilings, and previously occupied sites, indicative not necessarily of territorial expansion but of a reworking of an already meaningful landscape. Curiously, there is no rock art inside the caves, even within those that receive sunlight for kilometers, such as Janelão, thanks to clearings formed by sinkholes or collapsed ceilings that provide enough light for tropical vegetation to grow. Rock art also isn’t found in the aphotic zones of Peruaçu’s many deep caves. The colossal karst caves, in many ways reminiscent of those from the limestone plateau around the Ardèche River in France, home to Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc, might have seemed an obvious site for paintings. Yet, in almost 12.000 years, the denizens of the Peruaçu Valley apparently never ventured into the deep, pitch-dark recesses of these caves. The reasons may remain forever unknown. Perhaps the staggering abundance of brown recluse spiders, among the deadliest in the world, inside all caves acted as a deterrent. Yet it is almost certain that these prehistoric populations possessed their own understanding of the subterranean world, which decisively shaped their choice not to paint in the cave depths.

It is almost a truism that rock art is one of the principal means through which landscapes are constructed. As visual interventions, paintings and engravings reshaped how space was perceived, remembered, and revisited, effectively rewriting rock surfaces and materializing relationships between people and place. In the Peruaçu Valley, these practices actively configured the landscape, transforming rock shelters, canyon walls, and cave entrances into socially meaningful places and embedding human presence within the valley's geological fabric. From this perspective, the São Francisco Tradition and the Montalvânia repertoires present at Peruaçu are best understood as components of a single, long-term system of landscape marking rather than as just stylistic traditions tied to bounded social groups.

Differences, primarily in technique and spatial setting, reflect varied ways of engaging with specific locations. At the same time, shared bodily modes of execution and viewing, thematic associations, and the use of rock supports point to overlapping practices and audiences. The absence of a secure chronological sequence among the multiple styles converging at Peruaçu reinforces an interpretation of recurrent, contemporaneous engagement with the same places, rather than of linear stylistic replacement and/or succession. Although clear diachronic relationships are evident within the São Francisco styles through systematic superimpositions, these do not resolve into a simple evolutionary sequence. Instead, the frequent co-occurrence of formal and thematic attributes across São Francisco and Montalvânia corpora suggests sustained visual dialogue across sites, generations, and surfaces.

Differences between São Francisco and Montalvânia styles in panel exposure, placement, technological investment, and the relationship between themes and visibility point to differentiated regimes of viewing and participation within a shared cultural horizon. Together, the evidence supports long-term continuity, with visual practices evolving within a stable yet dynamic landscape.

The Peruaçu thus emerges not as a patchwork of disconnected occupations, but as a cumulative landscape shaped through repeated acts of marking, viewing, and reworking stone surfaces over much of the Holocene, at the intersection of the Caatinga, Cerrado, and Atlantic Forest biomes and within the constraints and possibilities of a distinctive karst environment.

The Peruaçu thus emerges not as a patchwork of disconnected occupations, but as a cumulative landscape shaped through repeated acts of marking, viewing, and reworking stone surfaces over much of the Holocene, at the intersection of the Caatinga, Cerrado, and Atlantic Forest biomes and within the constraints and possibilities of a distinctive karst environment.

At the site known as Lapa dos Desenhos, literally, “Shelter of the Drawings”, the rock art of Peruaçu Caves National Park reveals its full expressive range, both in stylistic variation and in the diversity of techniques employed. The central panel, extending for several dozen meters in length and rising nearly ten meters in height, contains thousands of individual motifs. These range from abstract and geometric patterns to the distinctive cartucho motifs, compact, closed forms with filled interiors, often rendered in polychrome, and to figurative representations of animals and plants, most commonly painted in black. Among the zoomorphic figures, fish, birds, and lizards occur with particular frequency, suggesting that this segment of the surrounding fauna held distinct symbolic importance. Some panels at Lapa dos Desenhos were placed unbelievably high and necessitated perilous climbing, which could, in theory, indicate that rock art making was, at some meaningful level, associated with feats of dexterity and physical prowess.

Excavations at the Lapa do Boquête site yielded radiocarbon dating indicating human occupation dating back almost 12.000 years before present. Furthermore, six burials were identified, dating to around 7.000 years before present, along with stone artifacts and structural features interpreted as habitation remains. The site preserves rock art panels combining both paintings and petroglyphs, comprising geometric designs as well as zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures. Of particular interest is the large red Caboclo motif, along with a myriad of geometric designs in red, orange, purple, yellow, and black.

The painted figures locally referred to as “caboclos” constitute a class of anthropomorphic representations defined by recurring formal features, indicating a distinct motif type within the broader corpus of human imagery. In Brazilian popular culture and the Portuguese language, the term is full of nuance, as “caboclo” carries layered meanings: it may denote a person of mixed ancestry, often associated with Indigenous ancestry, and, in religious and symbolic contexts, it also refers to forest-associated enchanted spirits. While these later meanings cannot be projected directly onto the prehistoric imagery, they nonetheless illuminate the symbolic resonance the term has acquired in local interpretive traditions.

Here, the caboclo first seen in red at Lapa do Boquete reappears as the central figure, now rendered in black. Its visual dominance is such that it lends its name both to the site and to the distinctive stylistic unit defined by its associated corpus of motifs: highly developed, internally coherent, and specific. Surrounding the prominent caboclo figure, a dense array of cartucho-type motifs is superimposed in a striking composition on an exceptionally flat rock wall, a surface particularly well suited to painting. In São Francisco rock art studies, the term cartucho is used descriptively to refer to closed rupestrian motifs with fully filled interiors, named for their compact, self-contained appearance. While cartucho motifs occur elsewhere, their most highly developed forms are, to date, restricted to Peruaçu National Park.

The most expressive cartouches of

the Peruaçu Valley, Lapa do Caboclo.

The Janelão (“big window”) is the principal attraction of Peruaçu National Park. Its scale is immediately striking, expressed in a large mouth, vast dolines, immense chambers, and monumental speleothems. The cave is home to the largest stalactite ever recorded, known as “The Ballerina’s Leg”, a staggering 28 meters in length, 2 meters shorter than the famous Christ the Redeemer statue, in Rio de Janeiro. The cave itself is 8 km long and has a vertical range of 180 meters. A series of natural skylights allows sunlight to penetrate the cave, creating small interior groves. The Peruaçu River runs through the entire cave and is one of its most distinctive features.

At the cave’s entrance, a towering rock wall forms an open-air panel, where extensive rock art compositions can be observed. Known as the Janelão atelier, these rock art panels are placed approximately 3 meters high and are notable for their bold, striking colors. From the Atelier, a large doline functions as a natural window, offering panoramic views of the cave entrance and the first of several skylights. These punctuate approximately 3.5 kilometers of passages adorned with stalactites, stalagmites, and numerous rare speleothemes, made all the more remarkable by their visibility in full daylight thanks to collapsed sections of the ceiling.

Analytical studies of pigment samples from the Janelão rock art indicate the presence of disordered hematite, a mineralogical pattern that can resemble goethite heated to temperatures between approximately 250 and 600 °C. This raises the possibility that pigments may have been intentionally thermally transformed prior to application. However, similar mineralogical signatures were also observed in natural samples collected from the surrounding environment, and comparable alterations can result from weathering and other post-depositional processes. Consequently, while thermal treatment of pigments cannot be ruled out, the available evidence does not allow this practice to be identified with 100% confidence.

The Peruaçu Park was inscribed in 2025 as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its karstic landscape, including its extensive cave systems, monumental underground galleries, and the world's largest stalactite. These features are undeniably impressive and more than sufficient to justify recognition as a protected natural monument, or even as a UNESCO Global Geopark. As a landscape of exceptional beauty and geological interest, Peruaçu clearly merits international attention. Yet World Heritage status demands more than “just” scenic grandeur. It is intended to recognize places of outstanding universal value because they reveal something distinctive about the human or natural past. In this respect, Peruaçu’s natural attributes, however spectacular, are not unique in themselves. Karst cave systems of comparable scale, complexity, and beauty exist in many parts of the world.

What is singular at Peruaçu is not the presence of gorgeous caves, but the dense and varied archaeological record embedded within them and across the surrounding landscape. The strictly natural framing of the park reduces the site to a collection of geological superlatives, while marginalizing the very features that make Peruaçu irreplaceable. The valley contains a remarkable concentration of rock art panels, archaeological deposits, and material traces of long-term Indigenous engagement with the karst, evidence that is not interchangeable with that of other cave systems. These cultural remains are not incidental additions to a natural setting; they are integral to how the landscape was perceived, navigated, and rendered meaningful over millennia.

The iconic black bird, one of the park's symbols, depicted at Lapa dos Desenhos.

The issue, therefore, is not that Peruaçu was wrongly inscribed, but that it was incompletely inscribed. Its natural values alone justify protection. What remains absent is the formal acknowledgment that the site’s most distinctive qualities lie in the intersection of geology and human presence. How, one is tempted to ask, has this magnificent corpus of rock art been relegated to the status of a quaint footnote, an “interesting and peculiar” addendum, rather than recognised as one of the very reasons the site merits World Heritage status at all? Rock art is hardly an archaeological garnish or a charming eccentricity; it is the most intentional, eloquent, deliberate, and consequential form of ancient human intervention in the landscape.

Happily, UNESCO’s own mechanisms allow for such a much-needed and desired recalibration, whether through re-nomination, supplementation of the dossier, and recategorization to reframe its recognition as that of a mixed property. Revisiting Peruaçu’s status would not, of course, diminish its standing. On the contrary. It would strengthen it by aligning institutional categories with reality and recognizing that Peruaçu is not only a beautiful karst landscape but also a uniquely human one.

For those interested in this fantastic rock art complex, the Brazilian National Center for Cave Research and Conservation (ICMBio/Cecav) has created a free, online 3D immersive experience that lets visitors explore a variety of caves, geological features, and archaeological sites in the Peruaçu National Park.

- de Faria DLA, Lopes FN, Souza LAC, Branco HD de OC. Análise de pinturas rupestres do Abrigo do Janelão (Minas Gerais) por microscopia Raman. Quím Nova [Internet]. 2011;34(8):1358–64. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-40422011000800012

- Soares, Carlos Eduardo V. Aldighieri. "O espaço pictórico do Peruaçu: linguagem visual e leitura social."

- Isnardis A. Pintar como relação: interações entre pessoas e pinturas nas paredes de pedra. Bol Mus Para Emílio Goeldi Ciênc hum [Internet]. 2024;19(1):e20220082. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/2178-2547-BGOELDI-2022-0082

- Vitral, José Roberto Câmara. "Pinturas Rupestres do Sítio Arqueológico A Toca do Índio." Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfi co de São João del-Rei: 42.

- Prous, A. (2019). Uma visão panorâmica da arte rupestre do Brasil. SOCIEDADES DE PAISAJES ÁRIDOS Y SEMIÁRIDOS., 12(1-2), T2-17.

- RIBEIRO, Loredana. Repensando a tradição: a variabilidade estilística na arte rupestre do período intermediário de representações no alto-médio rio São Francisco. Revista do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia, n. 17, p. 127-147, 2007.

- Ribeiro, L. (2008). Contexto arqueológico, técnicas corporais e comunicação: dialogando com a arte rupestre do Brasil Central (Alto-Médio São Francisco). Revista de arqueologia, 21(2), 51-72.

- Ribeiro, L. (2006). Os significados da similaridade e do contraste entre os estilos rupestres – um estudo regional das gravuras e pinturas do Alto-Médio Rio São Francisco. Tese de Doutorado, Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia, Universidade de São Paulo.

- Prous, A., Junqueira, P. A., & Malta, I. M. (1984). Arquelogia do Alto Médio São Francisco Região de Januária e Montalvânia. Revista de Arqueologia, 2(1), 59-72.

- Prous, A., & Baeta, A. M. (2001). Arte rupestre no vale do Rio Peruaçu. Aspectos gerais. O Carste, 13(3), 152-158.

- Prous, A. (1991). Arqueologia brasileira (pp. 613p-613p). Brasília: Editora Universidade de Brasília.

- Gaspar, M. (2003). A arte rupestre no Brasil. Editora Schwarcz-Companhia das Letras.

- Justamand, M., Martinelli, S. A., de Oliveira, G. F., & de Brito, S. D. (2017). A arte rupestre pelo olhar da historiografia brasileira: uma história escrita nas rochas. Revista Arqueologia Pública, 11(1 [18]), 130-172.

- Horta, A. I., & Afonso, M. C. (2004). Lapa, parede, painel: distribuição geográfica das unidades estilísticas de grafismos rupestres do Vale do Rio Peruaçu e suas relações diacrônicas (Alto-Médio São Francisco, Norte de Minas Gerais).

- Isnardis, A. (2004). Lapa, parede, painel: distribuição geográfica das unidades estilísticas de grafismos rupestres do vale do rio Peruaçu e suas relações diacrônicas (Alto-Médio São Francisco, Norte de Minas Gerais) (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil.

- Linke V, Alcantara H, Isnardis A, Tobias Júnior R, Baldoni R. Do fazer a arte rupestre: reflexões sobre os modos de composição de figuras e painéis gráficos rupestres de Minas Gerais, Brasil. Bol Mus Para Emílio Goeldi Ciênc hum [Internet]. 2020;15(1):e20190017. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/2178-2547-BGOELDI-2019-0017

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ Brazil Rock Art Archive

→ The Lajedo de Soledade

→ The Rock Art of Pedra Grande

→ the Rock Art of Serrote do Letreiro

→ The Ingá Rock

→ The Peruaçu National Park

→ The Poty River Canyon Petroglyphs

→ Rock Art of Serra da Capivara

→ Rock Art of Pedra Furada

→ The Rock Art of Santa Catarina

→ South America Rock Art Archive

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network