Adapted from Issue 51 of INORA the International Newsletter on Rock Art

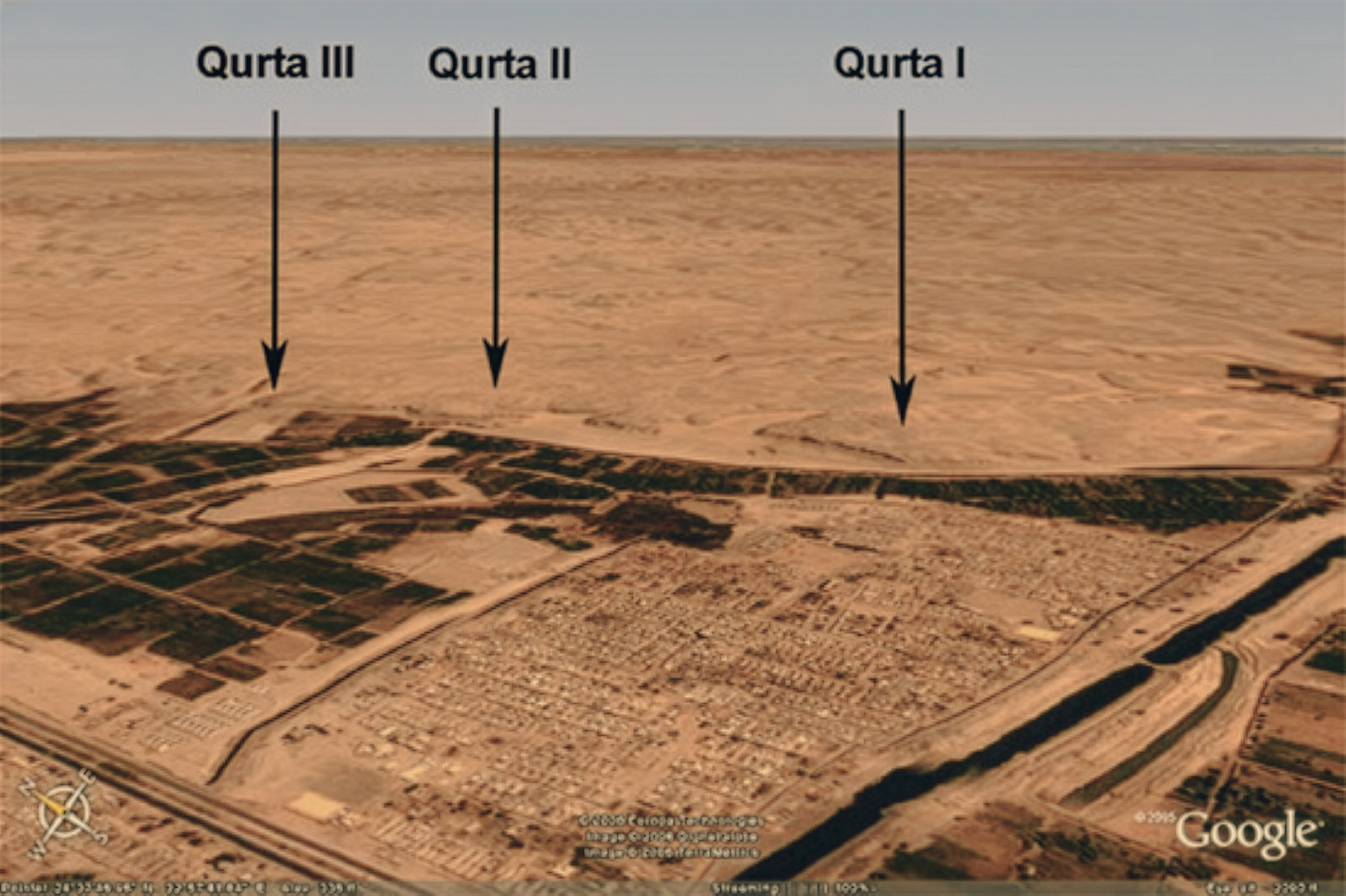

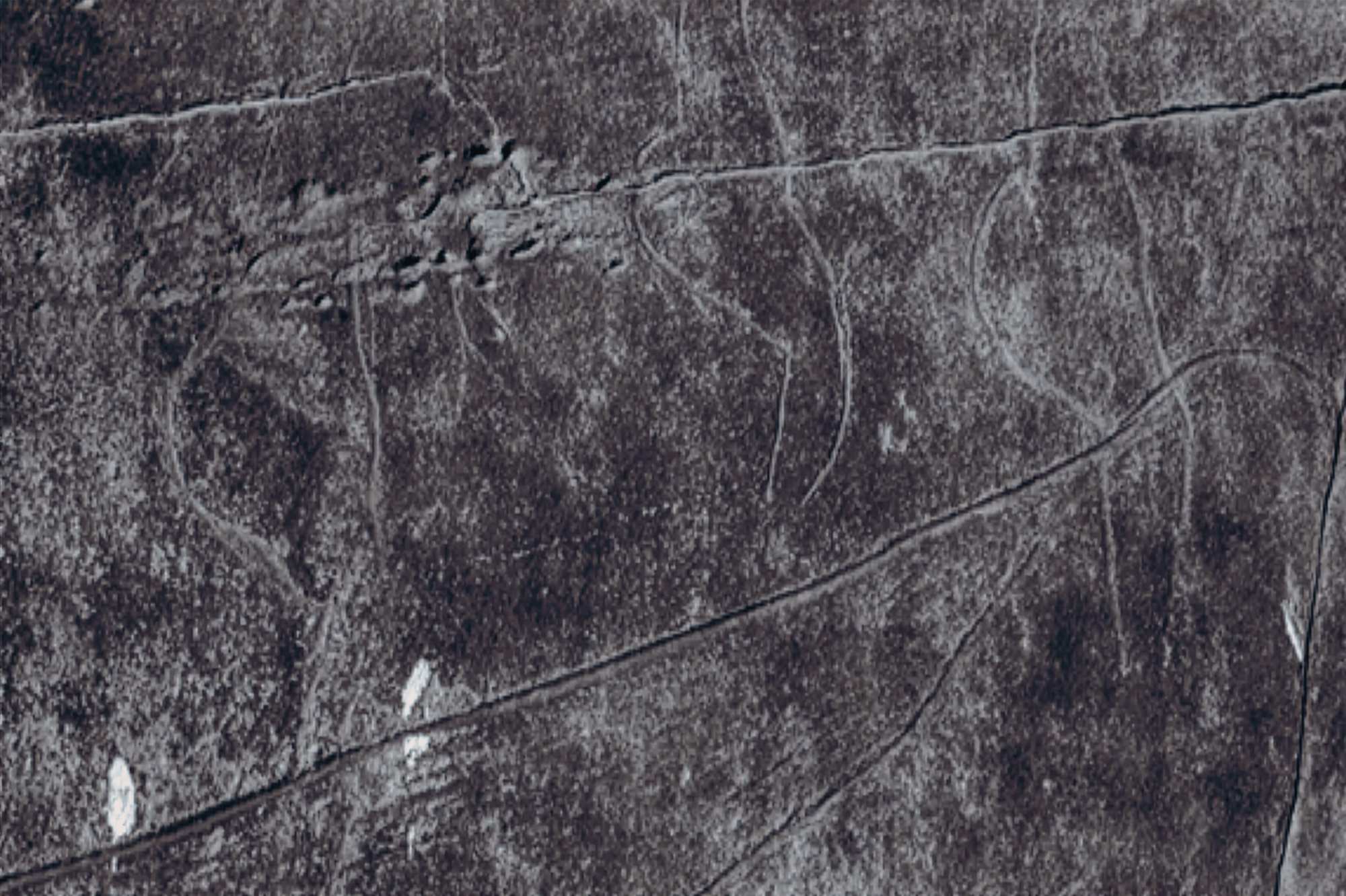

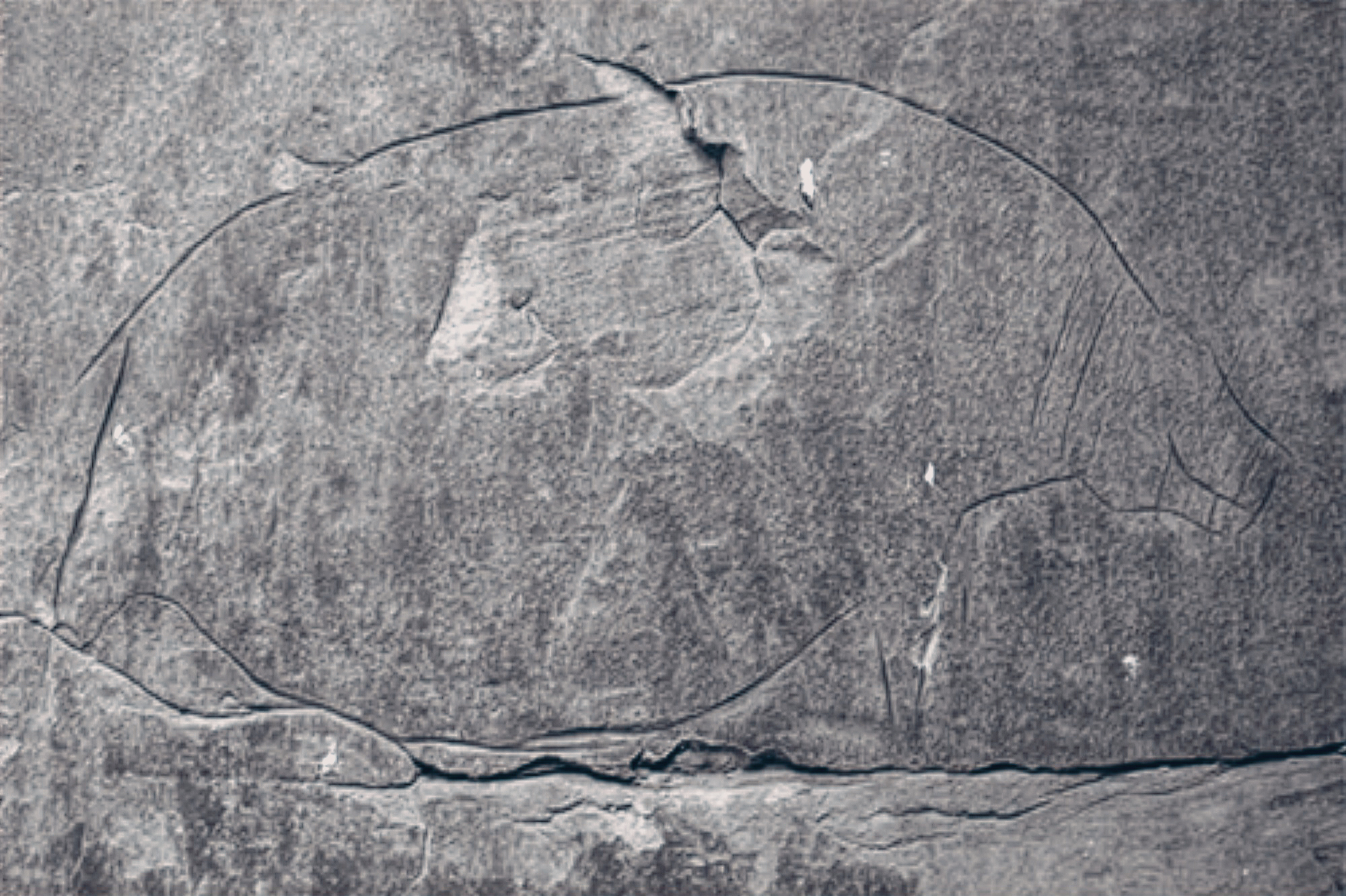

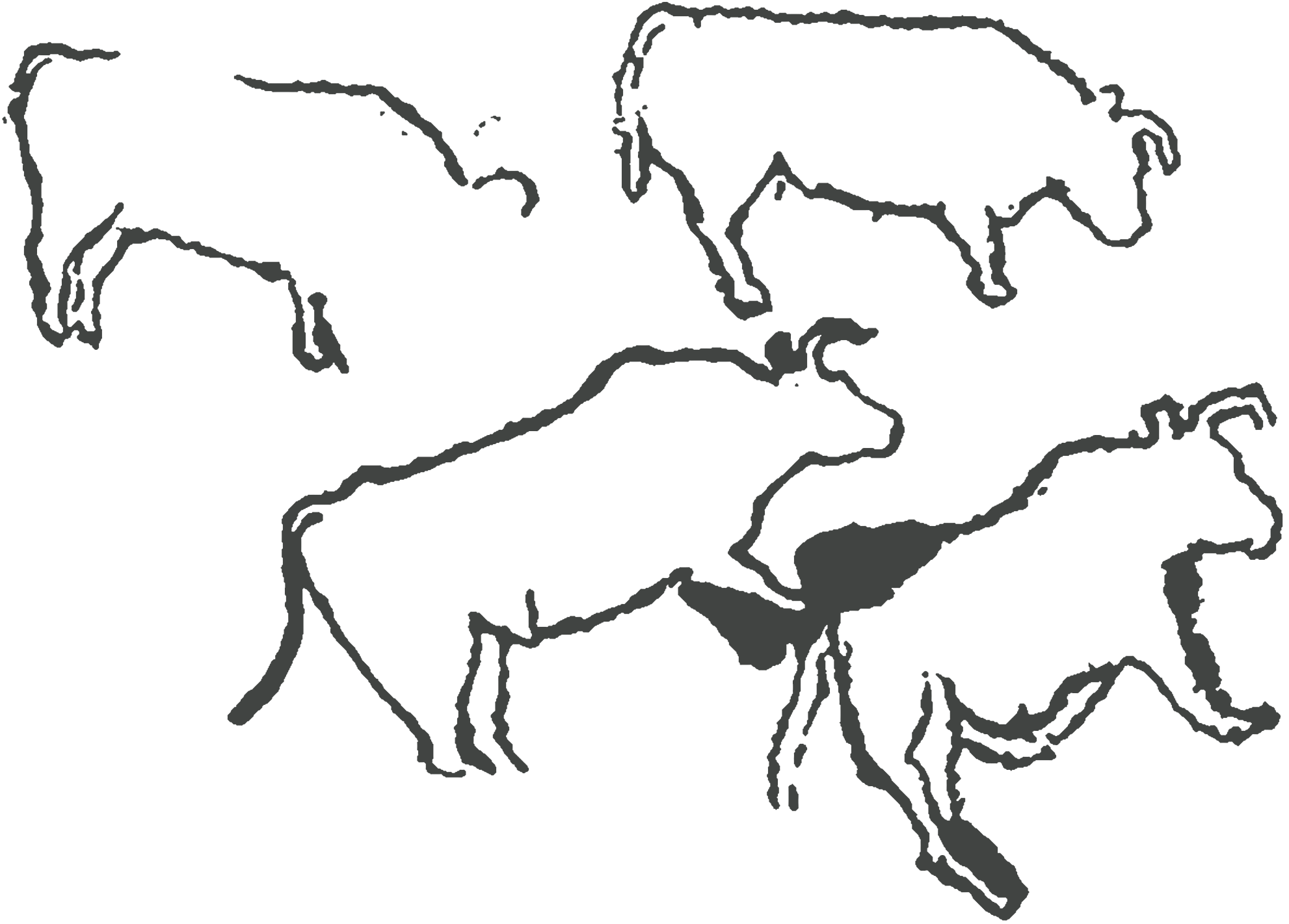

Late Palaeolithic naturalistic-style petroglyphs in Egypt are thus far known from two locations: at Abu Tanqura Bahari at el-Hosh (henceforth ATB11) and Qurta (see map below). At Qurta three sites have been localised bearing this type of rock art: QurtaI, II and III (henceforth QI, QII and QIII) (Figure 2, Figure 3). In all, slightly less than 200 drawings have been identified: about 35 at ATB11 and about 160 at Qurta. As the recording of the sites progresses, this number will definitely increase. Both at ATB11 and at Qurta, bovids are the major rock art theme (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6). These animals are undoubtedly aurochs or Bos primigenius. No less than 70 percent of the rock drawings represent this species. Other types of fauna include birds (at least 7 examples) (Figure 7), hippopotami (at least 3 examples), gazelle (at least 3 examples) (Figure 7), fish (2 examples) and donkey (1 example). In addition, there are also (at least) 9 stylised representations of human figures (mostly shown with pronounced buttocks, but no other bodily features) (Figure 8).

The ATB11 and Qurta rock art is quite unlike any rock art known elsewhere in Egypt. It is clearly substantially different from the ubiquitous ‘classical’ Predynastic rock art of the 4th millennium BC, known from hundreds of sites throughout the Nile Valley and the adjacent Eastern and Western deserts.

In a general way, this rock art bears the following main characteristics:

- As far as the spatial organisation of the art is concerned, there are no evident scenes (compositions displaying a narrative content). Compositions are limited to the juxtaposition of a few images (like two opposed bovids and a bird frieze composed of three drawings at QII). Figures seem rather to be conceived as individual images. In contrast to the rock art of the Predynastic period, there are no imaginary ground lines present. Images can be drawn in all possible directions (and quite often the head is represented upward or downward) (Figure 9);

- Quite often the animals are shown in dynamic poses, their backs curved and their legs bent as if in motion. In this respect they are also different from Predynastic images, which are mostly extremely static;

- From a technical point of view, both hammering and incision have been practised to create the images. In a considerable number of cases, both techniques have been combined to create or complete a drawing. Some of the figures are almost executed in bas-relief;

- The dimensions of the drawings are exceptional. Quite often the bovids are larger than 0.80m. The largest example even measures over 1.80m. In this respect the Qurta rock art is again quite unlike the rock art of the Predynastic period, in which animal figures are only exceptionally over 0.40-0.50m;

- Often natural features, such as the relief of the rock surface and/or fissures in the surface, have been integrated into images. One typical example of this is a large bovid at QII, where a (only slightly modified) natural vertical crack in the rock surface has been used to render/suggest the back part of the animal;

- Naturalistic images of animals are combined in this rock art with highly schematised human figures;

- Quite often the drawings are clearly deliberately left incomplete. Elaborately engraved bovids, for instance, lack front legs or are otherwise incomplete. In a number of cases animals (both bovids and hippopotami) show numerous scratches over the head and neck, which, evidently, must have some kind of symbolical meaning (Figure 10).

As regards style and a number of iconographical particularities, it should, however, be stated that this Late Palaeolithic rock art shows remarkable affinities with the Late Magdalenian rock art of Europe. This is particularly evident from the human figures, most of which are very similar to the anthropomorphs of the Lalinde-Gönnersdorf type (general discussion and distribution map in Lorblanchet & Welté 1987).

Moreover, some of the more elaborately executed bovids at Qurta are reminiscent of Late Magdalenian aurochs representations, such as those from the Grotte de la Mairie in Teyjat (Dordogne) (Barrière 1968). Both the Lalinde-Gönnersdorf type figures and the latter bovids are dated to the period of about 13,000- 12,000BP.The question whether or not the probable anteriority of the ATB11 and Qurta images to their European Late Magdalenian counterparts by several thousands of years has broader implications in terms of long-distance influence and intercultural contacts, is difficult to deal with on the basis of the current evidence.

The attribution of the ATB11 and Qurta rock art to the Late Palaeolithic has thus far provoked hardly any critical comments from the scientific community. One sceptic, Jean-Loïc Le Quellec (2007), has claimed that parallels for the Qurta rock art should rather be looked for in the Naturalistic Bubaline” style or school from the central Sahara and Libya, which he dates to the 6th and early 5th millennium BC. One glance at the latter, however [see, for instance, the article by Solheilhavoup (2007) in a previous issue of INORA], makes clear that the “Naturalistic Bubaline” school has absolutely nothing in common with the ATB11 and Qurta rock art. The “Naturalistic Bubaline” style, in fact, is not a naturalistic style at all, but rather a conventionalized caricature of nature. And, in contrast to what Le Quellec claims in his comment, the complete absence of large “Ethiopian” fauna (elephants, giraffe, and the like) is indeed an additional argument to date the rock art to the Late Palaeolithic. The latter animals, in fact, appear only later in the Egyptian natural environment, well after the onset of the Holocene, that is after about 12,000 BP. That is also the reason why they are abundantly represented in the much later “Naturalistic Bubaline” art of the Sahara.

Lastly, we owe a word of apology to our French colleagues for having “abused” the name of Lascaux with respect to the Qurta rock art (see the title of the Antiquity publication). It should be clear, however, that Lascaux has been used here as an icon (or rather THE icon) of Palaeolithic art. It was not our intention to state that Franco-Cantabrians were artistically active along the Nile or to claim that Lascaux was painted by “Egyptians”! Admittedly, the use of the word “Lascaux” has worked well in the media. Even though scientifically somewhat more correct, titling our contribution “Teyjat along the Nile”, would not, I presume, have aroused similar excitement. From a purely aesthetical point of view, Lascaux definitely remains unsurpassed. Scientifically speaking, however, the new find of a vast complex of open air Palaeolithic rock art in Egypt, a true Côa in Africa, opens as exciting avenues of thought as the discovery of that fabulous French cave almost seventy years ago.