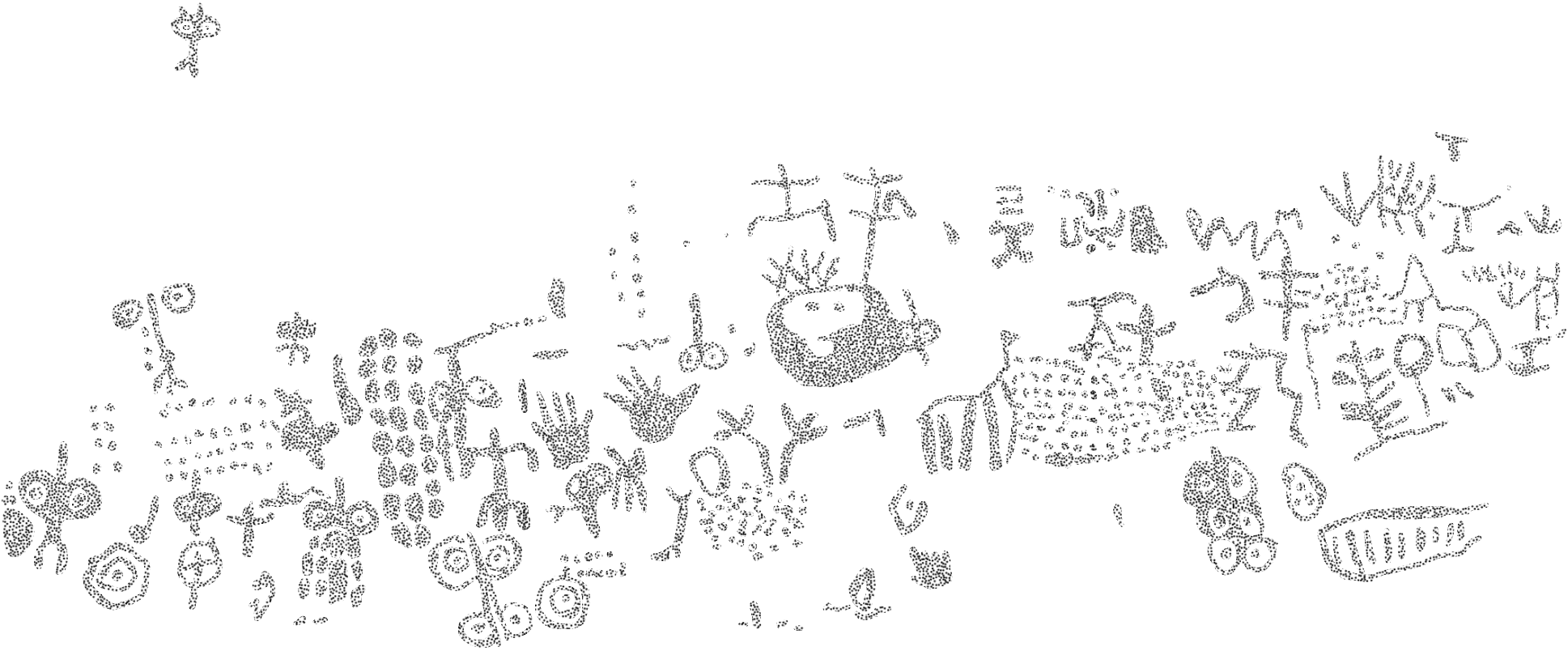

The Poty River Petroglyphs represent one of the most extensive and visually intricate engraved assemblages anywhere in the country. Executed through fine pecking and abrasion, the carvings are geometrically precise, rhythmically composed, and perceptually harmonious. Motifs include concentric circles, parallel lines, meandering forms, cupules, and occasional figurative shapes resembling reptiles, primates, and anthropomorphic figures. Their technical consistency and visual coherence reveal advanced symbolic and visual organization.

Virtually absent from colonial records, the site remained known only to local inhabitants until the 1990s, when Conceição Lage and a team from the Federal University of Piauí first visited the area and brought it to scholarly attention. In subsequent years, Wellington Lage devoted both his master’s and doctoral research to this extraordinary rock art corpus. Analyses by Lage & Lage, grounded in Gestalt perception theory, reveal the artists’ deliberate use of visual principles such as symmetry, proximity, and continuity. The engravers transformed the canyon’s sensuous and sculptural stones into a rhythmic field of forms, each panel a meditation on order, flow, and balance.

The outstanding value of the Poty River Petroglyphs lies in their continuity. They are not scattered concentrations of engravings separated by distance, but an unbroken sequence of symbolically charged interventions along the river’s flanks. For three kilometers, during the dry season when the water level lowers and the rocks emerge, the canyon becomes a vast open-air gallery where scarcely a boulder remains untouched by human hands. Moving through it invites constant crossings, crawling, bending, jumping over, climbing, and kneeling, to discover more figures hidden behind curves in the rock, beneath ledges, or fully exposed to the sun. Far from random or isolated, these petroglyphs form a unified artistic-archaeological field and symbolic landscape. Given the extent of the engraved area, its “completion” may have taken decades, if not centuries.

The petroglyphs’ placement near natural water tanks (tanques in Portuguese) suggests activity tied to water cycles or ritual and shamanic practices. The engravers must have been fully aware that the images would be seasonally submerged, yet they engraved there, following a remarkably consistent grammar of form, technique, and composition. The result is a landscape imbued with meaning, unique in its scale, formal refinement, and integration with the geomorphological setting. The petroglyph tradition of the Poty River Canyon is unparalleled in Brazil for its formal complexity, thematic richness, and scale. Nowhere else in the country does such a continuous, large-scale petroglyph complex exist. Further, it is undoubtedly among the most extensive and cohesive engraved ensembles in the world, both in terms of density and surface area. It represents the distinctive imagery of an ancient human group who, apart from a few scattered stone points, left no other trace of their passage, only this mesmerizing visual record carved into the very body of the Poty River.

The canyon is so densely covered with motifs that it is often difficult to discern where one panel ends and another begins, each expressing the tradition’s distinct formal and symbolic character. Yet, within this vast continuum, specific groupings of motifs or distinctive rock formations stand out. Four panels, in particular, perfectly embody this site’s spirit and its conceptual sophistication:

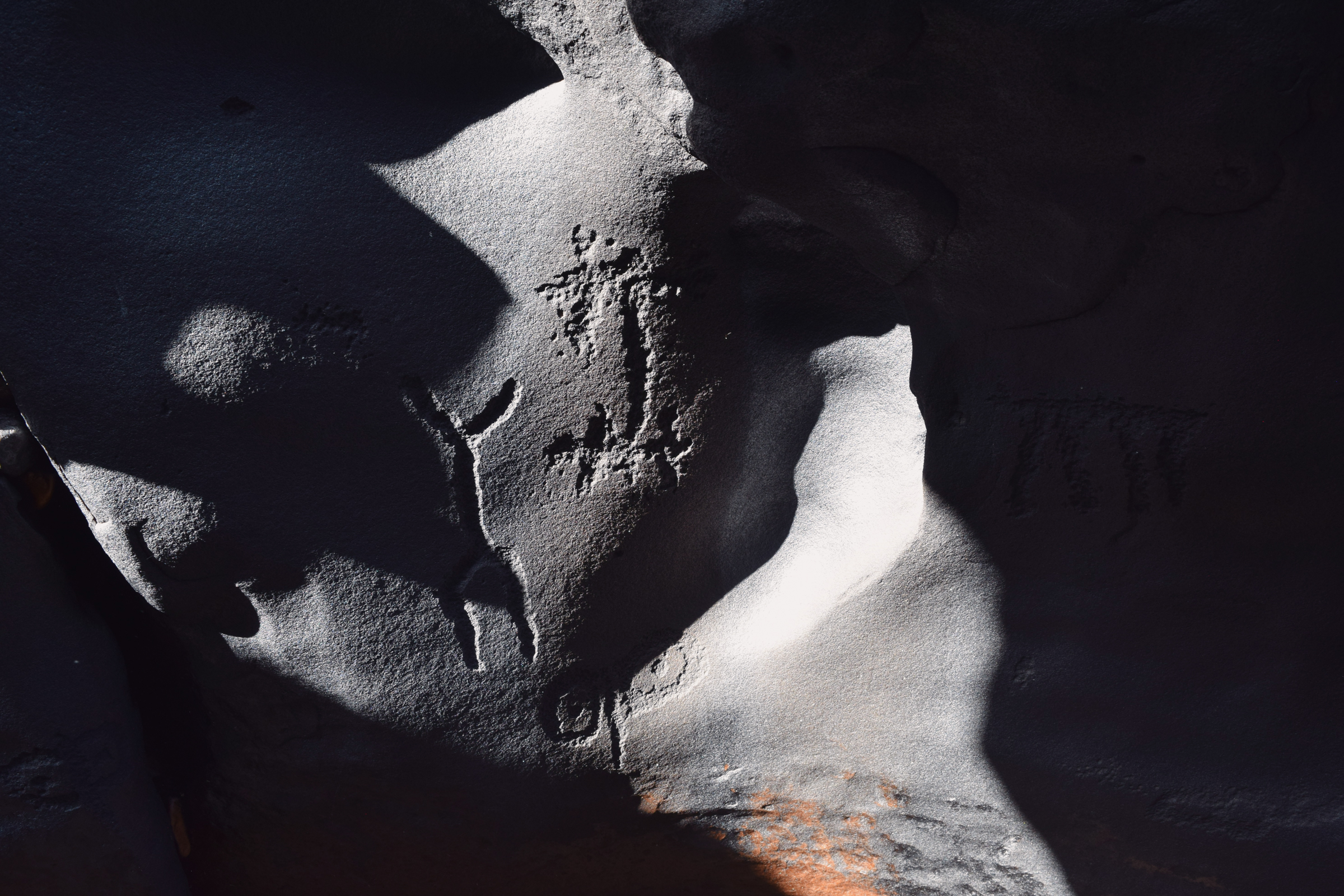

Located on the southern portion of the eastern bank, this monumental and unusually flat rock block measures approximately 4.30 m in length by 2.30 m in height. Positioned just above the riverbed, it endures continuous erosion, fissuring, and material loss from both surface runoff and fluvial action. The surface bears an impressive density of engravings, geometric, figurative, and abstract, executed with varied techniques.

The petroglyphs are almost hieroglyphic in appearance, which may lead the more incautious observer to assume they represent some form of pre-colonial writing, an interpretation for which no evidence presently exists. Worse still, and in keeping with a pseudoarchaeological tradition fashionable in the nineteenth century and regrettably experiencing a revival today, would be to attribute them to ancient lost civilizations such as Atlantis, or to supposed visits by ancient Greeks or Phoenicians.

Its scale and complexity set the Monumenal Panel No. 1 apart from most other panels in the canyon, establishing it as one of the visual and symbolic nuclei of the site. Despite centuries of weathering, the composition remains remarkably cohesive, unified into a single, intelligible visual field.

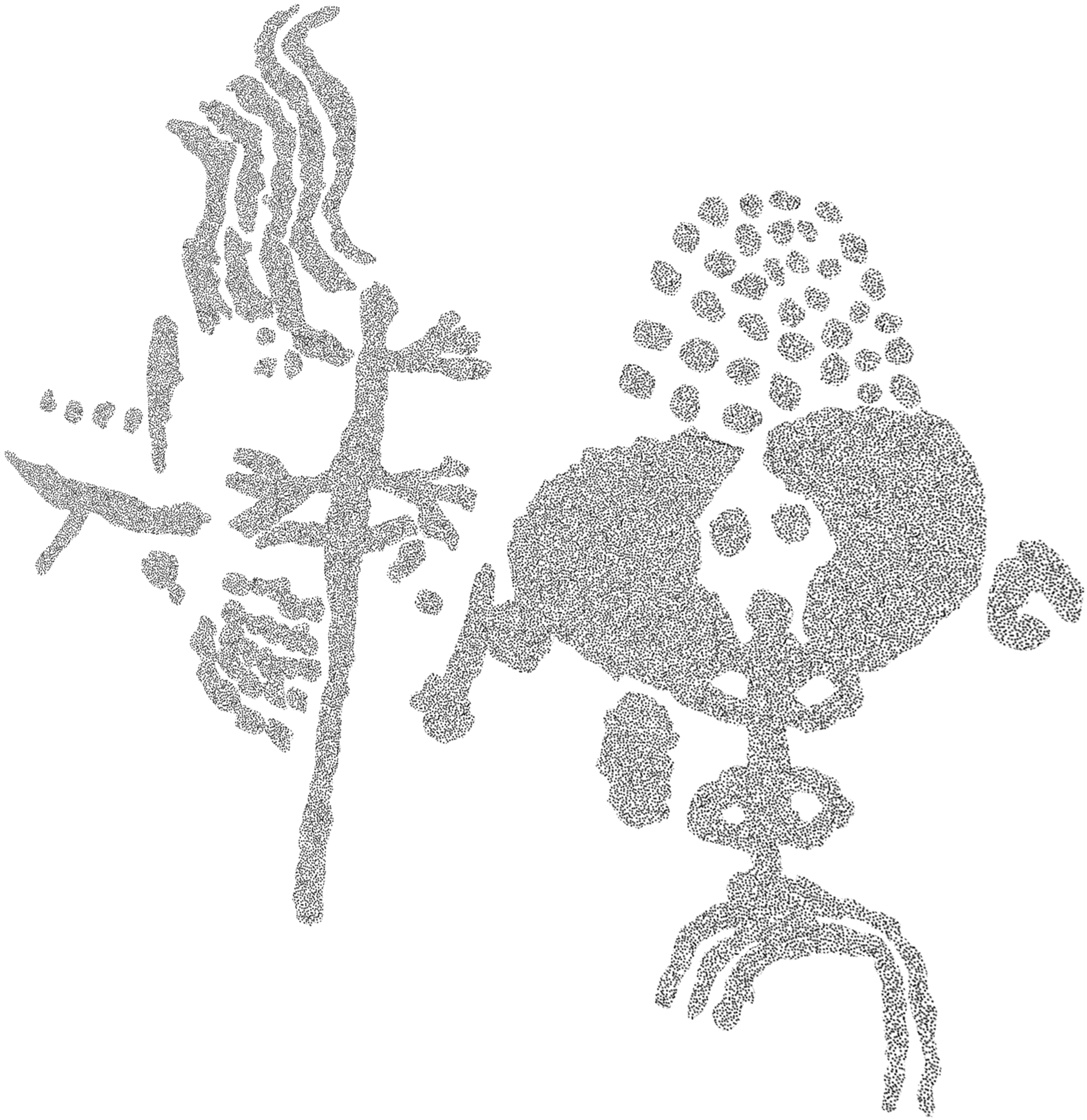

Carved on a “whale-shaped” boulder along the riverbank, this panel presents a prominent zoomorphic figure locally known as the Monkey or the Mask. Its expressive outline, partly human, partly animal, suggests a liminal being, perhaps a guardian spirit, though its true meaning will likely remain unknown. Surrounding the central motif are geometric engravings and a stylized lizard, arranged with deliberate balance. The artists skillfully incorporated the boulder’s natural curves into the design, revealing a refined understanding of the rock’s plastic qualities and its role as an active element within the composition. Indeed, such intelligent use of the surface is far from uncommon in the Poty River Canyon, quite the contrary. It appears to be a canonical trait of this rock art tradition, one seemingly confined to a single site. Yet what it lacks in the number of sites, it more than compensates for through the scale and grandeur of this singular, larger-than-life locus of meaning investiture.

An isolated, chair-shaped block measuring 1.50 m in height and 1.10 m at the base, “The Throne” is fully engraved on its frontal face, predominantly with cupules. Despite severe erosion on its upper and lower right sections, the engravings retain remarkable legibility. The sharpened edge on the right side, together with the color difference and the abrupt interruption of the engraved composition, suggests that the “throne” was broken during a submersion event, with its missing portion likely struck by debris carried in the current and subsequently swept downstream. This unfortunate incident probably occurred a couple of decades, if not centuries ago. The color contrast and sharpness of the fracture indicate a relatively recent loss, yet the edge and the surface have already been partially smoothed by water, a process that requires countless episodes of submersion. The Throne, despite being hewn from solid rock, is not indestructible. This fact only magnifies the need for photogrammetric recording and digital preservation (to be discussed subsequently), as each rainy season carries the risk of irreversible damage.

The surface composition of the Throne forms a structured, harmonious visual field: sequences of cupules create ascending and descending movements, while aligned groups produce a sense of symmetrical balance. Specific figures illustrate visual rhythm and perceptual tension. The interplay of ordered and vestigial forms reveals both deliberate design and entropy. The sheer number of engravings, the size and unusual shape of this boulder, and its prominent position low on the west margin make it a focal point in the canyon’s petroglyph landscape. However, as it lies almost at riverbed level, it is visible only when the water level is at its lowest, a condition that does not occur every year and requires an episode of extreme drought.

The engravings feature a central line flanked by paired circles, most of which contain a small dot at their centers. The pattern recalls a row of open wings, or a series of unblinking eyes. Standing before it, one has the uncanny sense of being watched. Carved with remarkable precision through percussion and pecking, the figures alternate circles and points in a steady rhythm, creating an impression of movement and quiet vigilance. The inner dots turn each circle into a gaze, forming a silent procession of eyes that seem to follow the river’s course across the dark, polished rock.

This visual duality, part butterfly, part vision, suggests perception, metamorphosis, and spiritual guardianship. So persuasive is this impression that local residents call these motifs the “River Guardians”. The images flow with the stone itself, tracing its natural curves and reinforcing the Gestalt principles of unity and continuity, as though the canyon were populated by watchful presences. In these petroglyphs, the engravers achieved a rare synthesis. The Butterfly-Eyes express the site’s material intelligence and open a dialogue between seeing and being seen: to paraphrase Nietzsche, if you gaze long into the canyon, the canyon gazes also into you.

This makes the canyon part of a rare class of fluvial rock art landscapes, where symbolic expression engages directly with the dynamics of river and stone. The petroglyphs remain undated, yet stylistic and contextual clues suggest a Holocene age. Their makers were most likely hunter-gatherer groups who followed the river as a seasonal route, leaving traces of movement, perception, and belonging on its surface, a complex and fascinating worldview etched in stone. The Poty River Canyon preserves a fragment of that lost symbolic universe, glimpsed today only through an embodied act of seeing and through our enduring need to comprehend and order reality, an effort we now carry on as archaeologists.

Open-air exposure and submersion cycles make the Poty River Canyon Petroglyphs extremely fragile. The panels suffer from exfoliation, fissuring, mineral leaching, and biological colonization. Floodwaters abrade the lower surfaces, while wind and thermal stress disaggregate grains of the sandstone matrix. Human visitation, livestock, and recent increases in tourism compound these natural threats. Preservation of the Poty River Canyon Petroglyphs demands urgent, systematic monitoring and documentation. To say that a complete 3D scan and photogrammetric record of this monumental ensemble is urgent would be an understatement. The river is a living, dynamic, and, albeit beautiful, restless system. Time, in its turn, is unforgiving. Everyone who works with rock art knows that the loss of the sites we strive so passionately to protect is never a question of if, but when. A complete digital documentation of the Poty petroglyphs has yet to be carried out, and the creation of a comprehensive management plan, one that genuinely includes local communities, remains an urgent task.

The residents of the Espírito Santo Farm, namely, the caretaker, Mr. Zé Caboclo, his wife, and his son, all born on the property, play a crucial role in protecting the site. They oversee access, prevent vandalism, and transmit traditional knowledge about the landscape and its history. Today, the entire farm is privately owned, and a luxury resort has been established roughly 500 meters south of the petroglyph zone. Mr. Zé Cabloco and his family still live there and now work for the resort. The enterprise promotes the region’s natural beauty, the rugged Caatinga biome, its pristine night skies ideal for astronomical observation, and, notably, guided visits to the petroglyphs. Though new structures now rise nearby (rooms, restaurant, pools, a little chapel, and even a helicopter landing pad), they stand far enough away for the canyon to retain an atmosphere of sacred stillness.

The resort has made a truly commendable effort to promote sustainable tourism and foster appreciation for Brazil’s archaeological heritage, which is no small achievement in a country where the economic elite seldom engage with Indigenous realities and archaeological sites are often sacrificed in the name of “progress.” Yet the absence of fundamental research and site-interpretation infrastructure remains a pressing issue: there is no museum, no local laboratory, and no interpretation center within hundreds of kilometers. Their creation is not only desirable but essential for the site’s long-term protection, research, and public engagement.

Petroglyphs remain notoriously difficult to date, leaving their chronology open to interpretation. However, a reasonable terminus post quem can be placed around 11.000 years before present, the oldest securely dated human remains in Brazil1. Excavations approximately 200 meters from the canyon’s rim, at a site linked to a lithic industry, have not yet been securely associated with the rock art record. Nonetheless, such work is essential, as prehistoric lithic industries in Brazil are comparatively well dated, and the recovery of organic materials suitable for direct dating from the excavated strata will yield critical insights into the timing and nature of human presence in the area, whether preceding or succeeding the rock art tradition.

Environmental conditions further highlight the urgency of developing replicas and an interpretation center. During the rainy season, the river’s volume rises dramatically, submerging the archaeological site entirely. The strong current carries tree trunks and large boulders that collide with the petroglyphs, fracturing them and sweeping fragments downstream. For much of the year, therefore, the site is not only vulnerable to natural damage but wholly inaccessible. Even during the dry months, access remains difficult: the terrain is rocky and physically demanding, temperatures often reach close to 40º C, and humidity is extremely low. As a result, the site is beyond reach for many visitors, particularly those with limited mobility. In this way, replicas and a dedicated museum-interpretation center are indispensable, not only to preserve and study the archaeological heritage of the Poty River Canyon but also to make it intelligible and accessible to a wider public, ensuring that this irreplaceable record of human creativity can be appreciated without endangering its survival.

- Barreto, L. L., & da Costa, L. R. F. (2014). Evolução geomorfológica e condicionantes morfoestruturais do cânion do rio Poti–Nordeste do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Geomorfologia, 15(3).

- Barros, J. S. (2022). Cânion do rio Poti: um cenário da história geológica planetária da Bacia do Parnaíba. Revista da Academia de Ciências do Piauí, 3(3).

- da Silva, H. V. M., Maia, R. P., & da Cunha, L. J. S. (2023). Aspectos culturais de locais de interesse geomorfológico (LIGeom) da região do cânion do rio Poti, Nordeste do Brasil. Physis Terrae: Revista Ibero-Afro-Americana de Geografia Física e Ambiente, 5(2–3), 247–262.

- Lage, W. (2013). As gravuras rupestres do sítio Bebidinha, Buriti dos Montes – Piauí: Documentação, análise da linguagem visual e levantamento sobre o estado geral de conservação (Dissertação de mestrado em Antropologia e Arqueologia). Universidade Federal do Piauí.

- Lage, W. (2018). Por entre rochedos bordados passa um rio: Um olhar da Gestalt para efetuar uma leitura do passado (Tese de doutorado em Arqueologia). Universidade de Coimbra.

- Lage, M. C. S. M., Lage, W., & do Nascimento, A. L. M. L. (2020). Paisagem, gravuras, problemas de conservação: Um olhar sobre o sítio Poço da Bebidinha. Revista Mosaico: Revista de História, 13(2), 152–170.

1 Although claims for pre–Last Glacial Maximum human presence have been made in Brazil, such assertions remain highly contested. Genetic evidence indicates that the peopling of the Americas occurred around 16.000 years ago, and no human skeletal remains older than approximately 11.000 (at best, 12.500 years) BP have been found in Brazil. Consequently, controversial sites such as Boqueirão da Pedra Furada, in Serra da Capivara, Piauí, and Santa Elina, in Mato Grosso, cannot be reasonably employed as reliable chronological references at the moment.

→ Subscribe free to the Bradshaw Foundation YouTube Channel

→ Brazil Rock Art Archive

→ The Lajedo de Soledade

→ The Rock Art of Pedra Grande

→ the Rock Art of Serrote do Letreiro

→ The Ingá Rock

→ The Peruaçu National Park

→ The Poty River Canyon Petroglyphs

→ Rock Art of Serra da Capivara

→ Rock Art of Pedra Furada

→ The Rock Art of Santa Catarina

→ South America Rock Art Archive

→ Bradshaw Foundation

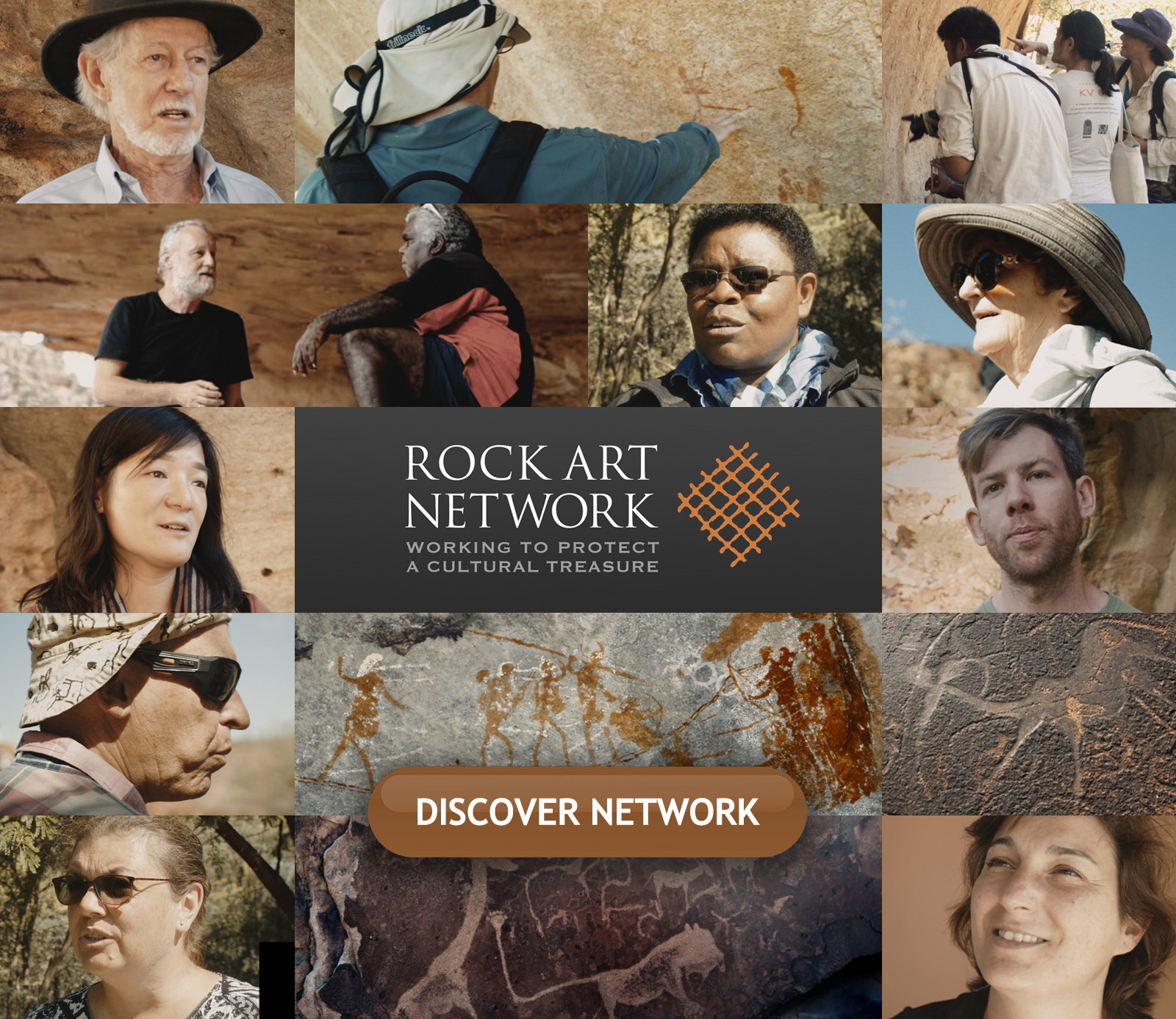

→ Rock Art Network